By Tim Hirschel-Burns

With the notable exception of the United States, all other 192 members of the United Nations agreed on an agenda for financing the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs). In important respects, the agreement on the outcome document of the recent Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD4) is a victory for multilateralism. At the conference last week—the first such conference since 2015—it was a point of celebration that nearly all UN members had managed to come to an agreement on an important and sometimes contentious topic: the sprint to meet the Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs) 2030 deadline.

Still, the need for a breakneck sprint rather than a steady trot is indicative of how the financing of development has faced major hindrances since well before Donald Trump took office. In the 10-year period since the last FFD conference, developing countries have experienced the COVID-19 pandemic, interest rate hikes, and declines in bilateral finance from China and many Western governments. Less than one-fifth of the SDGs are on track, and the UN estimates an additional $4 trillion per year would be needed to finance them.

The freshly agreed FFD4 outcome document presents the international community’s shared stance on financing development, but it does not implement it. With the U.S. rejecting this agenda and Europe shifting its spending priorities to defense, many eyes will turn to China.

A variety of competing narratives frame China as an extremely proactive international force—China the “debt trap diplomat”, China the aspiring hegemon filling the void left by the U.S., China the “savior” to the Global South. Despite their differences, they share inflated assumptions about the scale of China’s international engagement and its desire to revolutionize the world order. In reality, China’s current approach is far too nuanced and restrained to satisfy any of these easy narratives.

Evolutions in Chinese Overseas Finance

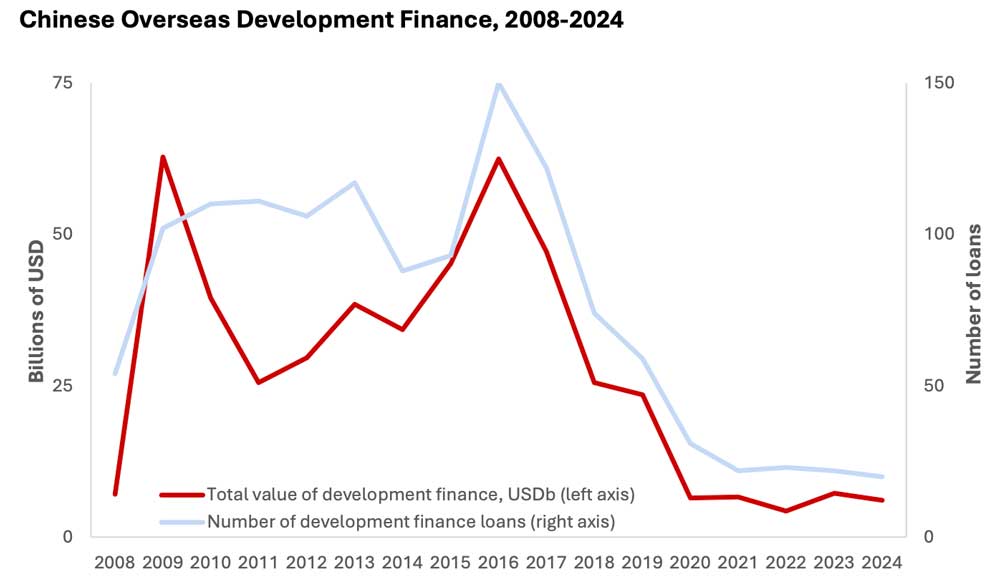

The last FFD conference took place near the height of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), when Chinese lending rivalled the World Bank’s for scale. But soon after that 2015 conference, Chinese development finance decreased dramatically. There has been a rebound in recent years, with this finance directed towards greener and less financially risky projects than earlier Chinese finance. Its scale remains far short of the BRI’s peak, though current levels still rival several regional development banks.

At a time when development finance is in desperately short supply, China has the capacity to play a more proactive role.

Western development advocates often utilize a dated narrative of Chinese development finance. They warn that when the U.S.—and to a lesser extent Europe—roll back development assistance, China is waiting to swoop in and gain a geopolitical advantage. The U.S.’ status as the sole country to withdraw from the FFD process, coupled with its chaotic destruction of USAID, does real damage to the U.S.’ global reputation. There are also ways that China has stepped in to fill the void left by the U.S. Still, China is far from showing it will provide an equivalent scale and form of overseas finance to replace retrenchments in other sources of development finance, and the status quo would mean that many development priorities just go unfunded.

China’s approach to FFD4

In important ways, China’s approach to FFD4 differed from Global North countries (leaving aside the isolated U.S.). For one, China negotiated through the G77 plus China, the confusingly named block of 134 developing countries. Further, Global North countries actively resisted calls to reform global economic governance institutions or build alternatives to them, preferring for discussions to take place in institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or World Bank, where they hold much greater voting power than in the more democratic UN. China has generally aligned more with developing countries, actively calling for governance reforms at the IMF and World Bank and supporting the UN Tax Convention process.

On debt, however, China’s position was more similar to Northern countries. China is a major creditor while the rest of the G77 is dominated by borrowers, and the G77 plus China lacked a common negotiating position on debt in the FFD process. The Africa Group, backed by a number of other developing countries, led the charge to push FFD4 to initiate an intergovernmental process on debt within the UN, which could ultimately lead to a UN mechanism to address cases of unsustainable debt.

This provision made it into the final outcome document. In statements after the document’s adoption, Global North countries announced their dissociation with that paragraph. While China did not formally disassociate itself, its statement called for improvements in the sovereign debt architecture to play out through the G20 rather than the UN.

At the FFD conference itself, China was relatively quiet, participating in fewer events and announcements than European countries or proactive developing countries like Brazil, Kenya, or South Africa.

The Path to Financing Development

At a time when development finance is in desperately short supply, China has the capacity to play a more proactive role. Its massive advancements in the production of clean energy technology make it a vital partner in the global fight against climate change. Developing countries could also form increasingly important trade partners as tariffs disrupt U.S.-China trade.

And while FFD4’s calls for scaling up multilateral development banks (MDBs) could hit walls at the many such banks where the U.S. holds veto power or close to it, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank—in which China plays a leading role—are among the most prominent MDBs that lack the U.S. as a member.

At the recent BRICS Summit, China and other BRICS members laid out a vision of an international financial architecture that remains multilateral but better serves the interests of developing countries. China’s globally active national development banks—the China Development Bank and the China Export-Import Bank—provide another option. China’s policy rate is now comparable to rates from the International Development Association (the World Bank’s concessional arm), meaning that long-run financing and refinancing through its policy banks in RMB could create new fiscal space for development.

The agreement underlying FFD4 is not perfect, but it contains many proposals that could help reverse the shortfalls in financing for development. Someone will have to turn the words into action. As the 2030 SDG deadline approaches, it would be easy to make China a convenient prop: either to deflect responsibility for saving the SDGs onto China or to blame China for the SDGs’ demise. In reality, stepping up financing for development is an urgent and attainable task, and China can be an important actor in these efforts. But these efforts will demand global action that goes well beyond any one country.

Tim Hirschel-Burns is a Policy Liaison at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center. He is a legal expert working on financial stability for development, climate and development finance, and trade and investment rules.