For decades, global climate action has been largely shaped by the Global North—through frameworks like the Paris Agreement and funding mechanisms such as the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JET-P). These initiatives have set the tone, the goals, and the financial flows, often leaving countries in the Global South as recipients rather than architects of their energy future.

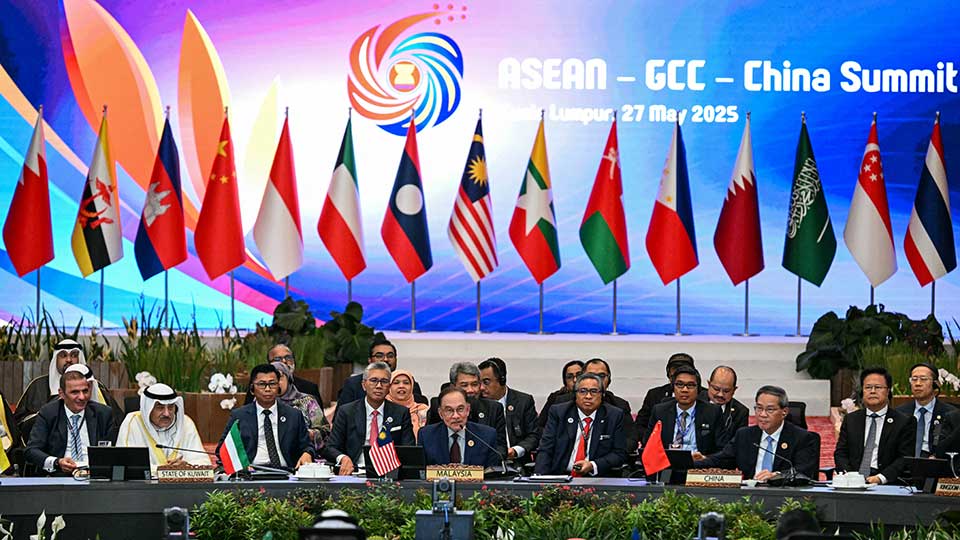

The 2025 ASEAN-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)-China Summit in Kuala Lumpur can be seen as a potential turning point—a sign that the Global South might take a more active role in shaping its own clean energy transition. The idea of a trilateral axis linking Southeast Asia, the Gulf, and China could inspire hope for a fresh, South-led approach that complements and eventually shifts the existing climate architecture.

While the summit’s final communiqué was notably vague, heavy on broad commitments and light on new funding or formal agreements, it nevertheless signals an important opening. The document reaffirmed support for the Paris Agreement, highlighting that even this emerging South-South dialogue remains rooted in global norms that have long guided climate action. But reaffirmation does not preclude innovation—it simply grounds this new cooperation in a shared global ambition.

The real promise of this ASEAN-Gulf-China axis lies in the regions’ shared urgency to meet rapidly growing energy needs with cleaner alternatives—and their desire to bypass the delays and misalignments that often come with donor-driven approaches.

For countries like Indonesia, which have faced slow disbursement of climate finance under existing mechanisms, this more direct and pragmatic cooperation offers an appealing alternative.

Ambitious ideas were raised at the summit, including infrastructure projects such as cross-border transmission lines and subsea cables to connect renewable energy assets across these regions. While these remain aspirational, the fact that such concepts are being discussed signals a shift in thinking toward more integrated, regional solutions.

Technology transfer is another key area of potential. China leads the world in solar panel manufacturing and battery technology and could play a pivotal role in elevating regional capacities. True success, however, hinges on ensuring that knowledge transfer is equitable and fosters local innovation and capacity-building. Past experiences have revealed challenges, but the summit’s emphasis on partnership provides an opportunity to reset and improve these dynamics.

Environmental and social responsibility must remain front and center. Some investments, like Chinese-backed nickel mining in Indonesia, have raised concerns over labor and ecological impacts. The clean energy transition must be not only low-carbon but just and sustainable, avoiding the pitfalls of previous energy developments.

A bright spot from the summit was the focus on workforce development. Clean energy transitions are as much about people as technology. Prioritizing education, upskilling, and inclusive workforce policies can ensure that green growth creates durable economic opportunities and benefits local communities.

The most significant challenge ahead is financing. The summit did not bring new capital commitments or funds to the table. Mobilizing the massive investment required to transform energy systems will demand creative financing models—blended finance, green bonds, carbon markets—and strong public-private partnerships, especially for capital-intensive infrastructure like grid modernization and offshore wind.

Equally critical is building formal governance structures. Without clear rules, binding agreements, and transparent processes, cooperation risks fragmentation and inefficiency. The summit marked a first step, but robust frameworks are needed to turn potential into action.

Despite these challenges, the ASEAN-Gulf-China summit holds real promise. It is a hopeful sign that regions with diverse interests and histories are exploring new ways to work together on one of the defining issues of our time.

If ASEAN, the Gulf, and China can build on this momentum—with transparency, equity, and ambition—they could pioneer a more Global South–attuned, pragmatic approach to the energy transition. This would not only accelerate progress in their own regions but also offer a valuable model for other parts of the Global South seeking alternatives to traditional climate finance and cooperation.

In an era defined by climate urgency, new partnerships and innovative approaches are critical. The summit underscores the Global South’s growing desire to lead and shape its own destiny. The real test will be whether these aspirations translate into concrete projects, financing, and governance.

For now, the summit is a hopeful beginning—an invitation to watch, support, and engage as this trilateral axis seeks to turn promise into meaningful progress.

This article was co-authored by Yeta Purnama, a researcher at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), and Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at CELIOS.