By Felix Brender 王哲謙

In the latest vignette of maritime theater off Yemen’s coast, a Chinese frigate decided to dazzle a German surveillance plane with a military-grade laser, forcing it to turn tail and return to Djibouti. Berlin is rightly incensed. Beijing’s antics risk the lives of EU personnel protecting Red Sea shipping, a lifeline of global commerce from which China itself profits. The episode underscores why the Bab-el-Mandeb (“Gate of Tears”)—the chokepoint between the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa—is rather aptly named in more senses than one.

Notably, this is not Beijing’s first such interference.

In 2018, for instance, the Pentagon accused Chinese personnel based in Djibouti of using military-grade lasers against U.S. pilots landing at the nearby U.S.-operated Lemonnier base, causing minor eye injuries in what was described as deliberate harassment of Western operations. The incident was quietly buried under diplomatic denials, but the emerging pattern is unmistakable: China is increasingly willing to inflict low-level disruption, particularly and including in the Red Sea.

China, like the Company in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, proclaims neutrality while deftly ensuring its interests are safeguarded. Its entanglement with Yemen’s Houthis exemplifies this method.

China’s goal is neither regional dominance nor outright subversion, but rather to keep the prevailing system sufficiently fragile to serve its interests.

Beijing maintains diplomatic channels with the Houthi-controlled Supreme Political Council, while providing indirect support—components for drones, satellite imagery, and signals of tacit tolerance that enable the Houthis’ disruptions. This is not about ideological kinship, but pragmatic utility: shielding Chinese interests while destabilizing the maritime operations of others.

The balance is delicate: enough support to matter, but never enough to earn the label of sponsor.

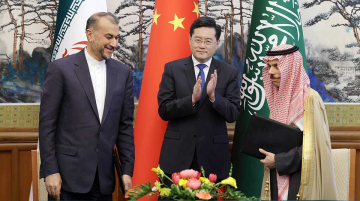

Equally telling is China’s careful alignment with Iran. Tehran, a strategic supplier of oil to China and a Belt and Road partner, benefits from Houthi agitation in the Red Sea. China’s engagement with the Houthis complements Iran’s regional ambitions, strengthening the Beijing-Tehran axis without requiring direct Chinese fingerprints on missiles launched towards shipping lanes.

Meanwhile, every Houthi drone or missile that entangles the United States in Red Sea security dilemmas benefits Beijing, while allowing China to position itself as the calm, alternative partner in a region plagued by Western ‘disorder’.

Yet China treads carefully. Openly embracing the Houthis risks alienating Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, jeopardising its Gulf relationships, and undermining its image as a neutral economic actor. Beijing’s strategy remains subtle: encouraging limited instability that weakens others while preserving plausible deniability.

It is not seeking to build a rival order, but to ensure that the existing one remains—or becomes—too brittle to constrain its ambitions. In the fog of Red Sea skirmishes and Houthi posturing, China does not simply find comfort in disorder—calculated disruption itself is Beijing’s strategy.

China’s actions are neither driven purely by trade interests nor part of a grand plan to replace the current order. Its goal is neither regional dominance nor outright subversion, but rather to keep the prevailing system sufficiently fragile to serve its interests, while avoiding the burdens of overt leadership.

Felix Brender is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics.