By Lucas Engel

Kenyan President William Ruto’s recent state visit to Washington, DC underscored considerable alignment between the U.S. and Kenya. The experience will likely boost U.S. policymakers’ confidence in the ability of the U.S. to compete with China in Kenya and other Global South countries that Beijing has lavished with development finance and diplomatic attention in the past decade.

Despite the apparent harmony of interests, considerable differences between Kenya and the U.S. remain, many of them in the area of global economic governance. Should the U.S. decide to address these concerns, widely echoed in the rest of the Global South, it may alleviate some of the grievances that currently unite Global South countries with little else in common. If China continues to vie for leadership in the Global South under these circumstances, Beijing may find itself struggling to bring together a group marked by fundamental differences and fewer shared interests.

A few days prior to Ruto’s departure for Washington, the Kenyan President called for global governance reform, an area in which U.S. intransigence has allowed China to fill the void. Ruto and other Global South leaders have long lamented Bretton Woods institutions’ inability to meet the needs of emerging markets and developing economies. In lieu of reform at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), China’s provision of development finance and currency swaps over the past decade has mitigated the negative effects of unaddressed deficiencies in the Western-led global economic order.

The U.S. has characterized China’s augmentation of that order as an attempt to establish a parallel system of global governance that aims to displace U.S. power and values and advance an order that is more accommodating to autocratic regimes. However, U.S. policymakers are reluctant to acknowledge their part in creating the pre-conditions for the rise of such a parallel order, whether real or imagined.

In fact, the Global South countries signing loan agreements and currency swaps with Chinese institutions share little in the way of common values around which China could craft a coherent vision for the future of global governance.

The BRICS grouping bundles fierce rivals like Iran and Saudi Arabia, as well as China and India. It includes countries with deeply rooted democratic traditions and repressive regimes.

Rather than a shared set of values or aims, democracies, autocracies and regional rivals in the Global South are often united through their grievances against the current system of global economic governance. Kenya is a case in point. It shares U.S. values and Ruto’s acceptance of the status of non-NATO ally shows it even welcomes the U.S.-led security architecture. Yet Ruto’s call, immediately prior to his departure for Washington, for reform of the Bretton Woods institutions is a reminder that U.S. obstinance on global economic governance reform drives a wedge between the U.S. and its partners that incentivizes them to look elsewhere.

A U.S. embrace of global economic governance reform would eliminate a focal point of agreement around which Global South countries with disparate values and visions have coalesced in the past. China’s efforts to present itself as the champion of the Global South are predicated on the assumption that the group can rally around a cause that China can claim to represent. With shared values among Global South countries in short supply, practical concerns like the deficiencies of the Western-led global economic order have held this factious grouping together. If the U.S. were to address these grievances, differences in vision and values within the Global South would likely be more difficult to bridge and China would find it more difficult to unite these countries under its leadership.

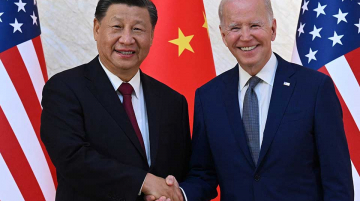

The fact that unity in the Global South, as well as the appeal of China, derives in large part from practical concerns, not shared values, also means the Biden administration’s efforts to draw democratic members of the Global South out of China’s orbit via the appeal of “democracy delivers” and other lofty ideals, is unlikely to bear fruit. This is especially true when IMF quotas and World Bank lending call the U.S.’ proclaimed adherence to its own values of equality and fairness into question.

Global economic governance reform represents an opportunity for the U.S. to live up to its values while closing the gaps that have allowed China to gain prominence in the Global South. As the U.S. seeks to delegate regional security to partners like Kenya, it should afford greater responsibility with more say in matters of global governance. The Western-led global economic order was founded on U.S. power and hegemony, but in an increasingly multi-polar world, it can only survive on consensus.

Lucas Engel is a Data Analyst with the Global China Initiative at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center.