By Saniya Kulkarni

There has been much scrutiny of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit two weeks ago – especially around the fact that it was entirely virtual. Compelling arguments have been put forth on both sides, the advantages and disadvantages of a virtual summit have been debated, and despite this, the official reason for India as a host doing so remains unknown.

It is likely that India’s diplomatic calendar might have been too busy to host another high-profile meeting just three months before the G20 Summit, but it could also be the case that fundamental differences between China and Pakistan on regional matters discussed at the SCO were a motivating factor to avoid exacerbating disagreements.

India has certainly tiptoed around and even rejected several SCO initiatives. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s address at the summit this year contained an unsubtle reference to Pakistan employing ‘cross-border terrorism’. But its main point of contention with the discussions at the organization is the tacit support for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which India finds difficult to digest due to its incompatibility with India’s claim over Kashmir.

This is also evidenced by the initiatives that India has brought to the SCO table, including the theme of this year’s Summit, ‘SECURE’, which stands for security, economy and trade, connectivity, unity, respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, and environment. India’s territorial integrity has been front and center in this initiative, as well as others it has raised.

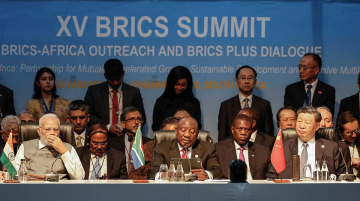

Some argue India has constrained the SCO agenda, whose purpose had already been broadened over the years since its conception as a Sino-Russian security organization. It has also been pointed out that the SCO is struggling to find a common purpose and is another victim of the trouble India and China have with any degree of cooperation – reminding one of a similar argument with regard to BRICS.

Indeed, even within the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorism Structure (RATS), cooperation is not a given as New Delhi still continues to accuse Pakistan of instrumentalizing links with terrorist networks in the region, especially in Kashmir. Ultimately, India has rarely taken on leadership positions and agency in multilateral settings in the past.

What matters most at the moment is the evolving India-China relationship in the context of the upcoming G20 Summit in September. At the beginning of this year, we outlined ways in which the India-China relationship has a rocky road ahead, and seven months in, rocky it has been, to say the least. The upcoming summit will be a key milestone to evaluate how Beijing and New Delhi perceive each other’s claims to leadership in the Global South.

Reports suggest that China has anxiety over being absent from India’s recent meeting of Global South leaders as part of its G20 presidency, and therefore being excluded from the Global South as a whole. The months leading up to the G20 summit will tell us more about what we can expect from the bilateral rivalry, and how the two manage it is likely to determine the success of Chinese-led multilateral organizations like the SCO and BRICS.

Saniya Kulkarni is a project coordinator at LSE IDEAS.