By Bunthorn Khath and Chanrith Ngin

When Cambodia co-sponsored the United Nations resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, it was viewed as a significant shift in its foreign policy, paving the way for its rapprochement with the West and signifying a partial shift and independent or diversifying from the previous pro-China stance. After all, Cambodia and Russia are China’s allies and Russia is Cambodia’s “old friend”. But such perceptions are overblown: even with the tilt towards the West, Sino-Cambodian relations remain as strong as ever.

On the face of it, it does appear that Cambodia has leaned towards the West following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. From 2022 to late 2023, while Beijing became more pro-Russia, Cambodia consistently backed the West in the Ukraine-Russia war.

The relationships between Cambodia and the West have improved. The Cambodia Democracy Act of 2021 was stalled in the U.S. Senate, although it had been passed by the House of Representatives. The Act aimed to impose sanctions on high-ranking Cambodian government officials who were allegedly involved in democratic setbacks. The decision was validated when President Joe Biden attended the ASEAN summit in Cambodia in November 2022 and personally thanked Cambodia for its position on Ukraine. Washington reversed its critical position on the outcome of Cambodia’s “neither free nor fair” July 2023 election and restored its US$18 million foreign aid to Cambodia two months after freezing it. The US and EU have also become less critical of Cambodia’s human rights record.

Cambodia’s foreign policy diversification has been reaffirmed by its new leader, Prime Minister Hun Manet. With foreign policy diversification, Cambodia can improve its relations with both the West and China at the same time. Tilting towards the West is not necessarily to the detriment of its relations with China.

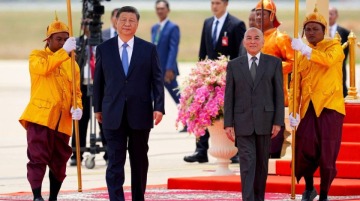

Sino-Cambodian relations remain close. Chinese President Xi Jinping called then-Prime Minister Hun Sen two days before the UN vote. Both leaders “agreed to hold a balanced and fair position on the Ukraine situation.” Hun Sen hinted a few days later that an unnamed country had lobbied Cambodia to abstain from voting along with Laos and Vietnam (the unnamed country was understood to be China). Hun Sen said he had ignored the suggestion. The behind-the-scenes lobbying by China underscores the close ties between the two countries.

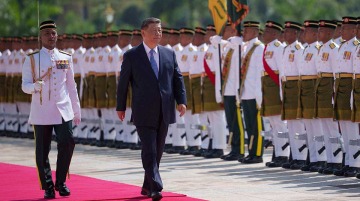

In May 2024, Cambodia named a Chinese-built road in Phnom Penh after Chinese President Xi Jinping. It is the first major street in the capital named after a foreign figure since the 1960s. Naming a street after foreign leaders symbolises Cambodia’s strong diplomatic ties with other countries.

In June 2024, Phnom Penh endorsed the China-Brazil peace proposal to resolve the Russia-Ukraine crisis while refusing to attend the Ukraine Peace Summit held in Switzerland. China was deemed to have influenced Cambodia’s decision since Russia was not invited to the summit. (Phnom Penh denied that Beijing had sought to influence it). Meanwhile, Ukrainian diplomats have visited Phnom Penh to ask Cambodia to support its peace initiative, but no positive response from Cambodia has been reported.

With foreign policy diversification, Cambodia can improve its relations with both the West and China at the same time. Tilting towards the West is not necessarily to the detriment of its relations with China.

China remains Cambodia’s top investor and donor, providing support to the latter’s critical infrastructure. The Funan Techo Canal project is an indicator of Beijing’s firm support. The US$1.7 billion waterway, which is mainly funded by China, is expected to reduce Cambodia’s dependence on Vietnam for its Mekong trade. Amid the tensions between Cambodia and Vietnam over the project, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi arrived in Phnom Penh to show solidarity with its closest Southeast Asian ally. Weeks after Wang’s visit, the two countries’ militaries conducted a massive annual military drill at Ream naval base that lasted for fifteen days.

On top of that, Beijing sent its influential diplomat Wang Wenbin as a new ambassador to Cambodia in July 2024. Wang was a former spokesman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a “wolf warrior” diplomat with a combative approach to international relations.

One month before Wang’s arrival, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin paid a one-day visit to Cambodia. It was seen as the American attempt to improve its relations with Cambodia to counter China’s increasing influence. However, the outcome was modest, with only a commitment to restoring humanitarian and security cooperation.

In short, Cambodia has adopted a flexible approach in its foreign policy posture with the great powers, depending on domestic politics and external pressure. Standing with the West on the Ukraine war seemed to indicate its divergence from Beijing. But the move was meant to reduce Western pressure on domestic issues. Thus, the claim that Cambodia has balanced its foreign policy to divert from Beijing’s orbit is overblown: in fact, Sino-Cambodian relations have become more entrenched. For now, taking a real middle path remains strategically expedient for small states like Cambodia to navigate great power competition.

Khath Bunthorn is a Research Associate at the Center for Governance and Inclusive Society, Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI), Phnom Penh.

Dr Chanrith Ngin is an Honorary Academic at The University of Auckland, New Zealand. He is also a Senior Research Fellow (non-resident) at the Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI). He was a Wang Gungwu Visiting Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

This article was originally published on Fulcrum and republished with the permission of ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute