Global debates about China’s rise often revolve around military flashpoints or ideological rivalry. Far less attention is paid to how societies in influential middle powers actually perceive Beijing’s growing role. Indonesia—home to more than 270 million people, Southeast Asia’s largest economy, and a country with a long tradition of non-alignment—offers an especially revealing case.

A new public opinion survey released last month shows that Indonesians view China neither as a looming menace nor as a trusted patron, but as a source of opportunity that must be carefully managed.

Economy First

The survey was conducted by the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), one of Indonesia’s leading independent policy research institutes, known for its work on political economy and governance. Taken a year after President Prabowo Subianto assumed office and shortly after Indonesia joined BRICS, the survey provides a timely snapshot of public attitudes at a moment of political transition and intensifying global competition.

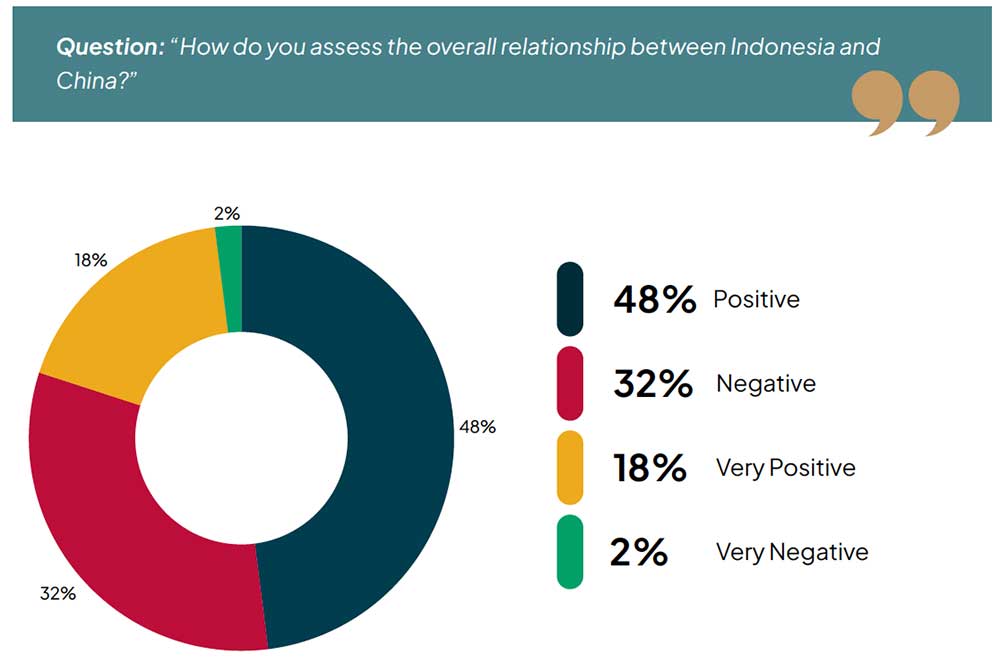

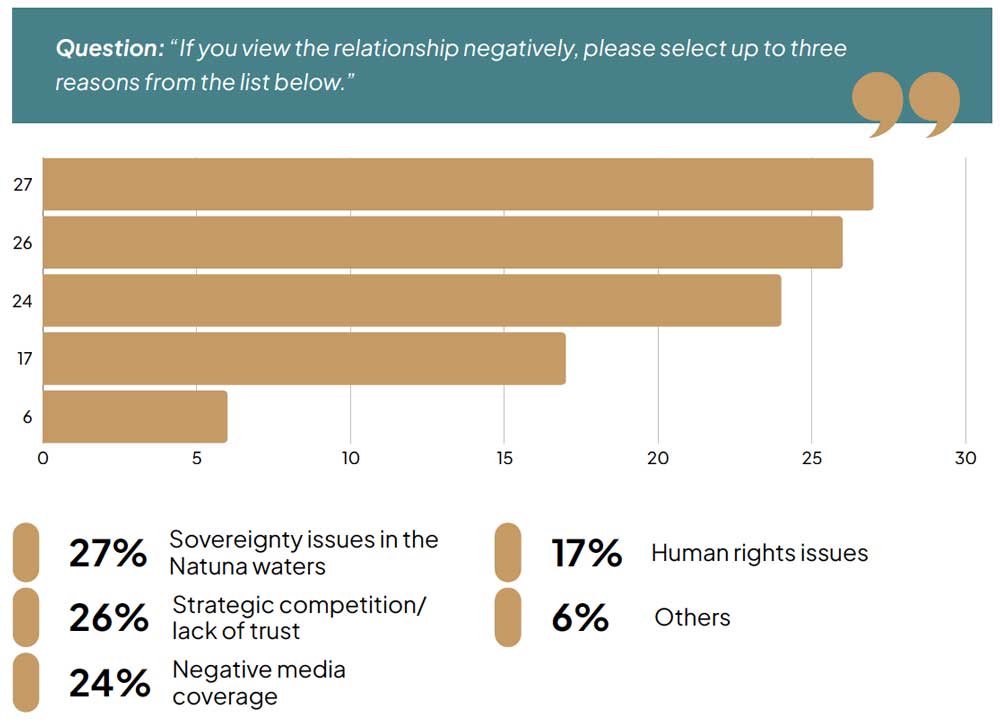

At a headline level, Indonesians appear broadly comfortable with China. About two-thirds of respondents characterize the bilateral relationship positively, while outright hostility remains limited. This finding stands out at a time when skepticism toward China is growing in many parts of the world. Yet positive sentiment should not be mistaken for deep trust or ideological alignment. What emerges instead is a distinctly pragmatic worldview.

2025 China-Indonesia Survey: Insights into Indonesian Perception of China

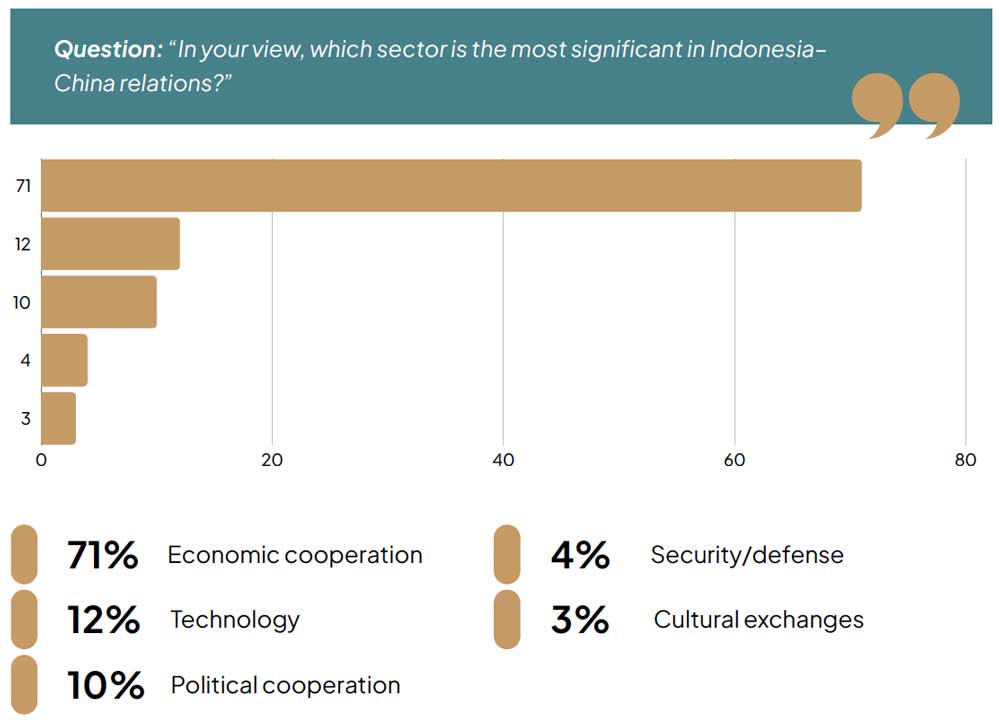

Economic considerations dominate nearly every aspect of how Indonesians think about China. Asked what defines the relationship, respondents overwhelmingly pointed to trade, investment, and development cooperation. Technology collaboration followed at a distant second. Political coordination, security cooperation, and cultural exchange barely registered. In public perception, China is not a strategic ally or a values-based partner; it is an economic actor that delivers tangible outcomes.

