As Azerbaijan accelerates its transition toward renewable energy, Beijing’s clean energy ambitions are finding fertile ground. The country aims to nearly double its installed power generation capacity by 2030—targeting 6.5 GW of combined solar, wind, and hydropower—with renewables expected to make up at least 30 percent of the energy mix. This target aligns with Azerbaijan’s goals to diversify its energy portfolio, expand its electric vehicle fleet, and free up natural gas for export—especially to Europe.

In this context, China’s global push in renewable energy is reshaping energy partnerships across developing regions. Nowhere is this shift more visible than in Central Asia, where countries like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have become key destinations for Chinese clean energy technology and investment. Riding this momentum, China is now extending its green influence into the South Caucasus, with Azerbaijan emerging as its next strategic frontier.

Both countries see opportunity: Azerbaijan seeks reliable, cost-effective technology to scale its renewables sector; China aims to export its renewable manufacturing power and deepen its geopolitical presence across Eurasia. Their interests converge through a pragmatic, mutually beneficial model of cooperation.

China’s Dual Role: Supplier and Builder

China’s engagement in Azerbaijan mirrors its approach in Central Asia—comprising three main pillars: supplying core renewable energy components, delivering turnkey infrastructure as an engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contractor, and forging direct partnerships with the Azerbaijani government through strategic investment agreements and competitive renewable energy auctions.

One of the factors that makes China highly competitive in this space is its dominance as a component supplier. China has a manufacturing edge due to large-scale production capacity and consistent support from government industrial policies. These advantages allow Chinese firms to offer high-quality equipment at globally competitive prices.

These price advantages are not marginal. Over the last decade, prices for solar photovoltaic modules (a type of solar panel) have dropped by over 50 percent, largely due to Chinese manufacturing overcapacity. Meanwhile, Chinese wind turbine technologies—both onshore and offshore—are estimated to be 40–70 percent cheaper than alternatives across the Asia-Pacific region. Like many others, Azerbaijan is eager to capitalize on the comparatively low costs of Chinese components to expedite its green transition.

Beyond component supply, Chinese EPC firms are increasingly active in delivering renewable infrastructure in Azerbaijan. For example, Huadong Engineering Corporation (a subsidiary of state-owned POWERCHINA) was selected as EPC contractor for the Khizi-Absheron Wind IPP, developed by ACWA Power, a major Saudi Arabian energy company with a growing global renewable portfolio.

From Contractors to Strategic Investors

Azerbaijan’s partnership with China in renewable energy is no longer limited to indirect roles through EPC contractors. It is now evolving into direct market engagement through strategic investment agreements and competitive auctions.

For Azerbaijan, China’s entry into its renewable energy market comes at a crucial time. As the country seeks to cut its dependence on fossil fuels, China offers not just capital, but also the technological capacity and industrial scale to implement large-scale renewable energy projects quickly and efficiently. In return, China gains access to a stable, energy-rich partner with increasing strategic importance in connecting green power between Europe and Asia.

An example of this partnership is Universal Energy—a Chinese renewable energy company with a growing international footprint—winning a bid in Azerbaijan’s first renewable energy auction. The company offered the lowest price per kilowatt-hour of electricity and secured a contract to develop a 100 MW solar power plant in Garadagh, an industrial district on the outskirts of Baku. This marked China’s emergence as a price leader in Azerbaijan’s renewable sector and signaled a long-term strategic foothold in the market.

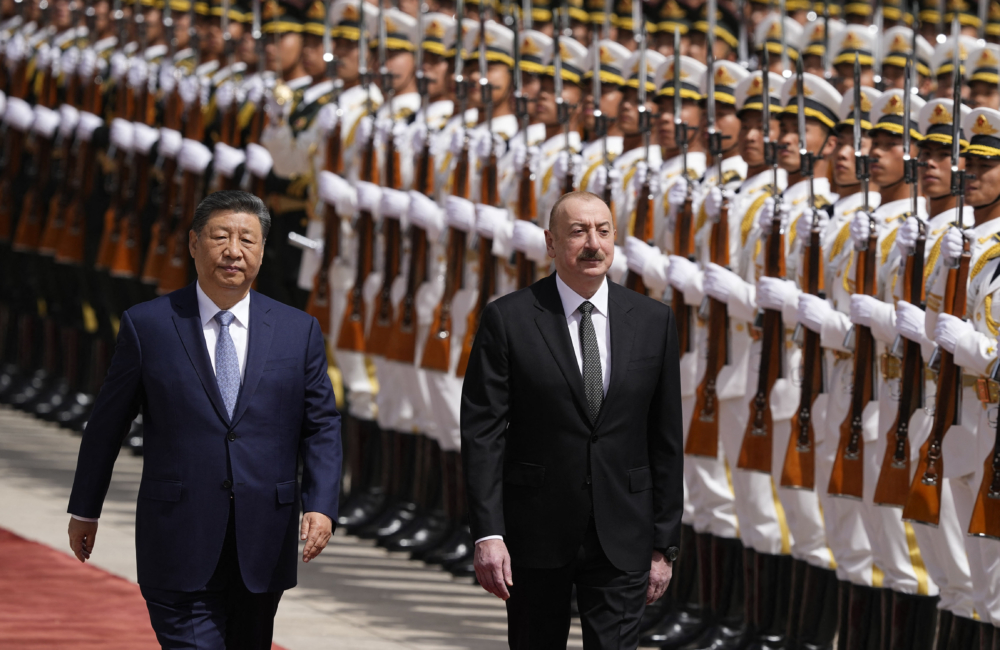

Beyond auctions, high-level diplomatic engagement is translating into large-scale energy commitments. During Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s recent visit to China, the government signed an agreement with China Energy Overseas Investment to jointly explore a 2 GW offshore wind project in the Caspian Sea.

Similarly, a deal between China Datang Overseas Investment and SOCAR Green (the renewable energy arm of Azerbaijan’s state oil company) outlines plans for a 100 MW floating solar plant on Lake Boyukshor, a polluted lake near Baku now being revitalized, integrated with a 30 MW battery storage system. This project demonstrates a shift toward more innovative, hybrid clean energy solutions in Azerbaijan’s urban-industrial zones.

These developments are not isolated—they are part of a broader strategic narrative in which Chinese engagement is helping Azerbaijan meet its energy transformation goals.

Domestic Gains: Export Revenues and Energy Efficiency

Importantly, increased domestic renewable generation frees up natural gas previously used for electricity production. For example, the Gobustan solar power project—developed in partnership with China’s Universal Energy—is expected to produce approximately 180 million kilowatt-hours of electricity annually, saving around 39 million cubic meters of natural gas.

This surplus gas can be redirected to Europe, increasing national export revenues and strengthening Azerbaijan’s position as a regional energy security partner.

The expansion of renewable power also supports Azerbaijan’s growing electric vehicle fleet, laying the groundwork for an integrated green ecosystem across energy and transportation sectors.

Toward a Replicable Model

While Azerbaijan’s current renewable energy strategy prioritizes rapid deployment, there are long-term structural considerations that warrant attention. For instance, relying heavily on imported components could limit the growth of a domestic manufacturing base.

Without strong localization strategies, the broader economic benefits—such as industrial development and sustainable job creation—may be difficult to achieve. Equally important is building human capital through knowledge transfer and technical training, to ensure Azerbaijan can operate, maintain, and expand its renewable infrastructure independently.

Other countries offer cautionary lessons. In Kenya, for example, the Garissa Solar Power Plant—built with Chinese financing and contractors—was criticized for minimal local involvement and low levels of technology transfer. It created mostly temporary construction jobs and failed to support long-term skills development or local supply chain growth.

Azerbaijan is already taking steps to avoid this outcome. A recent memorandum of understanding between the Alat Free Economic Zone Authority and Caspian New Energy, a Chinese energy investment firm, calls for the establishment of domestic production facilities for wind turbines, blades, and solar panels. This initiative aims to create jobs, foster technical expertise, and diversify the country’s industrial base.

In parallel, the Ministry of Energy and China Energy Engineering Corporation are advancing plans for a Joint Green Energy Research Center focused on workforce development and applied research in clean energy. These efforts reflect a forward-looking approach to strengthening local capacity while continuing to benefit from international collaboration.

Azerbaijan’s multifaceted engagement with China—involving infrastructure, innovation, and institutional partnerships—positions it as a green energy hub in the South Caucasus. It may also offer a blueprint for other nations seeking to engage China strategically and constructively in the global energy transition.