By Felix Brender 王哲謙

Amid escalating conflicts across the Middle East since 2023, Beijing has been increasingly silent. Long eager to position itself as benevolent and neutral, China has offered little more than carefully worded statements while the region spirals. It is a performance in restraint — or perhaps reticence — that speaks volumes.

Just two years ago, Beijing had garnered praise for brokering (the final steps of) a surprising rapprochement between Riyadh and Tehran, a diplomatic coup some saw as heralding a new era of Chinese engagement. Beijing appeared eager to outshine Washington’s traditional dominance, presenting a model of “win-win” pragmatism over hard power or ideological imposition. Its continued purchase of Iranian oil — even under sanctions — suggested solidarity with Tehran, one of Beijing’s few supposed allies.

According to some analysts, Iran is also among China’s few ideological fellow travellers in anti-Western positioning — a strategic kinship in a landscape where most of Beijing’s relationships remain transactional or hedged. Carefully cultivating an image as a stabilizer, not a provocateur, China appealed to war-weary capitals across the Gulf and beyond.

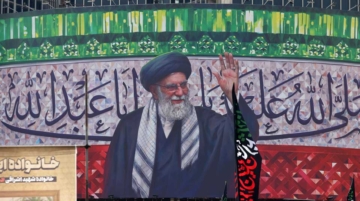

Yet, as tensions peaked between Iran and Israel — with direct strikes, retaliatory campaigns, and U.S. involvement — Beijing remained a study in caution. Apart from calls for de-escalation and UN communiqués, there was little sign of meaningful action as Israeli missiles shattered the Islamic Republic’s long-held nimbus of invincibility: The Islamic Republic, a self-styled bastion of “resistance,” now looked more like a paper tiger.

This exposure, in turn, laid bare the limits of China’s commitment. For all its investment in the optics of leadership, Beijing behaved more like a companion with commercial interests rather than a comrade. Iran’s moment of crisis found its supposed allies and friends—including China—absent.

Nor was Iran the first to discover these limits. Russia, too, has found China’s strategic friendship wanting. Since invading Ukraine, Moscow has received little more than calibrated trade and rhetoric about sovereignty and multipolarity. Despite the much-vaunted “no-limits” partnership, China has shown Moscow boundaries by only offering support when beneficial and at a manageable cost. For both Moscow and Tehran, the message is clear: China’s friendship holds in times of opportunity, not danger.

This may not be a quirk of China alone. Autocracies often struggle to rally around causes beyond regime survival. Without the universalist vocabulary liberal democracies deploy, authoritarian states tend to align in grievance, not vision — especially when action demands risk, coalition-building, or moral clarity.

To be fair, China’s caution is not without rationale. Tangling with the U.S. military or jeopardizing energy flows through the Strait of Hormuz carries risks far beyond the theatre of regional politics. And perhaps, in this restraint, there is method. For all its talk of multipolarity and principled neutrality, Beijing may well recognise that the region offers no good outcomes — only volatile partners with diminishing returns.

The art of war, Sun Tzu reminds us, lies not in bold declarations but in quiet understanding: 知彼知己,百戰不殆. China may well act cautiously because it sees the field clearly. But inaction may be what limits its ascent. For all its reach, Beijing still opts for safety, not responsibility. Yet the hallmark of true global leadership is not merely caution but the willingness to bear costs, absorb risk, and at times, subordinate interest to influence.

China’s MENA moment may not be over, but it is undeniably fading. Without the will — or means — to do more than watch, Beijing risks becoming not the alternative to the West it imagines, but that others increasingly stop counting on it altogether.

Felix Brender is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics.