By Lukas Fiala

When Ursula von der Leyen took on the top job in Brussels back in 2019, she vowed to transform the European Union’s quasi-government—the European Commission—into a “geopolitical Commission.”

Little did EU bureaucrats know just how quickly the trifecta of COVID-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the war in Gaza would usher in a new era for the EU’s role in international affairs.

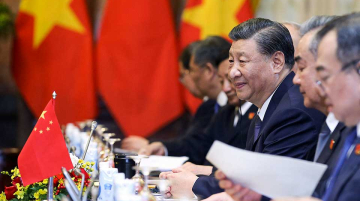

The bloc’s future relationship with China has been at the center of related policy discussions. From scrutinizing Chinese investment to attempts at rivaling Chinese infrastructure diplomacy across the Global South with the Global Gateway and the recently announced India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, having designated China a “systemic rival,” the Commission has over the past five years promoted a more assertive European position vis-à-vis Beijing.

Despite von der Leyen’s efforts, however, it remains unclear whether Europe genuinely understands how it wants to compete with China on economic, diplomatic and security issues.

And last week’s European Parliamentary elections have shown just how difficult it will be to bridge the deep divides among the European public when it comes to projecting the EU’s future role in international affairs.

Ahead of the poll, the elections were widely anticipated to strengthen Europe’s far-right, given issues such as high inflation and migration were prevalent across the continent. And yet, many were still surprised by just how much ground right-wing parties gained.

In the words of Politico: “Far-right parties dominated provisional results in the European Parliament election, triggering a snap election and a political crisis in Paris, and soul-searching in Berlin, where the ruling coalition was humiliated.”

Despite this result, it’s important not to overstate the importance of these outcomes for the EU’s future relationship with China. After all, the European Parliament is not the main foreign policy decision-making venue in the EU.

European foreign policy has long been dominated by the bloc’s largest countries—especially France and Germany—and their influence within both the European Council and Foreign Affairs Council.

Nevertheless, a Europe with a stronger reactionary far right will be less conducive to fostering joint decisions on key foreign policy and strategic issues. Strategic autonomy—the EU’s shorthand for a more independent European voice in the context of US-China competition—will be even harder to achieve with a bloc split between competing visions of Brussels’s future role in international and European affairs.

While it is likely that various Eurosceptic parties – from France’s Rassemblement National and Austria’s Freedom Party to the Hungarian Fidesz and the Alternative for Germany – will try to join forces in their pursuit of a more nationalistic, illiberal, and fragmented Europe, it is less clear whether they have solutions to Europe’s policy dilemmas in an age of great power competition.

For instance, the general emphasis on protecting national interests and European sovereignty – dubbed “fortress Europe” by the Austrian and German far-right – is hardly imaginable without a pan-European effort to strengthen Europe’s economic, diplomatic, and security role in the international system.

Indeed, a kind of inward-focused “Europe first” approach with various national manifestations would likely call into question the very idea of competing with China on issues such as infrastructure or trade.

In a world of two dominant great powers, it begs the question what response the far-right has to the obvious reality that only a more coordinated European economic, security, and foreign policy is capable of even trying to preserve Europe’s strategic sovereignty in this new era of geopolitics.

The irony of writing about EU elections from the vantage point of post-Brexit London is certainly not lost on me. But with French elections on the horizon and von der Leyen apparently set for a second term as Commission President, it seems less clear than ever whether Europe really knows how to compete with China across the Global South – or whether it is even willing or capable of doing so.

Lukas Fiala, Project Head of China Foresight LSE IDEAS.