The 4th Ministerial Meeting of the China-CELAC (which stands for Community of Latin American and Caribbean States) Forum closed with the unveiling of the 4th Joint Plan of Action for Cooperation in Key Areas (2025-2027). Since its formal establishment ten years ago, the Joint Plans of Action for Cooperation have remained key documents in understanding the dynamics of the forum as an informal yet complex multilateral mechanism. The 4th Joint Plan of Action marks a significant departure from its preceding documents (2015-2019, 2019-2021, and 2022-2024).

Instead of focusing on multiple areas of cooperation, as previous documents did, the 4th Joint Plan of Action aims to consolidate China-Latin America and the Caribbean relations as a partnership of civilizations. It also expresses a willingness to deepen the so-called win-win partnerships in the region while also establishing a common front to tackle global challenges.

Why It’s Important

The entire world is currently affected by the strategic competition between China and the United States. Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is no exception. New developments in the region highlight its strategic importance for both Washington and Beijing. Understanding this new joint plan of action is crucial for navigating the present and future dynamics in an ecosystem characterized by strategic competition.

Framing the 4th Joint Plan of Action as a mere continuation of China’s LAC policy ignores the changing nature of the political environment in LAC and domestic developments in China. In the wake of the COVID pandemic and heightened geopolitics, Beijing has reconsidered some of its strategic objectives in LAC. This document shows China’s hand in its strategic competition with the United States in LAC relations.

While the U.S. is yet to develop a strategy and partnerships for that competition, China has one, and the 4th Joint Plan of Action provides us insight into this strategy. The document also contrasts with the “cooperate or else” approach currently in place in Washington, by forging partnerships with like-minded states such as Brazil, Chile and Colombia.

By not excluding any state and building ties through cooperation with a group, Beijing is arguably trying to bring undecided states into China’s camp. It remains to be seen what Washington’s response will be and if this group of undecided LAC countries will pick a side or find a way to work with both superpowers.

The 4th Plan of Action for Cooperation departs from its predecessors in one relevant aspect: it is not solely focused on simple cooperation. Rather, it serves as the blueprint for a strategic association – some would even call it an alliance – not between LAC and China, but between civilizations.

A China-LAC Alliance?

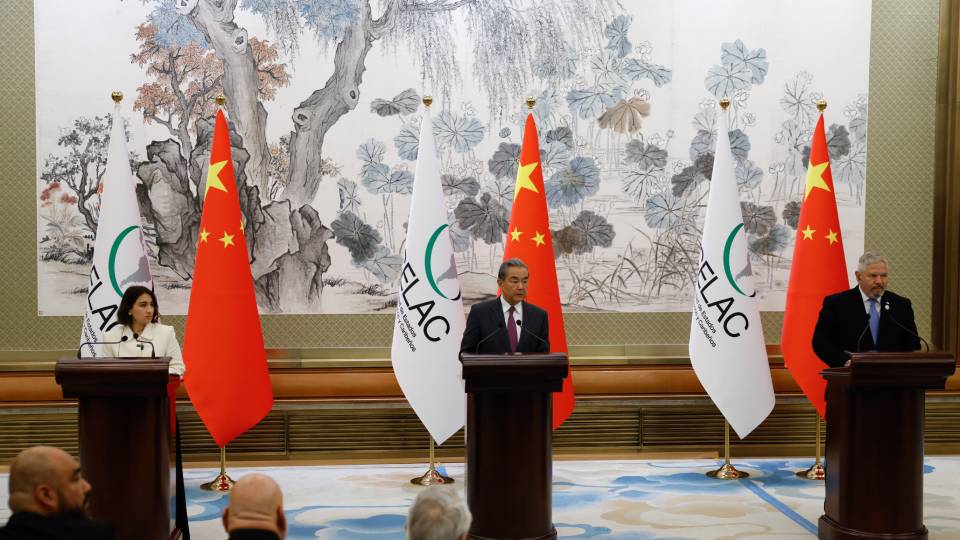

The presence of presidents such as Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula Da Silva, Chile’s Gabriel Boric, and Colombia’s Gustavo Petro at the 2025 Ministerial Meeting of the China-CELAC Forum was highly meaningful. Together with Mexico and Argentina, these countries comprise the bulk of regional power. The new Joint Plan of Action builds on this critical mass and emphasizes the need to continue with this type of high-level exchange. Most importantly, it does not circumscribe their agenda to China-LAC “bilateral issues”, but addresses “major international and regional issues” in order to safeguard “interests of the Global South”.

This implies an ambition to form a broader alliance between China and LAC. In an era where the U.S. appears to disregard alliances, a model of collaboration between China and the LAC would send a powerful message to the Global South and grant Beijing a significant foothold in its competition with Washington.

Historically, LAC has lacked the necessary cohesion to form a regional alliance. It tends to work with as many organizations and alliances as there are states in the region. In the absence of a cohesive internal alliance, the idea of a China-LAC alliance to tackle major international and regional issues sounds like wishful thinking. Two recent developments perfectly exemplify this.

The first is centered on existing dynamics within CELAC. As an informal mechanism, CELAC operates based on consensus. This, for example, allowed Argentina and Paraguay to block the adoption of the closing declaration of its 9th Summit of Heads of State and Government. The China-CELAC Forum is an informal multilateral cooperation mechanism not bound by this consensus rule. However, any major joint measure would arguably still have to gain CELAC approval, which raises the issue of consensus again.

In the second place, Argentina did not take part in the 4th Ministerial Meeting of the China-CELAC Forum. This was another attempt from Buenos Aires to distance itself from Beijing. This, as well as the fact that CELAC members Paraguay, Guatemala, Belize, Haiti, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines all maintain ties with Taiwan, makes getting the necessary consensus for an alliance a long shot.

Aside from the high-level exchanges, the 4th Joint Plan of Action aims to expand people-to-people exchanges at other levels, including those between legislative bodies. This deserves further analysis as it could mean that China will aim at increasing its presence in regional parliaments. It is essential to note that China is an observer state to the Latin American and Caribbean Parliament (PARLATINO) and, in 2023, was granted observer status at the Central American Parliament (PARLACEN).

China could also try to obtain a similar status at the Andean Parliament and MERCOSUR’s South American Parliament (PARLASUR). An already broad network of twin towns and sister city agreements between Chinese and LAC municipalities adds to these ties. 180 such partnerships have been concluded with 17 countries.

4th Joint Plan of Action for Cooperation (2025-2027) pledges:

- China will invite 300 political party officials from CELAC States for a visit.

- The China-LAC Political Parties Forum will continue.

- The Chinese government stressed its willingness to provide LAC countries with credit funds of RMB 66 billion ($9.1 billion).

- Beijing will provide 3,500 government scholarships and 10,000 training opportunities in China to CELAC members from 2025 to 2027.

- The role of Confucius Institutes and Confucius Classrooms will be enhanced in teaching Chinese, including through workshops, programs, scholarships, and books.

- Journalists and media professionals will be invited for short and medium-term visits to China, including 500 opportunities for capacity-building workshops and training.

The Beijing Consensus: Deepening Mutual Benefit and Win-Win Partnerships

The document also promotes the establishment of cooperation in the realms of (1) economy, trade and investment, (2) finance, (3) infrastructure, (4) agriculture and food security, (5) industrial and information technology, (6) energy and resources, and (7) customs, taxation, standardization and personnel movement. China’s Global Development Initiative provides a general framework and the Joint Plan of Action by design prioritizes China geostrategic objectives in LAC.

It also aims at contrasting the Beijing Consensus with Washington’s. For example, it advocates for strengthening coordination under the WTO framework – echoing the Washington consensus – while also promoting the establishment of an alternative cooperation mechanism to resolve trade differences – a Beijing consensus goal.

It also seeks to promote close dialogue and cooperation between the development banks of China and LAC. This excludes the Inter-American Development Bank, where the U.S. is a major shareholder and partner, while promoting the Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean, which, by definition, excludes the U.S., as a viable partner and an entry point for Chinese development banks to the region.

Cooperation on infrastructure also seeks to reinvigorate the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). With the addition of Colombia to the BRI, Beijing rebalanced Panama’s withdrawal. Nonetheless, the Plan of Action actively enhances China-CELAC partnerships in roads, railways, bridges, ports, and tunnels, irrespective of their formal or informal links with the BRI.

It also aims at developing a concept of “friendly ports” based on sister city models. Early examples include Chancay Port in Peru and the ports of Balboa and Cristobal in Panama. Despite the document’s wide range, it fails to tackle key questions such as the strategic dependency of certain LAC food industry sectors on the Chinese market or the influx of EVs and solar panels due to high levels of production in China.

China’s President Xi Jinping (L) and Chile’s President Gabriel Boric attend the opening ceremony of the Fourth Ministerial Meeting of the Forum of China and Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) in Beijing on May 13, 2025. (Photo by Pedro PARDO / AFP)

A Partnership Among Civilizations

Another notable issue is the document’s inclusion of soft power tools under the name of inter-civilizational exchanges, a departure from previous plans. This is part of a broader trend that China has used for exchanges with countries like Egypt and Ethiopia, as well as the wider African region.

In the case of LAC, these inter-civilizational exchanges include culture and art, as well as cooperation between educational institutions and think tanks, particularly through academic seminars, talent training, scientific research, and scholarships. Local government exchange and media and communications cooperation also feature in this new framework.

A Common Front in the Face of Global Challenges

One of the most important departures of the new joint plan of action for cooperation with its predecessors is its focus on global challenges. While previous documents mentioned broad fields like climate change, health and trade, the new document also specifies global security, including cybersecurity, terrorism and its financing. This establishes an indirect link with Beijing’s Global Security Initiative.

The document also includes an anti-corruption component, highlighting the importance of using existing United Nations frameworks with the goal of signing bilateral law enforcement and judicial cooperation agreements on mutual legal assistance in criminal matters. Relatedly, cooperation on police and law enforcement is prominent. The document pledges to explore models between China and LAC for combating the production, consumption, and trafficking of drugs, perhaps referencing fentanyl.

Other pressing global issues raised in the document include poverty eradication and development, climate change and environmental protection, integrated disaster risk management and resilience building, scientific and technological innovation, digital technology, and health cooperation.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing the Plan of Action

The new plan of action recognizes that its areas of implementation are neither exclusive nor comprehensive; they require a certain degree of flexibility and voluntary buy-in. It also clarifies that this new framework will not affect other bilateral or multilateral cooperation projects previously agreed to.

In summary, the 4th Plan of Action for Cooperation departs from its predecessors in one relevant aspect: it is not solely focused on simple cooperation. Rather, it serves as the blueprint for a strategic association – some would even call it an alliance – not between LAC and China, but between civilizations. In so doing, it offers a global outlook aiming for mutual benefits and win-win partnerships for the Global South amid geostrategic competition between two superpowers.

Alonso Illueca is CGSP’s Non-Resident Fellow for Latin America and the Caribbean.