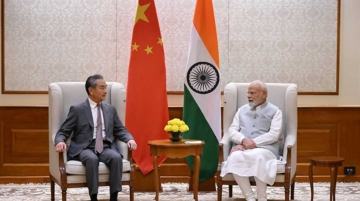

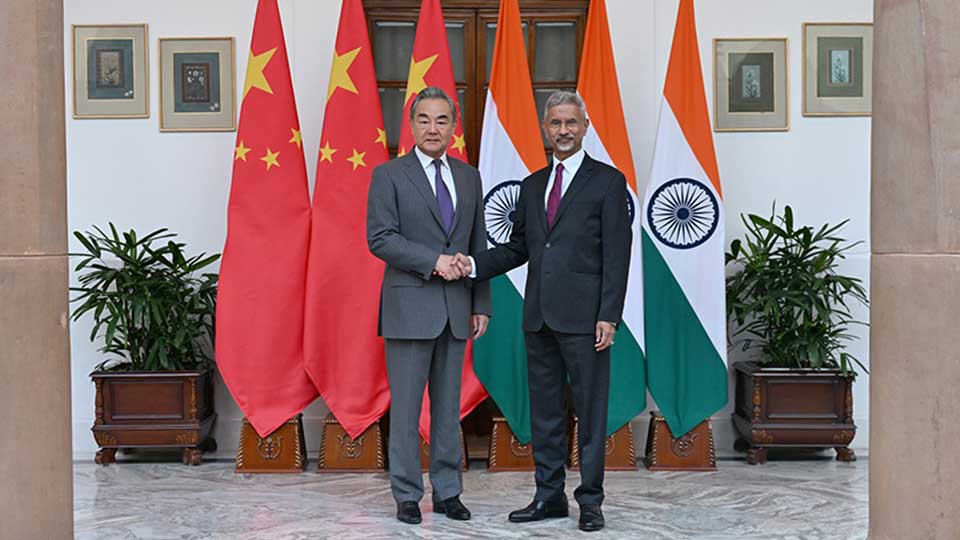

The resumption of trade at three border outposts, the establishment of bilateral working groups to help mitigate tensions over disputed territory, and mutual support for one another in hosting upcoming BRICS summits were just some of the achievements reached during Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s high-level trip to New Delhi this week.

These positive steps, alongside Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s upcoming trip to Tianjin, China, for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), are being heralded by some observers as indicative of a realignment in the region’s strategic partnerships. The improvement in ties between New Delhi and Beijing comes as the U.S.–India relationship unravels.

With U.S. tariffs on India’s purchasing of Russian oil set to kick in on August 27th, a flurry of commentaries has credited the U.S. with driving the Sino–India rapprochement. To add insult to injury, Trump spared penalizing China for its importation of Russian oil and only levied a 19% tariff on Pakistan.

Yet, as compelling as these narratives may be, it’s important to place the thaw in China–India relations in context – and to avoid conflating stability and normalization with trust or a genuine strategic embrace.

The Steady Rapprochement

The gradual improvement in diplomatic relations between Beijing and New Delhi began in October 2024, when the two countries reached an agreement on patrolling arrangements along their disputed border known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

This agreement helped facilitate a series of engagements: a meeting between Prime Minister Modi – China’s President Xi Jinping at the BRICS Kazan Summit several days later; a defense ministers’ meeting on the sidelines of the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting in November; and in December, the resumption of the India–China Special Representatives meeting, which had not been held in five years.

Momentum carried into 2025, with Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri and Minister of External Affairs S. Jaishankar both traveling to Beijing. Minister Wang Yi’s India trip—the first in three years—produced additional outcomes: resuming visas, beginning negotiations to restore direct flights, creating new mechanisms for people-to-people exchanges, agreeing to hold the Special Representatives meeting next year, and easing restrictions on trade and investment. While these are positive steps toward stability, they are not necessarily harbingers of the end of competition and contestation.

Economic Opportunities—and Persistent Frictions

There is a clear logic for improving trade and economic linkages, as China–India trade has grown year-on-year despite the political tensions. Nevertheless, actions taken by both capitals hampered similar growth in forging deeper commercial ties.

A major thorn in the relationship has been the export restrictions China maintains on a range of critical goods that undermine Indian industry. These included export controls on rare earths and critical minerals —vital for India’s electric vehicle and smartphone manufacturing sectors— and informal restrictions on critical goods leaving port. These issues were, at least for the moment, addressed during Minister Wang Yi’s trip.

