By Rodrigo Rodríguez

On 26 January, a diplomatic spat erupted between Colombia and the United States, as the South American country’s president, Gustavo Petro, refused to land a flight carrying Colombian citizens deported from the US. Taking to social media, Petro said that the U.S. must “establish a protocol for the dignified treatment of migrants before we receive them”, suggesting that those on board had been treated like criminals.

Petro’s statement led to a harsh response from the U.S., which halted visa application processes in Colombia and threatened stiff tariffs on the country’s exports. A day later, Petro relented, accepting the deportation flights to avoid 25% tariffs, signalling what could be growing tensions between the two countries during U.S. President Donald Trump’s second term. The US is Colombia’s main trading partner, making any trade threat from the U.S. a potential headache for the country’s economy.

Some experts and members of the political opposition strongly criticized Petro’s handling of the situation. Some have called his actions “irresponsible” and “putting Colombia’s stability in jeopardy” or described his handling of the situation as “miscalculated.”

Amid this volatility, questions have arisen over the direction of the two countries’ relations, including whether Colombia must diversify its trade partners and reduce its dependence on the U.S.—most notably, in regard to China, which is a potentially closer ally in trade, investment, energy, and other areas.

Colombia and China relations

Although Colombia and China recently celebrated the 45th anniversary of diplomatic relations on 7 February, it was not until the 21st century that the latter rose to become one of Colombia’s most important trade partners, especially since the administration of Juan Manuel Santos (2010–2018). According to the Embassy of Colombia in China, as of 2023, China is Colombia’s second largest export partner, and its leading source of imports.

“Already, a decade ago, China was an important trading partner for many countries in the region, but since then, the relationship with Colombia has deepened,” said David Castrillón Kerrigan, a professor at the Externado University of Colombia, whose research focuses on Chinese and US foreign policies, and their impact on Latin America.

In 2008, in the midst of the global economic crisis, Colombia exported just over $400 million in goods to China, according to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE). This increased to more than $2.3 billion in 2024, and between January to August that year, Colombian exports to China had grown by 14.8% compared to the same period in 2023.

For its part, Colombia imported more than $14.7 billion worth of goods from China in 2024. A wide variety of Chinese goods enter the country, ranging from electronics and tyres to chemicals and textile products, according to data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC).

Still, Daniel Gómez, vice president of the Private Competitiveness Council, an organisation focused on strengthening Colombian business globally, believes that China is a market that has not been properly explored. “We have not been able to take advantage of the enormous demand coming from the Chinese market,” he told Dialogue Earth. Gómez points out that while Colombia has expanded its global trade network with nearly 20 free trade agreements with key players, its projection into the Asian market “has been more timid”.

China has made inroads into Colombia not only with products, but also via investment in infrastructure projects. Zhu Jingyang, China’s ambassador to Colombia, noted that over 110 Chinese companies currently operate in Colombia within the infrastructure sector, energy and mining, renewable energies, telecommunications, and health. The Colombian Embassy in China reports that 62 Chinese projects have jointly invested over $800 million in areas including infrastructure and energy. Notable companies that have invested include the China Harbour Engineering Company, which is leading a consortium of companies to build the first line of the Bogotá metro; Zijin Continental Gold, which owns the troubled Buriticá gold mine; and Trina Solar, which built the Bosque de los Llanos solar farm.

Some of these projects have brought challenges, particularly for those with complex environmental and social contexts, explains Julie Radomski, a Global China research fellow at Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center. “Over time, some projects ended up being problematic, in terms of their ramifications,” Radomski told Dialogue Earth. This has been the case in Bogotá, where construction of the metro is said to have impacted the environment and daily life for the city’s inhabitants, and payments for which have been the cause of a dispute between the mayor’s office and the presidency; and in Buriticá, where there have been attacks by armed groups.

The Geopolitics of the Belt and Road

In recent months, signals from senior Colombian officials have suggested that Colombia will soon be the latest nation to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – the umbrella under which China has expanded its global presence in investment and infrastructure projects.

In October 2024, Colombia’s then vice-minister of foreign affairs, Jorge Rojas Rodríguez, said that his country will join the BRI after further negotiations and discussion of both countries’ needs and priorities. Though no formal details have emerged since, speculation suggested that President Petro would make an announcement this month, but was forced to cancel amid a cabinet crisis.

Since 2013, nearly 150 countries have signed up to the BRI, with total funding committed through it passing $1 trillion as of 2023. To date, 21 Latin American and Caribbean countries, including Peru, Chile and Argentina, have joined the Chinese initiative, which has often heralded the arrival of grand Chinese-backed projects in infrastructure and the energy sector, though the focus has begun to shift towards smaller investments in recent years.

As the BRI has grown, bringing changing investment patterns and deepening countries’ trade relations with China, it has in many ways redefined geopolitics in the Global South.

Radomski described the BRI as “an umbrella term” that has grown beyond its original focus on connectivity, and is “a shifting term that encompasses the expansion of infrastructure and the expansion of China as a power.”

At a time of tension with the U.S., Colombia signing a memorandum of understanding with China on the BRI may not only represent a new alliance on trade and investment, but would also be a diplomatic move with strong implications. Radomski notes that while joining the BRI is mainly symbolic, “the geostrategic implications of joining the initiative are significant”.

This is not lost on the U.S. According to Margaret Myers, managing director of the Institute for America, China, and the Future of Global Affairs, part of the reason each Colombian government has moved tentatively towards a stronger relationship with Beijing is due to the country’s long-established close relationship with the U.S.

Moreover, in the U.S., the new administration has been vocal in its animosity towards China on trade matters. This manifested itself in the form of the tariffs promised by Trump in his presidential campaign, which have become reality for some countries and which may expand in the following months in industries such as automobiles, electronics, and pharmaceuticals.

“This is an administration [in the U.S.] that sees China as a threat,” Castrillón Kerrigan said. “If Colombia enters the [BRI] right at the start of the administration, it’s not going to be well received.”

He also pointed out that the interdependence between Colombia and the U.S. cannot be ignored—not only on trade issues but also in areas such as migration management: “Trump will surely punish Colombia.”

Independent of the Colombia-China relationship, it is possible that Trump’s agenda will lead to more tensions in other matters, such as aid and development. For example, in late January, the U.S. president ordered a 90-day suspension of all aid programs to foreign nations. In 2023 alone, Colombia received more than $738 million in assistance from the U.S. government for food, military and even migration-related programmes.

What Colombia Stands to Gain

The Private Competitiveness Council’s Gómez believes that Colombia’s entry into the BRI is an opportunity to strengthen ties with a market that is full of potential. “China is a market that is growing and will have significant demands for food, animal protein, or energy,” he says.

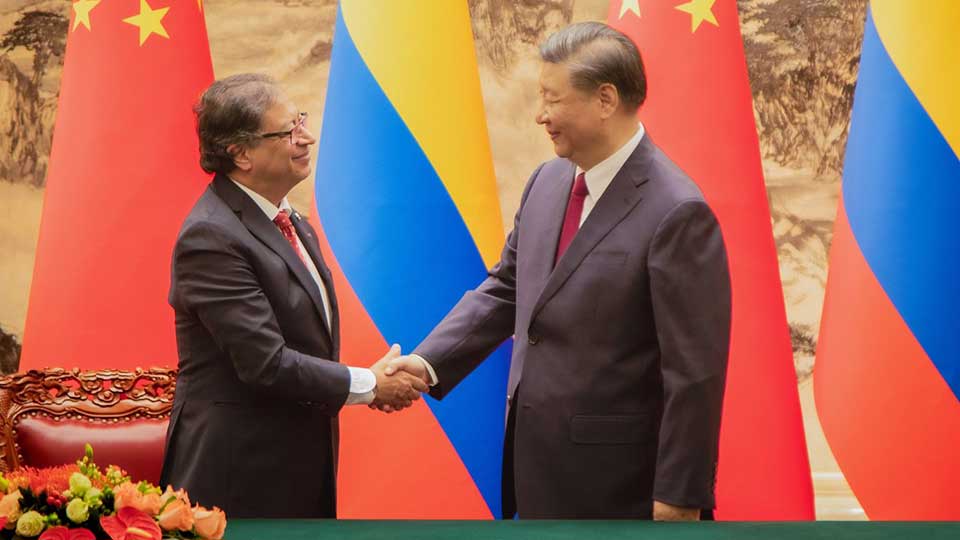

Castrillón Kerrigan agrees, noting that in recent years China has had a strong policy of increasing imports from the Global South to reduce its dependence on the United States and Europe. The agreements signed between Petro and Chinese President Xi Jinping during their 2023 meeting in Beijing described agriculture, renewable energy, manufacturing, and science among the some industries and sectors in which both countries seek to strengthen their ties.

The Petro administration’s focus on the energy transition and commitment to expanding renewable energy will be key to the dynamics between the two countries. Colombia’s environmental agenda synchronises with a China that is increasingly focusing on renewable energy in foreign infrastructure projects.

Today, China is the leading producer and exporter of solar panels. Castrillón Kerrigan and Radomski believe that there is currently no country with better infrastructure to assist in Colombia’s energy transition. “In terms of renewable [energy], it’s hard to think of other countries that are in the same league as Chinese companies,” Radomski said.

In 2023, nearly 43% of Colombia’s exports to China were of crude oil, in addition to charcoal briquettes at over 18%, according to OEC figures. Having China as a partner in the development of renewable energy sources, as well as having its support in the midst of the current administration’s plan for a just energy transition, could be crucial in supporting Colombia’s pivot towards other export products for the Chinese market.

Experts say another area in which Colombia could benefit is the modernisation of its agricultural sector. This has been a goal of President Petro, and an area in which China has a great amount of technical knowledge and infrastructure. “Colombia has seen China’s experience in eliminating extreme poverty in its country and improving conditions in the countryside through technification, and wants to replicate that,” says Castrillón Kerrigan.

Other potential cooperations include the relocation of Chinese manufacturing operations to Colombia—which Gómez suggests is a possibility within BRI negotiations—and the transport infrastructure projects that the Colombian government pitched to Chinese firms during Petro’s visit to Beijing.

Rodrigo Rodríguez is a Colombian journalist and podcast producer whose work has appeared in El Tiempo, Bocas, BBC, Sillon Studios and Revista Donjuan, where he specialised in environmental and scientific issues. He has also been an ICFJ Fellow. He tweets at @ElPrincipote.

This article was originally published on Dialogue Earth under the Creative Commons BY NC ND licence.