By Lukas Fiala

U.S. President Donald Trump’s page turner of a speech at the UN General Assembly this week was many things, but certainly no homage to the United Nations. Exhibiting the president’s well-known skepticism of multilateralism and rejection of globalism, Washington once more demonstrated that it really doesn’t want to lead the world it was so involved in building eighty years ago. What Trump’s performance made clearer than anything, however, is that the UN is currently positioned between competing visions for global order between the U.S. and China.

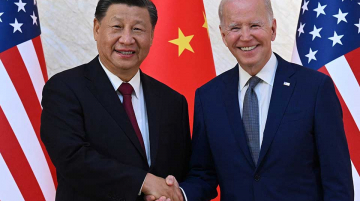

Indeed, on paper, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s and Trump’s discourse about the UN could hardly be more different. Stating that “not only is the UN not solving the problems it should, too often it’s actually creating new problems for us to solve”, Trump made clear that the UN is not a priority within US foreign policy, following the White House’s emphasis on championing sovereignty and rejecting globalism.

Just three weeks ago, during his speech at the SCO summit in Tianjin, Xi stated contrastingly “[w]e should firmly safeguard the status and authority of the U.N., and ensure its irreplaceable, key role in global governance.” For Trump, the UN is little more than a symbol of globalist overreach, a talk-shop with limited utility in solving real global problems. For Xi, the UN is the centrepiece of China’s strategy to refashion the international system in China’s image while projecting a more confident Chinese voice into international organisations and institutions.

It may be obvious but criticizing the UN at a time of global disruption, from non-proliferation to artificial intelligence and the climate crisis, will only play into the hands of Beijing.

Over the past decade, China has invested significant resources into shaping contemporary multilateralism and the UN at its core according to its own interests. This has led to an incremental increase in China’s influence within the multilateral organization, as reflected in various indicators, including personnel appointments and growing budgetary responsibilities.

Beijing’s approach has been multi-dimensional, from taking on a larger role in UN peacekeeping missions to placing Chinese officials into important portfolios within the organization – such as the FAO and UNIDO. China has also become more targeted in promoting its own foreign policy discourse on issues of key concern – such as Russia’s war in Ukraine or human rights issues. Not all these tactics have always been equally successful, but it is likely that China is perceiving the present moment as a key opportunity to expand on these earlier efforts to benefit from US withdrawal.

As I mentioned last week, great powers ultimately tend to have a selective approach to international commitments, rules and norms. Whether we like it or not, both Beijing and Washington have at times failed to live up to their multilateral obligations. From UNCLOS – which the US has not ratified and China conveniently ignores in its grey zone operations across the South China Sea – to the Arms Trade Treaty – which China has signed but the U.S. has also failed to ratify – abundance in national power affords both Washington and Beijing a degree of exceptionalism in engaging with the UN and international law at large.

However, for Washington at least, this should not be an excuse to turn away from the UN as a key pillar of international order. Doing so will only exacerbate existing deficits in global governance while handing a carte blanche to a rival great power with a very strong interest and – increasingly – capability to reshape the organisation from the inside. Amidst renewed great power competition eighty years after its founding, the UN may well be facing its greatest challenge yet.

Lukas Fiala is the project head of China Foresight at LSEIDEAS.