By Chris Alden

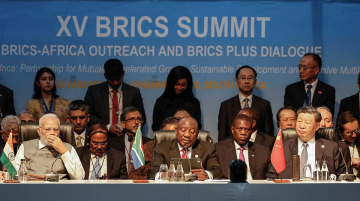

What happens when a card-carrying BRICS member has an election and changes government? Do changes in domestic politics produce changes in policy towards BRICS? South Africa’s recent election in which the leading internationalist party – the governing African National Congress – has had to enter into a coalition government for the first time since 1998 stands out as a moment that could produce a foreign policy reappraisal.

The Democratic Alliance, its coalition partner, has a record of reaching out to Taiwan authorities, generating speculation in the past that if one day it were to get into power, it would restore recognition of Taipei over that of Beijing. That’s not going to happen, but there are areas where South African foreign policy will distance itself from BRICS, or at least the explicitly Russian and implicitly Chinese position on the invasion of Ukraine.

Indeed, even before the general election South Africa had begun to shift away from the kind of policy prevarication that led many to think it was unequivocally supporting Moscow. But, while a new skepticism towards BRICS might now enter South Africa’s foreign policy vocabulary, the fact is South African international standing is enhanced by membership with the ‘alternative’ to the West’s G7 as it is with its position on the G20.

Moreover, this isn’t the first time that a BRICS country has had a change in government. Brazil’s election in 2019 brought the army captain Jair Bolsonaro into power, partly fanned by anti-Chinese populism. In his words, ‘China isn’t buying in Brazil, it is buying Brazil’. A distinct cooling of ties with BRICS ensued, though, after a year and the absence of attractive Western financial support as well as limited Western assistance in tackling COVID-19, Bolsonaro had become an advocate of China’s role and a participant in BRICS.

Of course, lest you think that electoral changes producing policy shifts is a distinctively BRICS or ‘Global South’ problem, consider the disruption caused by a right-wing party taking power in institutions like NATO or the European Union. Perhaps great powers just learn to live with the jostling and sometimes jeering crowd of allies. As Andrei Gromyko reportedly said in 1973, “In the interests of our common task, we must sometimes overlook their (our allies) stupidity.”

Professor Chris Alden is the Director of LSE IDEAS