The delays facing three tunnel-boring machines that were supposed to depart a Chinese port in October 2024? Resolved. Curbs on exporting fertilizer? Lifted. Restrictions on shipping rare earths minerals and magnets? Eased.

While the recent thaw may bring a measure of stability, the Sino–India relationship remains fraught with challenges, mistrust, and structural fissures that could easily derail rapprochement and put the relationship back on the ice.

This episode underscored for Indian industry and government alike the need for greater self-reliance and the urgency of diversifying away from dependence on China. Going forward, expect India to double down on enhancing local production capabilities, developing domestic value chains, and expanding rare earth imports from other actors.

Another avenue of strain is India’s ongoing attempts to shield its domestic industry from the influx of cheap Chinese goods. On August 18th, India’s Directorate General of Trade Remedies (DGTR) recommended implementing a three-year 12% tariff on steel products to curtail shipments from China. This isn’t the first instance of India imposing anti-dumping duties to protect local industries against Chinese imports; in June, the GDTR imposed duties on a wide range of Chinese products, including plastic processing machines and pharmaceutical inputs to décor paper.

Reducing trade barriers will provide vital relief to Indian industry and could reset the table for new bilateral trade and investment opportunities. Still, expectations for significantly improved economic ties should remain tempered.

Border Tensions Remain

The 2024 patrolling agreement for the disputed border may have laid the groundwork for the détente, but the situation remains far from settled. Indeed, the announcement of new working groups and mechanisms during the recent meetings in New Delhi is a positive step toward lowering tensions.

However, actions by both Beijing and New Delhi highlight how fragile the thaw remains and the depth of mutual suspicion.

In May, Beijing—seeking to assert sovereignty over Zangan (Arunachal Pradesh, as it is referred to in India)—released a new list of “standardized” names for more than 20 locations in the disputed territory. India sharply rejected the claims, reaffirming that Arunachal Pradesh will always remain an “integral and inalienable part of India.”

Roughly three months later, reports emerged that India was upgrading key border infrastructure, including the Darbuk–Shyok–Daulat Beg Oldie Road, to enhance defense mobilization. Despite some cooling, the border will remain a hotly contested fissure in the relationship.

Water Security and Strategic Distrust

The LAC isn’t the sole issue driving mistrust on the border – China’s construction of a $137 billion mega-dam on Tibet’s Yarlung Tsangpo River is stoking concern on the Indian side. With the river flowing from Tibet into the Siang River in Arunachal Pradesh before eventually forming into the Brahmaputra River, any upstream activity can have significant downstream implications.

The lack of a water treaty and China’s past behavior raise fears that Beijing could weaponize the river flow during times of conflict —an anxiety not entirely unfounded. Following the 2017 Doklam border standoff, Beijing stopped sharing hydrological data on the Brahmaputra with India, and did so again in 2022, and hasn’t shared information since. Despite External Affairs Minister Jaishankar raising the dam’s construction and need for transparency with his counterpart in New Delhi, Beijing only agreed in principle to share data during an emergency on humanitarian grounds.

It’s not lost on the Indian government or watchers of the bilateral relationship that the next destination on Minister Wang Yi’s travels was Islamabad, Pakistan.

China’s “iron brotherhood” with Pakistan and the provision of support and intelligence to Pakistan during May’s Operation Sindoor have further deepened mistrust within India. Beijing’s funding of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and push to expand the initiative to Afghanistan continues to elicit strong objections from India.

As long as China continues to provide arms to Pakistan and engage in infrastructure projects that India sees as impinging on its sovereignty, significant improvements in the bilateral relationship are going to be hard to come by.

Concomitant with the strengthening of Sino–Pakistani defense ties, India has bolstered its own partnerships—most notably with the Philippines. The early August elevation of India–Philippines relations to a strategic partnership, coupled with a recent joint patrol in contested waters, signals yet another vector of strain in India–China relations. India has also expanded its defense and diplomatic relations with Quad members Japan and Australia as a bulwark against Chinese assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific.

Unquestionably, Trump’s actions have created a chasm between Washington and New Delhi, undermining decades of painstaking diplomacy. Yet attributing the China–India thaw solely to U.S. policy is misleading. With India questioning U.S. reliability, it should come as no surprise that India is doubling down on its multialignment strategy, seeking to develop and elevate ties with strategic partners.

While the recent thaw may bring a measure of stability, the Sino–India relationship remains fraught with challenges, mistrust, and structural fissures that could easily derail rapprochement and put the relationship back on the ice.

Blake Berge is an independent Asia-Pacific geopolitical analyst based in Singapore.