On Wednesday morning in Beijing, as the People’s Liberation Army marched in lockstep through Tiananmen Square, one foreign leader stood conspicuously close to the Chinese and Russian presidents. Indonesia’s Prabowo Subianto, clad in a tailored gray suit, sat shoulder to shoulder with Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, grinning, chatting, clapping in unison as missiles and drones rolled past.

It was, on the surface, a diplomatic coup for Beijing: a Southeast Asian head of state standing in solidarity with Xi on the 80th anniversary of China’s “Victory Day.”

But for Indonesians back home, the images were jarring.

Just days earlier, their country had been convulsed by some of the most severe unrest since the 1998 riots. Several citizens had died — protesters, bystanders, even food delivery drivers — in state crackdowns.

From Jakarta to the farthest provinces, 107 sites across 32 regions still reeked of tear gas when Prabowo boarded his presidential plane for a one-night trip to China.

His government had earlier announced he would skip the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit, citing the need to monitor Indonesia’s turmoil. The foreign minister, not the president, delivered Indonesia’s statement in Tianjin.

Yet Prabowo suddenly reversed course, deciding he could make the parade after all. The reason, as his aides quietly admitted, was the “special invitation” from Xi.

This shift reveals something essential about Prabowo’s leadership. In times of crisis, when citizens demand accountability, he chooses instead the intoxicating symbolism of global stagecraft.

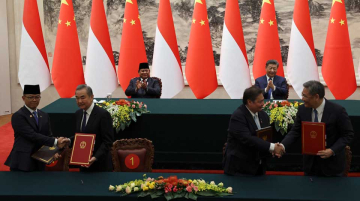

The optics were telling. Chinese protocol handlers placed Prabowo directly beside Putin and Xi — a positioning that was no accident.

Beijing’s diplomats have a keen sense of their guests’ vanity. They understand that Prabowo, who has long cultivated an image as a soldier-statesman wronged by history, relishes proximity to powerful figures.

The sight of him aligned with Putin and Xi, captured by international media, provides a tableau he craves: not as a leader embattled at home, but as a peer among global strongmen.

It is worth remembering how rare this gesture was. The last time an Indonesian president attended a Chinese national parade was in 1956, when Sukarno joined Mao Zedong for National Day celebrations. Prabowo’s presence, then, is meant to signal a historic renewal of ties.

Yet the symbolism worked less as diplomacy than as theater: China burnished its prestige; Prabowo burnished his ego.

Officially, Jakarta framed the trip as an effort to secure investments in energy, minerals, digital cooperation and military modernization. But none of these could not have been advanced through the SCO summit he chose to skip. Instead, his presence at a choreographed parade — rather than a negotiating table — suggests that substance was secondary.

Back home, the timing could not have been more grotesque. Indonesians are still mourning Affan Kurniawan, a young motorcycle taxi driver killed by a police vehicle during protests. Workers, students and ordinary citizens have filled the streets demanding an end to low wages, corruption and elite impunity.

This, then, is what Prabowo chose to leave behind for a photo-op in Beijing: the anguish of citizens who feel abandoned by their government, and a constitutional crisis of legitimacy. His message to Indonesians is clear: in a moment of reckoning, his priority is not them, but himself.

Beijing’s calculus is equally clear. For a few Chinese-Indonesian observers still haunted by the specter of the 1998 anti-Chinese riots, Prabowo’s sudden decision to show up — even for a single day — was reassurance that today’s unrest will not spiral into ethnic violence.

Indonesia gains little from this spectacle. Its foreign minister had already articulated Jakarta’s positions at the SCO summit: nonalignment, multilateralism, and solidarity with the Global South.

By contrast, the president’s appearance at a military parade projecting Chinese and Russian power muddies Indonesia’s hard-won reputation as an independent, moderating force in Asia.

The deeper concern is what this says about Prabowo’s governing instincts. Again and again, he has demonstrated that he prefers the trappings of power — uniforms, ceremonies, photo lines — to the hard labor of democratic accountability.

He may speak of stability and order, but when ordinary Indonesians demand justice for brutality, wage protection, or transparency, he is conspicuously absent. When Xi beckons, however, he flies overnight.

This is not simply bad optics; it is corrosive governance. A leader who prioritizes symbolic validation abroad while neglecting democratic demands at home is not just failing his people — he is reshaping the very meaning of sovereignty into a projection of self.

Indonesia’s place in the world will not be secured by Prabowo’s seat beside Putin and Xi. It will be secured by whether Indonesians themselves feel represented, protected and respected in their own country. Until then, the only parade worth noting is the one in Tiananmen Square — a parade not of national dignity, but of one man’s restless ego.

This article was co-authored by Yeta Purnama, a researcher at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), and Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at CELIOS.