That same logic shapes views of President Prabowo’s close engagement with Beijing. Nearly all respondents believe he maintains a close relationship with China, yet most see this as beneficial rather than risky. The perceived gains are concrete: expanded economic opportunities, stronger diplomatic leverage, and greater room to maneuver amid rivalry between major powers. Concerns about national sovereignty or reputational costs exist, but they are clearly secondary.

Indonesia’s enthusiastic support for joining BRICS follows a similar pattern. Approval is nearly universal, driven not by symbolism or ideological affinity but by expectations of access—new markets, alternative sources of financing, and reduced dependence on Western-led institutions. BRICS, in the public imagination, is a practical instrument rather than a geopolitical statement.

Views on China’s role in Indonesia’s energy transition further reinforce this instrumental mindset. Large majorities believe China can be a reliable partner, citing employment creation, access to green technology, proven project delivery, and affordable funding. Environmental leadership or shared climate norms matter far less than whether projects generate jobs and arrive on schedule.

Conditional Trust

Yet enthusiasm consistently comes with conditions. Interest in Chinese electric vehicles, for example, is divided. While a slim majority is open to purchasing them, many remain hesitant due to concerns over charging infrastructure, after-sales service, and long-term reliability. Support exists, but it is contingent on performance rather than brand or national origin.

Education preferences tell a similar story. China now ranks as the most popular destination for overseas study among respondents, surpassing traditional Western choices. The reasons, however, are straightforward: scholarships and affordability. Cultural attraction or political affinity plays a minimal role. China is appealing because it is accessible.

Source: Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS)

2025 China-Indonesia Survey: Insights into Indonesian Perception of China

Perhaps the most revealing finding emerges when Indonesians are asked to identify their preferred primary partner. China leads—but only narrowly, with about one-third support. The majority favors a mix of Western countries, regional neighbors, or diversified engagement. This reflects a deeply ingrained instinct to avoid overdependence on any single power, echoing Indonesia’s long-standing foreign policy principle of strategic autonomy.

The limits of public trust become especially clear in the security domain. When respondents consider preferred sources of defense equipment, Russia ranks first, while China lags behind. This suggests that economic cooperation with Beijing does not easily extend into strategic or military confidence. Two decades after Indonesia and China formalized a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” public perceptions still see the relationship as largely commercial rather than strategic.

Bounded Alignment

Methodological caution is warranted. As an online survey, it largely reflects the views of urban, highly educated, and Java-based respondents, with rural, lower-income, and outer-island communities underrepresented. While it cannot be taken as fully representative of all Indonesians, it remains valuable for understanding how important, digitally connected segments of society think about China.

For China, the message is clear: economic visibility generates goodwill, but it does not automatically translate into strategic loyalty. For the United States, the challenge is different. American influence appears muted not because of hostility, but because its economic presence is less tangible in everyday Indonesian life. And for Indonesia itself, the findings underscore both achievement and constraint. Pragmatic engagement with China has delivered real benefits, but it rests on conditional support and persistent diversification.

Source: Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS)

2025 China-Indonesia Survey: Insights into Indonesian Perception of China

Indonesia’s approach to China, as reflected in public opinion, is careful, transactional, and deliberately bounded. In an era increasingly framed as a choice between rival camps, Indonesians appear determined to keep their options open—welcoming opportunity without surrendering autonomy. Whether that balance can endure as global pressures intensify remains an open question, but for now the public mood is unmistakably clear-eyed.

This article was co-authored by Yeta Purnama, a researcher at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), and Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at CELIOS.