When the U.S. Prohibition Act (1920–1933) banned alcohol, it unexpectedly turned Cuba into a vice paradise—and reshaped the destiny of Chinese migrants fleeing America’s anti-Chinese racism.

As thirsty Americans flooded Havana’s bars and casinos, the island’s economy boomed. Meanwhile, the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882–1943) had already pushed thousands of Chinese laborers out of the U.S., with many rerouting to Cuba. Others, like Gao Zhaotang (Ramón), came directly from Guangdong, lured by tales of Havana’s “golden streets”—where Chinese-run restaurants, laundries, and shops thrived under American tourist dollars.

Yet this forgotten migration corridor—between U.S. exclusion and Cuban opportunity—has faded from public memory. A fieldwork done by a Chinese scholar called Tang Yongyan reconstructs one such life, revealing how geopolitics, vice economies, and the Cold War ruptures stranded migrants like Gao between worlds.

Here is the summary of her fieldwork diary published on the WeChat official account of Tsinghua University Institute of International and Area Studie:

Gao’s fragmented history emerged through the oral accounts of Carmen, a Cuban-born Chinese descendant, alongside yellowed letters, scattered artifacts, and archival traces.

His story reflects the broader Chinese-Cuban experience—shaped by indenture, revolution, Cold War politics, and the painful erosion of transnational family bonds.

Migration: Dreams and Displacement

In 1919, 22-year-old Gao left Zhongshan, lured by tales of Cuba’s prosperity during the U.S. Prohibition Era (1920–1933), when Havana became a playground for American vice tourism. Unlike Chinese migrants barred from the U.S. by the Chinese Exclusion Act, those in Cuba built thriving communities. Gao toiled in vegetable shops and restaurants, sending meager earnings home—a lifeline for his family during China’s turbulent warlord era.

Yet after 1966, the letters and remittances stopped. As Sino-Cuban relations soured, communications were cut off, leaving families like Gao’s in silence.

The “Little Father” Without a Family

Gao never married—a common fate among Chinese migrants who postponed returning to China to start families, only to be stranded by history. In Havana, he became a surrogate father to Carmen, whose biological father, a reserved shopkeeper, emotionally detached from his Cuban life while clinging to Chinese traditions.

But his dream of returning to China collapsed in 1966. Scheduled to board a repatriation ship, Gao fell ill with a hernia. Surgery failed, and he died alone in his apartment.

A Grave Robbed, a Spirit Unrested

Gao was buried in Havana’s Chinese cemetery, but his remains were later desecrated by practitioners of Santería, an Afro-Cuban religion that mythologized Chinese bones as potent ritual objects. In 2018, Carmen salvaged his scattered bones, placing them in an urn at her home altar.

Reconnecting the Fragments

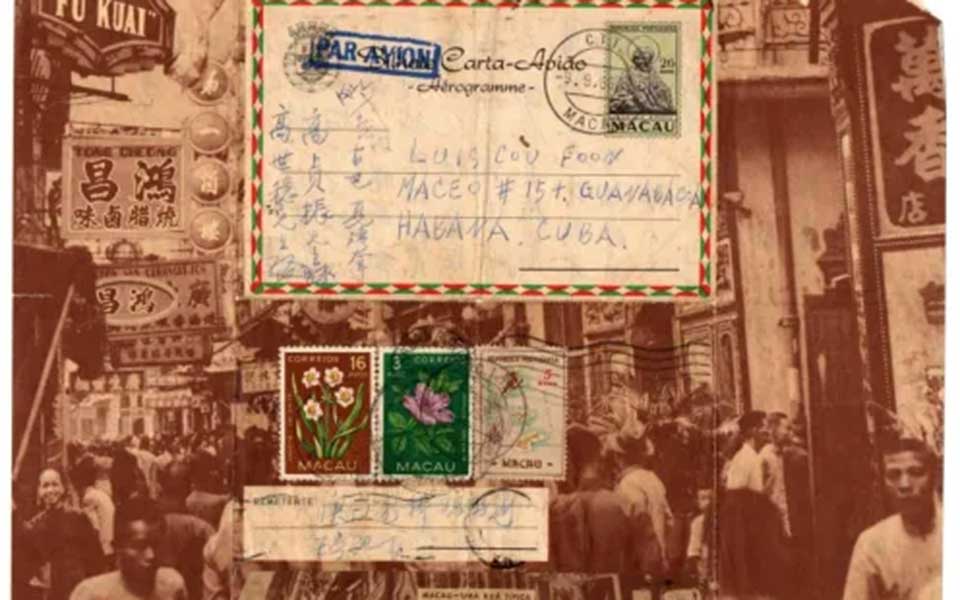

In 2019, Carmen discovered Gao’s old letters to Zhongshan and mailed them to his relatives—but the package gathered dust for years. It wasn’t until 2024 that his nephew, Lin Shaoliang, learned of the letter and reignited the search.

Through translated emails and a tearful video call, Carmen and Lin’s family bridged six decades of separation. Lin finally learned the truth: his uncle had died waiting to come home.