By Zara C. Albright

Since Latin American countries began borrowing from China’s development finance institutions (DFIs) nearly two decades ago, loans from the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) have played a significant role in the region’s energy, infrastructure, and mining sectors. Borrowing from China provides clear project-level, pragmatic benefits to countries seeking financing for large, expensive projects in these areas.

In a new working paper published by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, I zoom out from these project-level factors to consider how the political landscapes in borrowing countries and globally influence Latin American countries’ decisions to borrow from China’s DFIs or the World Bank.

Through a combination of statistical analysis and a case study of Ecuador, one of the region’s largest borrowers from China’s DFIs, I find that political conditions, such as party ideology and foreign policy alignment with the United States, are key early-stage considerations for borrowing countries.

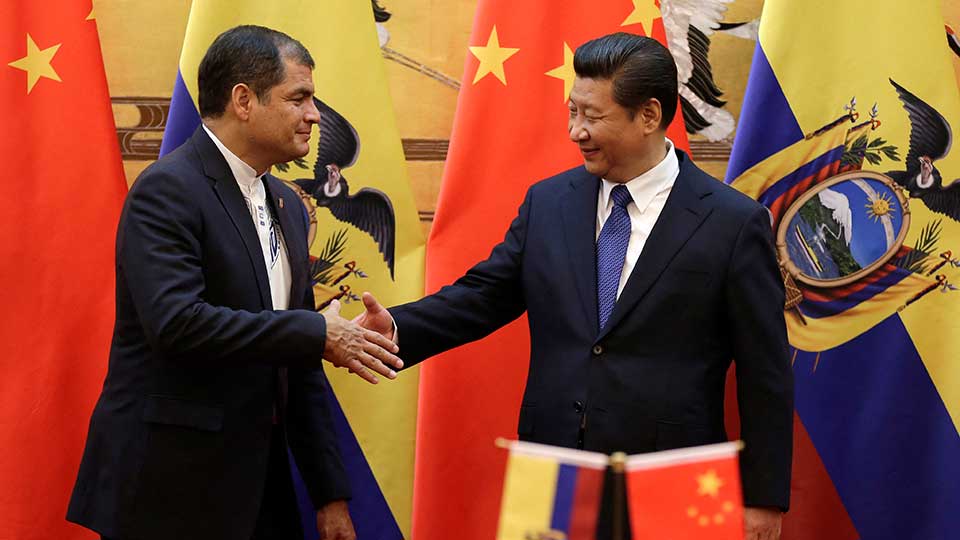

Furthermore, these political factors are related to borrowing decisions even in the presence of external constraints, such as a poor credit rating and lenders’ own preferences for certain project types and country characteristics. Countries governed by leftist parties are more likely to borrow from China for a given project; this trend was exhibited during the ten years of President Rafael Correa’s government when Ecuador borrowed over $10 billion across 21 loans.

Internationally, countries that are less aligned with the U.S. on foreign policy, as measured by voting patterns at the United Nations, are more likely to borrow from China. Additionally, as China’s relative power compared to the U.S. has grown, Latin American countries have been more likely to borrow from China for a given project.

These findings highlight a crucial, if often overlooked, dynamic of China’s relations with Latin American and other Global South countries: the agency and priorities of borrowers. Across the US policymaking community and in much of the academic literature, the emphasis is often placed on China as the actor with the agency, and the debate centers on whether it has constructive or subversive ends.

However, more recent studies, including a recent GDP Center working paper by Naa Adjekai Adjei, have demonstrated the necessity of research that supplements lenders’ goals with those of borrowing countries in Latin America and Africa.

My interviews with policymakers in Ecuador help unravel the interactions of these various factors in the process through which a loan is proposed, negotiated, and signed. At the outset, officials recognize the challenges they have in accessing credit when they face economic or political instability. After its default in 2008, Ecuador’s access to international private finance was restricted.

At the same time, President Correa’s political agenda heavily emphasized the construction of infrastructure and new hydroelectric energy facilities. Interviewees discussed the importance of the left-leaning ideology in Ecuador’s turn towards borrowing from China’s DFIs. The government’s global outlook at the time sought to diversify its international relations away from the US and towards anti-hegemonic ‘pink tide’ countries in the region, and later towards China as a perceived leader of the Global South.

This confluence of factors, including lender preferences, as well as the domestic politics and foreign policies of borrowing countries, sets the stage for Latin American countries’ borrowing decisions, prior to the negotiation of specific terms such as interest rates or maturities. Interviewees familiar with Ecuador’s negotiating process explained that these technical conversations occur after high-level political officials have identified priority projects and target lending institutions.

Identifying the various factors influencing borrowers’ choices between multiple lending options underscores the need for a broader perspective among scholars and the US policymaking community. While China’s outward push has driven much of its engagement with the Global South, countries in Latin America, Africa, and other regions have also pulled it in to serve their own needs and priorities. The discussion about China’s intentions in these regions should, therefore, include questions about whether they align with host countries’ intentions for their international engagement.

Zara C. Albright is a Global China Pre-doctoral Research Fellow with the Boston University Global Development Policy Center and a PhD Candidate in Political Science at Boston University.