By Lukas Fiala

It’s hard to go a day without reading about new economic security measures on either side of the Atlantic. From EU tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles to the U.S. Treasury’s sanctions on China’s dual-use trade with Russia, the past weeks have once more demonstrated that the global economic system built around institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) is fragmenting at an increasingly rapid pace.

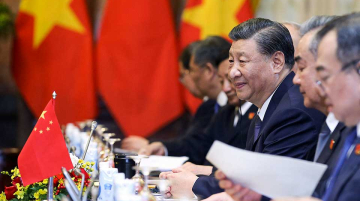

Earlier this week, the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) published a report by Max Zenglein and François Chimits focusing on China’s evolving strategy amidst this new geoeconomic reality. At the heart of the report lies the argument that as we shift away from decades of U.S.-led liberal-economic globalization, China’s “quest for global economic power” will deploy a different set of strategies, policies, and tools.

The authors identify three pillars of geoeconomics with Chinese characteristics: (1) the securitization of China’s domestic economy; (2) the expansion of economic influence across the Global South to offset worsening relations with the West; and (3) the use of potentially coercive economic leverage through the weaponization of access to choke points, China’s large domestic market and technology industrial base.

Because of the second pillar, analysts have long argued that the Global South might stand to win from economic competition between the U.S. and China. From an influx of financing for infrastructure to the re-shoring of certain supply chains away from China—such as some of Apple’s to India—bilateral competition is generally seen as widening developing countries’ policy spaces by making viable alternative partners available to them.

I don’t think this argument is wrong. It still holds in several cases, such as Saudi Arabia’s ability to benefit from Chinese technology cooperation or Angola’s bid to play off the U.S. and China in the race to access critical minerals to power the green transition.

However, thinking long-term, it’s worthwhile reflecting on what development strategies will succeed amidst global economic fragmentation. Over the past decades, countries that have outperformed their peers have mostly relied on export-oriented manufacturing to move up the value chain.

The bargain was relatively clear. From South Korea and Taiwan to Japan and Singapore, access to advanced Western markets, tech ecosystems, supply chains, and capital flows was exchanged for integration into the U.S.-led international economic order and underwritten by U.S. power, in many cases through close military partnerships or even alliances.

The Asian “developmental” or “tiger” states, as they would come to be known, were certainly no feat of liberal economic theory. While most have since democratized, rapid growth was the complex product of authoritarian economic and social management paired with a host of more context-dependent comparative advantages such as labor supply or strategic geographic locations.

One crucial element that enabled the transition towards export-oriented industrialization, however, was access to a relatively stable international trading environment and to leading economies such as the U.S. and Japan.

With our global economic order fragmenting and the WTO practically incapacitated, developing country governments will need to adjust to new geoeconomic realities when planning their economic strategy for the next decades. And as we look into an uncertain future, it is less clear than ever whether past success stories continue to offer clear guidance.

The current global economic governance system is certainly far from perfect. From botched debt restructuring to unequal trading relationships, developing countries have much reason to look for new opportunities in a system in transition. This period of economic fragmentation will create new challenges, however, and only the countries most adept at navigating them may one day emerge as the new group of “tigers”.

Lukas Fiala is the project head of China Foresight at LSEIDEAS.