Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto’s recent visit to Beijing yielded a joint statement that included an unexpected commitment to joint development in disputed areas of the South China Sea. This move, involving regions long contested by Indonesia and China, raised concerns about Jakarta’s evolving stance on China’s territorial claims—particularly the controversial “ten-dash line” that overlaps with Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Natuna Sea.

Indonesia has consistently rejected China’s claim to this area, especially after the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling, which declared the nine-dash line illegal under international law. The proposed joint development in disputed waters could signal a shift in Indonesia’s position, potentially suggesting a tacit acknowledgment of China’s territorial ambitions. Such a shift carries significant risks for Indonesia, including threats to its sovereignty and its regional geopolitical standing.

However, the Indonesian government quickly clarified that it does not recognize the ten-dash line. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement denying any implied acceptance of China’s claims, contradicting earlier interpretations of the announcement.

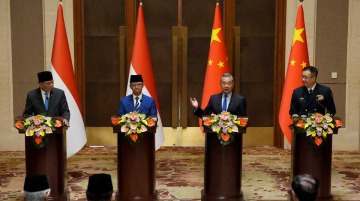

In fact, Foreign Minister Sugiono also confirmed on December 2 that Indonesia has not yet decided to create any joint maritime development areas with China in the South China Sea, directly downplaying concerns that the recent agreement undermines the country’s maritime sovereignty. He further emphasized that no areas had been identified for joint development, particularly in fishing or resource extraction, and reassured lawmakers that Indonesia’s stance on the South China Sea, including its rejection of China’s nine-dash line, remained unchanged.

This clarification aims to dispel confusion about Indonesia’s true position, though the initial ambiguity following Prabowo’s visit to Beijing continues to raise questions, particularly why did he make such a move?

As argued by Indonesian political scientists Radityo Dharmaputra and Ahmad Rizky M. Umar, under the leadership of Prabowo, there appears to be a shift away from traditional multilateralism. Adopting a more pragmatic approach, Prabowo emphasizes strengthening bilateral relations and direct engagement with global powers such as the United States and China.

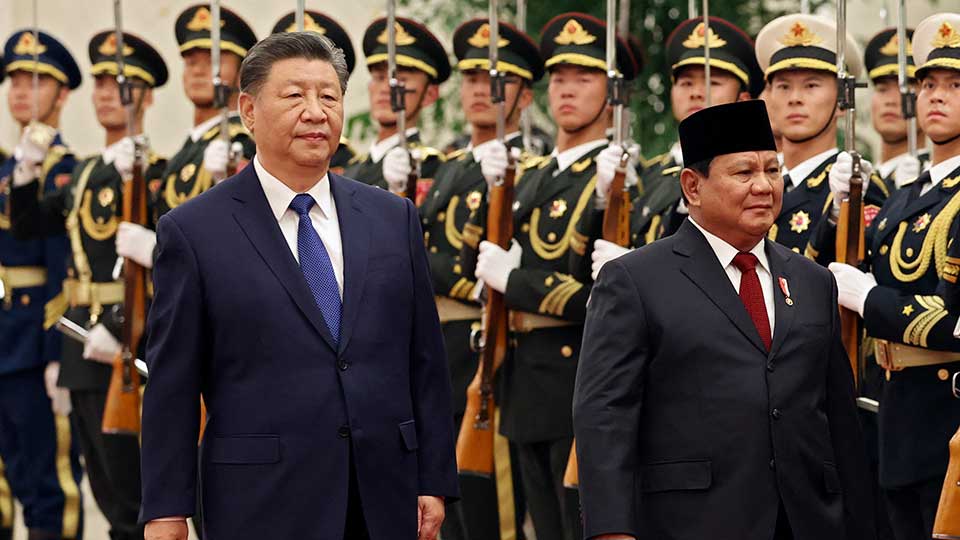

Prabowo clearly understands the strategic importance of Indonesia’s geopolitical position and aims to maximize its potential. Unlike his predecessors, who were largely ASEAN-centric, Prabowo is transforming Indonesia’s foreign policy through more dynamic bilateral engagement. For instance, his effort to deepen ties with China—Indonesia’s largest trading partner and foreign investor—is viewed as a strategic move, especially given the declining economic influence of the U.S. in the Indo-Pacific region.

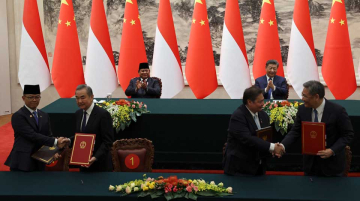

This was exemplified by Prabowo choosing China as the first country to visit in his international diplomatic tours. During this visit, he was personally received by President Xi Jinping, signaling the harmonious relationship between the two nations.

Nevertheless, Prabowo has not neglected Indonesia’s relationship with the United States. With the U.S. being the second country he visited after China, Prabowo’s actions are seen as sending a message to Washington to pay greater attention to Indonesia. Another surprising move was Prabowo’s signing of the Beijing Joint Statement, which raised eyebrows in Western countries. This bold step demonstrated his dual approach—leveraging Indonesia’s partnership with China to gain bargaining power and secure greater engagement from the United States.

However, Indonesia’s closer ties with China are not without challenges. Beijing’s unilateral claims over the South China Sea pose a threat to Indonesia’s sovereignty. While Indonesia de facto rejects these claims, the government’s response is viewed as ambiguous, as it has refrained from taking a firm stance or decisive action. Despite the clarity from Foreign Minister Sugiono, Prabowo’s announcement in Beijing initially suggested the possibility of joint development in disputed waters, which some observers saw as a potential shift in Indonesia’s longstanding position.

While Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has now emphasized that no new joint development areas are being created, the ambiguity surrounding the agreement still leaves room for interpretation and raises questions about how Indonesia will navigate its complex relationship with China moving forward.

Indonesia’s response to the South China Sea is a critical test of its foreign policy. To protect its territorial rights against China’s growing pressure, Indonesia must reaffirm its commitment to international law, strengthen defense capabilities, and solidify regional alliances, especially within ASEAN. Any softening of Jakarta’s stance could undermine trust in ASEAN and weaken its negotiating position.

This soft position could also impact its relations with global powers like the U.S. and Japan, which support its maritime claims. A more flexible approach could damage Indonesia’s credibility and compromise recent agreements like the EEZ deal with Vietnam.

To navigate these challenges, Indonesia should reaffirm its commitment to UNCLOS, protect its EEZs, reject China’s ten-dash line, and strengthen ties with regional partners like India and South Korea. Enhancing defense, especially in the Natuna Sea, is essential for asserting sovereignty.

Prabowo’s pragmatic foreign policy toward China seeks to balance economic ties while avoiding full alignment. However, this strategy raises concerns about potential Chinese influence on Indonesia’s sovereignty. Indonesia’s ability to maintain independence amid rising great power competition will depend on how effectively Prabowo manages these relationships. If successful, this approach could strengthen Indonesia’s global standing; if not, it risks compromising sovereignty.

Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat is the Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS).