In Asia’s high-context politics, the stage often speaks as loudly as the words. Welcoming ceremonies, traditional dances, marathon speeches, China’s military parade, and photo ops are never just pomp. They are signals to multiple audiences. At home, they convey respect and access.

Abroad, they hint at alignment. Recent images from Beijing’s military parade and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit fell into that ambiguous space. They were prompting sharp reactions in several capitals and raising fears of diplomatic overreach.

At the Beijing military parade in early September, Southeast Asian representation included Cambodia’s King Norodom Sihamoni, Indonesia’s President Prabowo Subianto, and Laos’s President Thongloun Sisoulith. Malaysia sent its Prime Minister, Anwar Ibrahim; Myanmar’s military junta leader or acting president, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. Singapore, represented by Deputy Prime Minister Gan Kim Yong, and Vietnam’s President Lương Cường.

To better decode those signals, I spoke with Shofwan Al Banna Choiruzzad, an assistant professor of international relations at the University of Indonesia. A veteran of Track 2 exchanges and a visiting scholar at Fudan University’s Development Institute in Shanghai, Choiruzzad argues that culture is not an accessory to diplomacy: it is its very medium.

In this region, international relations are social relations. Images and gestures rarely have a single meaning. The risk is reading them as binary, turning nuanced engagement into a zero-sum game.

His prescription is deceptively simple, drawn from an older playbook: listen more, talk more. Revive Track 1.5 and Track 2 dialogues. (Track 1.5 brings officials and outside experts together in informal, often off-the-record settings; Track 2 is fully nongovernmental.)

Rebuild area studies literacy on all sides. Pair official diplomacy with patient, local listening. It may sound quaint, but Choiruzzad believes this approach often works better than the search for shiny new frameworks.

Our conversation explored how to read diplomatic theater without overreacting and what Asian governments, along with their partners in Washington and Brussels, can do to keep engagement productive, nuanced, and less vulnerable to misinterpretation.

Here’s our conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

The Conversation

EDWIN SHRI BIMO: How can we start understanding gestures and symbolism in Southeast Asia and China? Such as at the level of international politics, among others, such as in China’s military parade?

SHOFWAN AL BANNA CHOIRUZZAD: First, culture matters in international politics. International relations are social relations: relational and socially constructed, and tied to how actors perceive others and seek recognition. I am not a cultural essentialist, but long periods of social construction crystallize into specific cultures, gestures, and symbols that shape politics.

In much of this region, communication is high-context, meaning it travels not only in the words you say, but also in how you say them and the gestures you show.

During decolonization, actors practiced “world-making” and “stage-making” by crafting images, events, and symbols. At the 1955 Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, leaders joined a solidarity walk, not to change negotiation terms directly, but to signal unity and a demand for a more just, equal world.

This logic continues in the “ASEAN Way.” European or American diplomats sometimes see too many protocols or preliminaries and want to go straight to bargaining.

But in much of Asia, welcoming ceremonies, social events, how guests are received, and even seating carry meaning; seating is often alphabetical to avoid implying dominance at ASEAN or ASEAN-Plus-Three meetings.

So read both substance and setting: the stage, the gestures, the images. The entire stage sends a message. Because these cues are culturally embedded, they may not be legible to those from different traditions, which is why misreads are common.

EDWIN SHRI BIMO: How does China understand these dynamics in relation to Southeast Asia?

SHOFWAN AL BANNA CHOIRUZZAD: We can’t know precisely how messages land; this is a social process shaped by each actor’s worldview, traditions, and habits.

As a civilization (distinct from the state), China has been present in the region for thousands of years through cultural and diplomatic exchanges, and not always positively. That long history created many touchpoints, but ties in several Southeast Asian countries were also severed for long periods, so both sides still need to relearn each other. Cultural proximity is helpful, but other factors can hinder or facilitate understanding.

Messages also have multiple audiences. Take Prabowo’s visit to China: it likely signaled to Beijing, “We’re ready to be a trusted friend.” It was a rare occasion, perhaps once in ten years, and skipping it would have sent a negative signal.

In Indonesia, across Southeast Asia, and in China, social rituals, such as weddings, condolences, and neighborly calls, matter and shape how leaders communicate.

EDWIN SHRI BIMO: Speaking of that photo in China’s military parade, several Southeast Asian leaders were in it. Within the realm of politics, optics, symbolism, and gestures, each leader also conveys messages to external audiences. How should specialists in North America or Europe read those photos and the sequence of events around them?

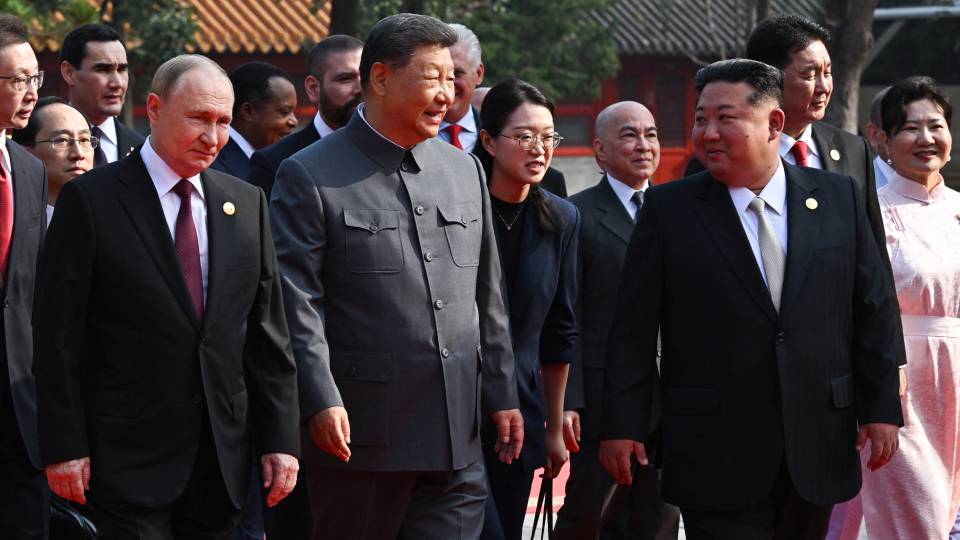

SHOFWAN AL BANNA CHOIRUZZAD: There’s a tendency to interpret the picture of Prabowo with Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-un, and Xi Jinping as meaning Indonesia has joined a Beijing-led axis. That’s an overreach. This interpretation should be reconsidered. The context is Indonesia trying to be a socially responsible partner in complex global politics. It is not a statement of allegiance.

EDWIN SHRI BIMO: U.S. diplomacy today is direct and CEO-style: decisions are made at the top. Also, public messaging is blunt, and tools like sanctions and tech/investment rules are used quickly.

I have two questions: How should Europe and the U.S. read Asia’s state-level symbols, such as China’s military parade, so they don’t misread a high-context arena? And what should Asian governments do, practically, to make this direct diplomacy work with Washington and Brussels?

SHOFWAN AL BANNA CHOIRUZZAD: Since social interaction is key, we need more engagement at both formal, official levels and at Track-Two and Track-1.5 levels, informal, non-governmental channels. Interactions have declined, and so has trust; it’s a chicken-and-egg problem. My suggestion is to intervene by creating more opportunities for interaction.

If official channels are sensitive, activate Track Two and Track 1.5 among the U.S. and China, Japan and China, the U.S. and Southeast Asia, and China and Southeast Asia.

Second, invest more in area studies. Western universities and governments have been cutting funding for area studies, yet these programs are crucial for understanding this region.

You can start with more manageable steps. U.S.–China rapprochement during the Cold War began with ping-pong diplomacy. You don’t need to start with something heavy. There was also “panda diplomacy.”

Find creative ways to generate engagement and mutual understanding. The world benefits if the U.S. and China, today’s two pivotal players, move beyond a great-power rivalry mindset toward more productive forms of interaction.

Shofwan Al Banna Choiruzzad is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at the University of Indonesia