By Yan Wang and Yinyin Xu

Public assets are a vast unknown and untapped resource. Consisting of real estate and operational assets, public assets include a country’s state-owned land, transport, and utilities, as well as its liquid financial assets and state-owned corporate assets. Unlike listed equity assets, public wealth is unaudited, unsupervised, and often unregulated. Sometimes, it is even almost entirely unaccounted for.

The value of public commercial assets is estimated to be twice that of global stock markets, and twice that of global GDP. In Africa, the total value of public assets is most likely in excess of $5.2 trillion. If these assets were professionally managed, they could generate an additional $80 billion in revenue every year (or 3 percent of GDP annually), more than most countries collect in corporate taxes. Currently, government-owned operational assets are on average a third less productive than private firms.

The current narrative on debt sustainability often ignores the issue of what a government owns (assets) versus what it owes (liabilities). While conventional approaches largely focus on the liability side, a country’s public assets can be vital to its development and debt sustainability.

African countries have seen the largest, fastest, and most broad-based debt accumulation in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation, with unprecedented capital outflows leading to liquidity crises, currency depreciation, and worsening debt distress in some countries. Debt restructuring through the International Monetary Fund (IMF) would necessitate a major contraction in public debt and investment that may have an anti-investment bias and could lead to recessions. Additionally, a recent study found the IMF’s structural adjustment programs, which require countries to undertake policy reforms in exchange for loans, undermine investor confidence and increase sovereign borrowing costs.

In our new working paper, we voice concerns from the Global South that the debt sustainability analysis (DSA) framework ignores the value of public assets. For example, African debt looks rather grave when using the DSA lens, but the situation appears less so when public assets are considered. If accounted for properly, the continued accumulation of public assets would not only leave African governments with a better debt profile than conventional approaches but would also contribute to long-term economic growth. See for instance, Singapore, where a major source of its economic attainment was the creation of robust economic institutions and the effective use of public assets. This approach helped Singapore transform itself into an advanced economy in a single generation.

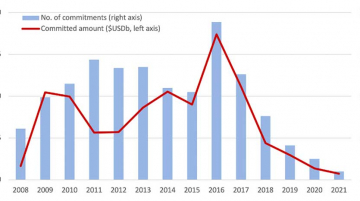

China has been a critical partner in providing development finance for the creation of public assets in Africa. Of 3,126 completed infrastructure projects co-financed and jointly built by China and African host countries between 2000-2017, 76.1 percent of hard infrastructure projects and 73.4 percent of soft infrastructure projects addressed bottlenecks in their respective sectors. Indeed, Chinese financed projects helped African countries build and upgrade nearly 100,000 km of highways, more than 10,000 km of railways, nearly 1,000 bridges and 100 ports, and 66,000 km of power transmission and distribution. They also helped install 120 gigawatts (GW) of power-generating capacity, a communications backbone network of 150,000 km, and a network service covering nearly 700 million user terminals.

These projects are now part of the host country’s public operational assets, generating essential social services, jobs, government revenues, exports, and growth. If the host government wishes, the assets could also be put up for initial public offerings or as added value to sovereign wealth or public wealth funds, or national pension funds.

It is time for markets and rating agencies to look more kindly at the increase in public debt if there are productive assets on the other side of the balance sheet. IMF data on government assets shows that when governments know what they own, they can make better use of the assets for the well-being of their citizens. Improved management of government assets may also have a positive impact on a country’s sovereign credit rating, which affects its cost of borrowing. What is more, the monetization of public assets generates receipts that can be used to pay down existing debt, reducing the need for borrowing while building a government’s financial buffers.

Ultimately, in an environment characterized by low-interest rates and high uncertainty, the best way to overcome a debt overhang is not to stop investment but to continue investing in public assets. Beyond generating a positive yield, public assets can also support green transformation, generate jobs and build revenue and economic growth.

With such an approach, African countries can build a brighter and greener future for all without going into debt distress.

Yan Wang is a Senior Academic Researcher with the Global China Initiative at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center and Yinyin Xu is an Associate Researcher and Project Manager at Furee Think Tank, a government consulting firm in Shanghai.