This article is co-authored by Yeta Purnama, a researcher at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), and Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at CELIOS.

The China-Indonesia Media Forum that took place in Beijing in early September illuminated a complex question in contemporary media diplomacy: Can traditional partnerships still exert influence in a landscape now dominated by TikTok and real-time social platforms? As Beijing intensifies its media engagement with Indonesia, questions linger about the effectiveness of this strategy in an era defined by fleeting attention spans and digital saturation.

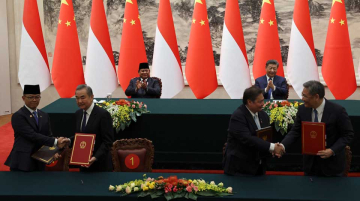

This year’s forum, following its 2023 debut in Jakarta, assembled media majors such as the state-run Xinhua news agency alongside Indonesian counterparts like Antara National News Agency, the digital news platform Kumparan, and the English-language daily The Jakarta Post. Indonesia’s ambassador to China, Djauhari Oratmangun, framed the cooperation as a strategic instrument—beyond mere information exchange, a potent lever for shaping perceptions and strengthening bilateral ties.

Strategic Underpinnings and Aspirations

China’s media efforts in Indonesia reflect a wider regional ambition, positioning media as a vehicle to embed Beijing’s narratives. With Indonesia at the heart of Southeast Asia’s geopolitical and economic matrix, Chinese outreach aims to bolster themes of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), its “peaceful rise,” and regional development leadership.

The forum built on the momentum of previous engagements like the July event in Jakarta, “I Read China,” orchestrated by the Academy of Contemporary China and World Studies (ACCWS), a state-run think tank under the China International Communications Group (CICG). This meeting included media representatives, think tank scholars, and academics, co-hosted by Al-Azhar University and Sinolingua, a CICG publishing arm. It exemplified Beijing’s drive to embed its narratives through a multi-layered approach.

For Indonesian outlets, collaboration with Chinese media comes with dual-edged implications. Financial incentives may offer relief in a challenging economic landscape, but alliances risk perceptions of compromised integrity.

Despite robust investments, the tangible reach of these partnerships remains debatable. Indonesian media consumption has shifted to digital-first platforms, with over 70% of audiences now sourcing news through social media. This reality poses a formidable challenge to China’s traditional tactics. While state-backed ventures like Tiongkok dalam Layar (China on the Screen) bring cultural exchange to Radio Republik Indonesia, they struggle to capture significant audiences. The perception of such programs as overt propaganda undermines their impact.

The media landscape in Indonesia mirrors global trends, where platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram redefine content consumption. Grassroots digital influencers and real-time user engagement render state-driven content less compelling. Efforts such as Guangxi Radio and Television’s documentaries, showcasing Chinese economic contributions, often fail to compete with localized narratives more attuned to public sentiment.

The Logic of Persistence

Why does China continue these efforts despite limited success? One explanation is strategic patience—building media ties today could yield influence tomorrow as economic dependencies grow. Symbolically, these partnerships signal China’s unwavering commitment to soft power, framing it as a steady, benevolent force even when immediate results lag.

China’s approach is not an anomaly but part of a broader geopolitical playbook. Similar strategies are employed by global powers to shape public perception through state-sponsored media and international exchanges. However, China’s adoption of Content Sharing Agreements (CSAs) has distinguished its diplomacy, allowing Chinese narratives to seamlessly integrate into local reporting. This tactic, deployed effectively in Latin America and Africa, provides a model that China’s rivals in the U.S., Asia, and Europe have yet to emulate with comparable success.

For Indonesian outlets, collaboration with Chinese media outlets comes with dual-edged implications. Financial incentives may offer relief in a challenging economic landscape, but alliances risk perceptions of compromised integrity. Partnerships that edge too close to promoting foreign agendas can erode trust, particularly as audiences grow increasingly discerning about media independence.

Indonesia’s balancing act between U.S. and Chinese relations further complicates these partnerships. Whether they reinforce or weaken Indonesia’s media ecosystem is an open-ended question.

Ambassador Oratmangun hinted at a potential pivot: embracing influencers to revitalize media influence. Past trials, such as the Chinese embassy’s facilitated tours featuring figures like former Miss Indonesia Alya Nurshabrina, suggest this strategy’s mixed outcomes. While these initiatives have showcased softer, people-focused narratives, their efficacy in overcoming ingrained skepticism remains unclear.

Conclusion

China’s media diplomacy in Indonesia, characterized by ambition but tempered by limited results, reflects the complexities of influence in the digital era. The strategy underscores both the persistence and adaptability required to engage in a rapidly shifting media landscape, revealing soft power’s nuanced dance between tradition and innovation. Whether Beijing’s investments will translate into the sway it seeks or falter amid Indonesia’s evolving media appetite is a question that will unfold in the coming years.