Observers of China-India relations had a busy fourth quarter last year. In late October 2024, the two states announced the conclusion of a border patrol agreement, signaling a thaw in border tensions that had persisted for more than four years. A flurry of high‑level meetings followed the accord, where top leaders worked on putting Sino‑Indian ties back on track. Nevertheless, the pact and the subsequent engagements are precursors to incremental improvements rather than a radical turnaround in bilateral relations.

Sino-Indian relations have been strained since a bloody confrontation on their disputed border in 2020. After the deadly Galwan Valley clash in June 2020, the two sides deployed additional troops in the vicinity of the disputed areas, raising the chances of escalation. The conflict spilled over to other areas of Sino-Indian ties as well. Chinese businesses struggled in India due to app bans, tax raids, and rejected investment projects. At the same time, Chinese journalists failed to secure visas in India and vice versa.

The October agreement ended the prolonged standoff between the two sides. The accord allows the two sides to revert to pre-2020 patrolling practices in disputed areas and reduce frictions on the border.

While public insight into the border patrol agreement is limited, a targeted scrutiny of actions on the border and the subsequent high-level meetings reveals quite a few things about the trajectory of Sino-Indian relations in 2025.

On the border, troops disengaged from the areas of Depsang and Demchok by the end of October 2021. These were areas where tensions between Chinese and Indian soldiers were the highest after 2020. The disengagement was confirmed by verification patrols, and the two sides subsequently agreed to conduct coordinated patrols on a weekly basis. In late December, both Defence Ministries confirmed the progress and stability on the border.

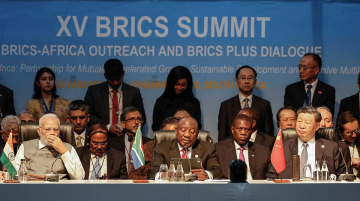

There was advancement on the political level of China-India relations as well. Two days after the announcement of the border patrol agreement, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia. The Xi-Modi gathering laid the foundation for subsequent meetings between foreign ministers, defense ministers, and special representatives on the boundary question. The process culminated in a 6-point consensus between the two sides. In simple terms, the consensus doubles down on the importance of border stability and cooperative Sino-Indian relations.

Going into 2025, we can expect further stabilizing efforts on the border. Disengagement put some distance between the troops in Depsang and Demchok, but it is only the beginning of the de-escalation process. A potential result on this front is the long-term reduction of troops and equipment on the border. Successful de-escalation could prompt new confidence-building measures, further stabilizing the boundary. These steps could help China and India achieve the “strategic trust” that was often mentioned during the recent high-level meetings.

2025 is likely to be a year of cautious progress in Sino-Indian relations, providing an opportunity for external actors to adapt their Asia policy and make the most of the developments.

The success of building this strategic trust is going to be a key determinant of broader China-India relations. With a stable and peaceful China-India border, the most likely scenario is the incremental normalization of the bilateral relationship. Such a process is most likely to start from less sensitive issues and proceed to more complex ones. The high-level political exchanges after the border patrol agreement referred to the restoration of the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra pilgrimage, direct flights between the two countries, and media ties.

Encouraging developments in cultural interactions, media contacts and air travel could pave the way for strengthening economic relations. This scenario would benefit both sides, as China could capitalize on India’s 1.2 billion strong market, while India could rely on China in the pursuit of becoming a manufacturing hub.

Of course, the incremental improvement of Sino-Indian ties is not immune to sporadic setbacks. On 25 December, the Chinese government authorized the construction of the world’s biggest dam on the Yarlung Zangbo, a river that starts from China’s Tibet Autonomous Region and flows to India and Bangladesh. Although China states that the dam will not significantly impact the environment or the water supply of downstream states, New Delhi lodged a protest to Beijing to convey its concerns.

Two days after the approval of the dam, China established two new counties, He’an and Hekang. According to the Chinese announcement, these new administrative units are in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region. The Indian side, however, claims that He’an and Hekang “include parts of the union territory of Ladakh.” Once more, India protested the measure.

Occasional problems aside, China-India relations are likely to improve in 2025. This has implications for external actors. The US is losing leverage in the Indo-Pacific. Stable China‑India relations reduce India’s strategic reliance on the US and make New Delhi less inclined to be a “bulwark against China.”

Russia benefits from the developments. It can maintain steady trade ties with China and India, two states that keep engaging with Moscow, regardless of its international economic isolation. The border deal neutralizes the possibility of a potential China‑India conflict that could have damaged this precarious balance and, by extension, Russia’s economic lifeline.

Similarly, the EU could tap into both the Chinese and Indian markets, which are undisturbed by the potential of a border conflict for now. This could be vital economic support for Brussels against potential punitive tariffs under the second Trump administration.

Long story short, 2025 is likely to be a year of cautious progress in Sino-Indian relations, providing an opportunity for external actors to adapt their Asia policy and make the most of the developments.

Daniel Balazs is a Research Fellow of the China Program at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.