By Saniya Kulkarni & Lukas Fiala

The world’s largest democracy has gone to the polls. And while Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lost their outright majority, the incumbent Prime Minister resigned on Wednesday to pave the way for a dissolution of parliament and the formation of India’s next government.

With Modi poised to take on a third term as the leader of the world’s most populous country, where will China feature in India’s foreign policy priorities?

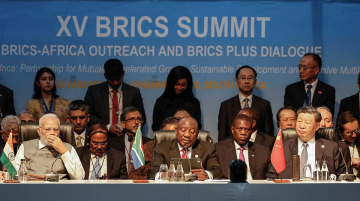

Indian foreign policy in the more recent Modi years can be summarised as that of projection. India has continued vying for a greater leadership role in the Global South through its promotion of ‘South-South cooperation,’ a key theme under its presidency of the G20 in 2023.

What is of note, however, is New Delhi’s consistent push towards more autonomy within its region and beyond. It is trying to assert itself as a more independent pole in a multipolar world while breaking away from the mold Washington very often expected India to act within.

The India-China bilateral relationship suffered a hit following the Galwan Valley clash in 2020, which resulted in the death of over 20 Indian and 4 Chinese troops. Nearly four years on, there have been efforts to normalize relations between the two, but these have been strained by repeated border skirmishes.

Dialogue continued on a limited level, usually restricted to multilateral summits. However, the Chinese Ambassadorial post to India remained vacant for 18 months until May 2024, the longest since 1976.

An enduring thorn in India’s side continues to be Beijing’s close military and defense relationship with Pakistan. Dubbed a “threshold alliance” by some analysts, China has fostered even closer economic, diplomatic, and military alignment with Islamabad under Xi Jinping.

From the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to more ambitious and long-term defense export programs, Beijing and Islamabad are pursuing their shared regional interest in containing India’s strategic space across South Asia with increasing confidence.

From China’s longest-running defense offset program with Pakistan, the JF-17 fighter jet, to Pakistan’s acquisition of Type 054A frigates, J-10C fighters, HQ-9/P missile defense systems, and VT-4 tanks, bilateral defense engagement between China and Pakistan strengthened during Modi’s second term.

Looking ahead, Modi’s third term will very likely continue its foreign policy goals of seeking greater strategic autonomy, furthering cooperation within the Global South, and strengthening India’s image as a great power.

Although unlikely, it will be interesting to see if there will be a shift in these goals considering this is the first time Modi will be leading a coalition government since he came to power in 2014. Negotiations for cabinet posts are currently underway in the Indian capital, but it is difficult to imagine the BJP would part from core ministries such as Home, defense, finance, and external affairs, among others.

Importantly, India’s international stature has become a staple in domestic discussions, and also a key issue in electoral politics. One key change of the Modi years has been the dismissal of the idea that foreign affairs fall only within the remit of elite debates. For instance, the increased presence of the Indian public as stakeholders in the country’s foreign relations became evident over the recent Maldives ordeal.

It is yet to be seen how this phenomenon will play out in other avenues of India’s foreign policy, but it is certain that the Indian people have been paying more attention to India’s role in the world.

With India keen to represent an independent voice across the Global South in the context of strategic competition between the US and China, we should certainly do so as well.

Saniya Kulkarni is a program manager at LSE IDEAS, and Lukas Fiala is the Project Head of China Foresight LSE IDEAS