Indonesia is advancing plans for its first nuclear power plants, with Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) from China and Russia leading the shortlist. Jakarta is drafting new uranium regulations after confirming deposits in West Kalimantan, as it targets reactor deployment by 2030–2032.

“We are currently preparing the government regulation (PP). We hope the new regulation will enable the processing and refining of radioactive materials for energy use,” Deputy Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Yuliot Tanjung said in Jakarta yesterday.

Indonesia’s entry into nuclear energy marks a strategic pivot in its long-term decarbonization and energy security agenda, but it comes with financial, regulatory, and geopolitical challenges.

Nuclear Regulation Under Review, Domestic Uranium Confirmed

Indonesia is pursuing its uranium ambitions based on confirmed deposits in Melawi Regency, West Kalimantan, where the geological resource atlas identifies 24,112 tons of uranium.

This is the first time nuclear policy has been formally linked to local uranium reserves.

“We are organizing licensing for radioactive resource areas, and because it involves mining, the oversight must be stringent,” he said.

The upcoming regulation will enable uranium processing, refining, and licensing, paving the way for domestic nuclear fuel use, a major step for energy sovereignty.

China and Russia Nuclear Technology Shortlisted

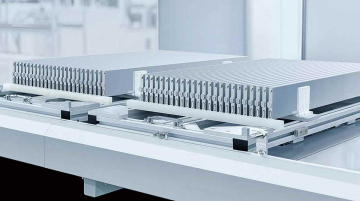

Indonesia has narrowed its vendor shortlist to China and Russia, both offering SMR models. Indonesia dropped preliminary discussions with Canada and South Korea because both focused on Large Modular Reactors (LMRs), which the Energy Ministry deemed unsuitable.

“Canada was ruled out. In South Korea, we also explored the option, but it turned out they are focused on large-scale capacities,” Yuliot said.

Russia, for its part, has directly signaled high-level political support for a nuclear partnership with Indonesia, following a bilateral meeting between President Vladimir Putin and Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto last Thursday in St. Petersburg.

“We are also open to cooperation with our Indonesian partners in harnessing peaceful nuclear energy. This could include joint projects using nuclear technologies for non-energy purposes in medicine and agriculture, as well as training personnel for Indonesia’s national nuclear industry,” said Putin.

Indonesia is considering Chinese nuclear technology based on years of prior cooperation.

Indonesia’s cooperation with China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) dates back to 2015. In October 2023, CNNC’s overseas arm, CNOS, signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with BRIN to expand collaboration on peaceful nuclear technology.

First Nuclear Reactors by 2030–2032

Indonesia’s 2025–2034 national electricity roadmap, RUPTL, sets a target of 500 MW of nuclear capacity by 2030 or 2032, with sites planned in Sumatra and Kalimantan.

“We are looking at 2030 or 2032 to begin operation. So we must prepare all the supporting regulations for PLTN,” said Energy Minister Bahlil Lahadalia.

Still, nuclear will remain a tiny share of Indonesia’s energy mix: 0.1% by 2032 and 0.6% by 2034

This cautious entry reflects the sector’s cost, complexity, and political risks.

High Costs Raise Red Flags

While momentum is growing, financing remains a critical barrier. Nuclear plants, especially small modular reactors, may not be cheap. $6,000–$7,000 per kW and for 500 MW: US$3–5 billion in upfront capital

“Electricity could cost 2.5 times more than coal,” warns Fabby Tumiwa, Executive Director of the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR).

Decommissioning and waste disposal costs, currency risks from dollar-denominated equipment and services, and unclear power pricing models pose key financial and technical risks, especially if nuclear power requires subsidies to remain competitive.

“If nuclear requires subsidies, it could undermine the clean energy case,” Fabby said.

A Question of When, Price, and Cost

The final decision between China and Russia will influence Indonesia’s technology transfers, financing models, and geopolitical alignments in energy diplomacy.

A Chinese win would extend Beijing’s influence in ASEAN’s energy transition, while a Russian win would expand Moscow’s strategic presence in Southeast Asia’s civilian nuclear market.

Indonesia’s nuclear program is moving out of the planning phase, propelled by uranium discoveries, modular reactor’s interest from China and Russia, and a political drive for cleaner, reliable power.

The Indonesian government now faces a tight window to finalize uranium regulations, to secure safe, affordable financing, and to decide on its long-term nuclear partner.