A rural Chinese farmer paid over 200,000 yuan (around $28,000) to join a marriage tour in Vietnam—three months later, his new wife vanished.

This is not a rare case: stories like his have circulated on Chinese social media for over a decade, but a new investigation by The Beijing News reveals the cross-border marriage industry is operating at massive scale in a legal grey zone.

Searching “Vietnamese blind date” on China’s court verdict database, The Beijing News reporters found 189 relevant rulings since 2014: 35 cases involved organizers convicted of smuggling people across borders, 6 for fraudulently obtaining travel documents, 6 for scams, and 19 for disputes over unjust enrichment.

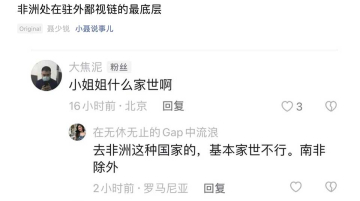

The Douyin-Fueled Fantasy of a Foreign Wife

The phenomenon gained momentum after China lifted its strict “Zero-COVID” policy in late 2022. During the pandemic, millions of rural men became increasingly active on social media, especially on Douyin (China’s TikTok), where they encountered a wave of influencer content glamorizing life with Vietnamese or Laotian wives. Influencers like Wu Xiaoming and his Vietnamese wife Li Shiyue posted seemingly idyllic domestic videos—feeding the dream of a better, more affectionate marriage outside China’s tightening marriage market.

Zhang Zhengzhou, like many others, was drawn into this fantasy. After spending thousands on gifts and livestream donations, he joined one of Wu’s “marriage tours” to Vietnam, where he and three other Chinese men met and soon married local women. But within months, three of the brides had fled. The tour organizer couple, Wu and Li, were later arrested by Chinese authorities and charged with “organizing others to illegally cross national borders,” a criminal offense under Chinese law.

Legal Blind Spots and Regulatory Gaps

This article is significant not only because it documents a rising social trend, but also because it dissects the legal blind spots surrounding cross-border matchmaking in China. Despite a 1994 State Council regulation prohibiting individuals from engaging in profit-driven or deceptive foreign marriage matchmaking, enforcement remains ambiguous. Legal experts quoted in the article argue that if Wu and Li merely facilitated introductions and translation, their actions might warrant administrative penalties, not criminal charges. However, by helping individuals obtain travel visas under false pretenses and coaching them to lie to customs officials, their actions crossed into criminal territory.

A Desperate Demand

The story taps into a broader social issue: the mounting pressure faced by rural Chinese men in a gender-imbalanced society where traditional marriage is seen as a vital milestone. With urbanization, women in rural areas increasingly migrate to cities, leaving behind a pool of men who struggle to find partners. The allure of a submissive, caring foreign wife—heavily romanticized by Douyin influencers—has led to a booming but legally dubious cottage industry.