By Amanda Chen

Building on our previous analysis of China’s official position and expert debate on the Iran–Israel War, this edition of the ChinaMed Observer examines how the conflict has shaped Israeli analysts’ perceptions of China’s role in the Middle East. Even prior to the outbreak of hostilities, Israeli media had voiced mounting concern over Beijing’s ties with Tehran, devoting considerable coverage to reports of alleged Sino-Iranian military cooperation. These anxieties persisted during and after the “Twelve-Day War” (June 13–24), despite China’s denial of the allegations.

This predominantly negative media portrayal of China is illustrative of the lingering feeling of estrangement toward China within Israeli public opinion. At the same time, the perceived limitations of China’s partnership with Iran seem to have led several Israeli China and security experts to view the conflict as a potential turning point for reassessing bilateral relations with Beijing.

General Suspicion: Is China Arming Iran?

In early June, in the weeks leading up to the war, Israeli news outlets widely circulated a report from The Wall Street Journal alleging that, even in the shadow of the nuclear talks, Tehran had purchased from Beijing thousands of tons of military components – including rocket propellants used in ballistic missile production – to rebuild military systems previously damaged by Israeli strikes in October 2024. It was speculated that parts of these shipments might be destined to Iran-backed groups in the region, such as the Houthis in Yemen. These reports raised widespread concern about Tehran’s rearmament and the significance of alleged, through unverified, Chinese support.

Following the outbreak of war, suspicion of possible continued Chinese support for Iran was raised again by Western media and reported by Maariv when cargo flights departing from China had mysteriously disappeared from the radar near the Iranian border. As Head of Research at ChinaMed, Andrea Ghiselli observed, these flights sparked considerable scrutiny “because of the expectation that China might do something to help Iran.” The rumor was later debunked by Tuvia Gering, a visiting researcher at the Israel-China Policy Center of the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), who explained to Maariv that the planes had merely stopped over in Turkmenistan and belonged to Luxembourg cargo airline Cargolux, adding that “beyond simple logic – it is hard to believe that a major European cargo company would be used to transfer advanced weapons from China to Iran.” Nonetheless, the expert cautioned that while the likelihood of Sino-Iranian military cooperation may be low, it “should not be dismissed, and must be closely monitored.”

This line of reporting persisted even after the war formally ended with a U.S.-brokered ceasefire on June 24. For instance, Israeli media framed the visit of Iranian Defense Minister Aziz Nasirzadeh to China on June 25, where he attended the conference of defense ministers of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, as further evidence of alleged direct Chinese support for Iran’s rearmament.

Yair Amar, political correspondent for the right–wing outlet Srugim, reported that Nasirzadeh’s visit was likely to be a procurement campaign to acquire new air defense systems and even the Chinese J-10 fighter jet, believed to be based on the cancelled Israeli Lavi aircraft, which Egypt had also intended to acquire. Analysts emphasized that the J-10 fighter jet, which demonstrated notable effectiveness during Pakistani aerial engagements against India in early May, could significantly challenge Israel’s air superiority in the Middle East should it be acquired by regional states. Middle East Eye, citing anonymous Arab officials, reported that both the U.S. and its Arab allies were aware of Iranian rearmament efforts, further alleging that Tehran pays for missiles with oil shipments.

Experts’ Reaction: There is Still Room for Cooperation

Amid overwhelming suspicion in the Israeli media landscape regarding Chinese military support for Iran, Israeli experts and diplomats offered different and more nuanced views. While some interpreted the reports as enduring proof of Sino-Israeli estrangement, most adopted a more cautious tone, urging a reassessment of Israel’s China policy. These experts noted that ultimately, despite the media coverage, Beijing’s diplomacy during the war did not directly harm Israel and might even turn to Tel Aviv’s advantage if managed well.

One of the most critical views of China was expressed by Israel’s Ambassador to Washington, Yechiel Leiter, who strongly criticized alleged Sino-Iranian military cooperation. In an interview for The Voice of America, later republished by Ynet, the ambassador warned that Israel should prioritize preventing China from helping Iran rebuild its missile program, noting that despite its interest in “maintaining good relations with the Chinese people,” Israel cannot agree to China “working hand in hand with a country that openly threatens to destroy us.”

Nadav Eyal, columnist for Yediot Ahronot, echoed these concerns, opining that “the issue [of Chinese military cooperation with Iran] is very troubling and may have strategic implications,” despite official sources claiming that Beijing “did not confirm the allegation.” For his part, Yoram Evrom, an Associate Professor of Political Science and Chinese Studies at the University of Haifa, observed that even if China was taking the risk to help Iran, it would probably supply equipment classified as “dual-use” to go under the radar, because fundamentally, Beijing does “not risk its interests for others.”

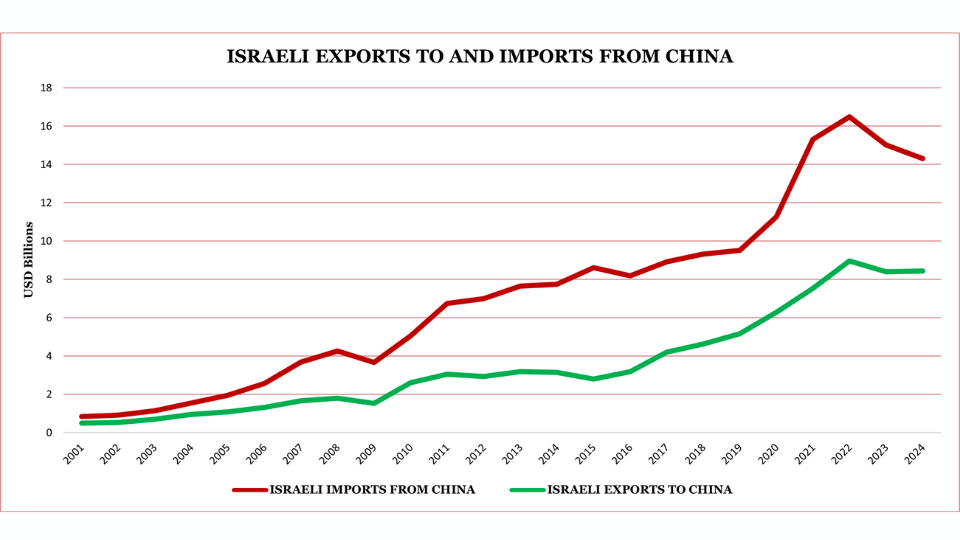

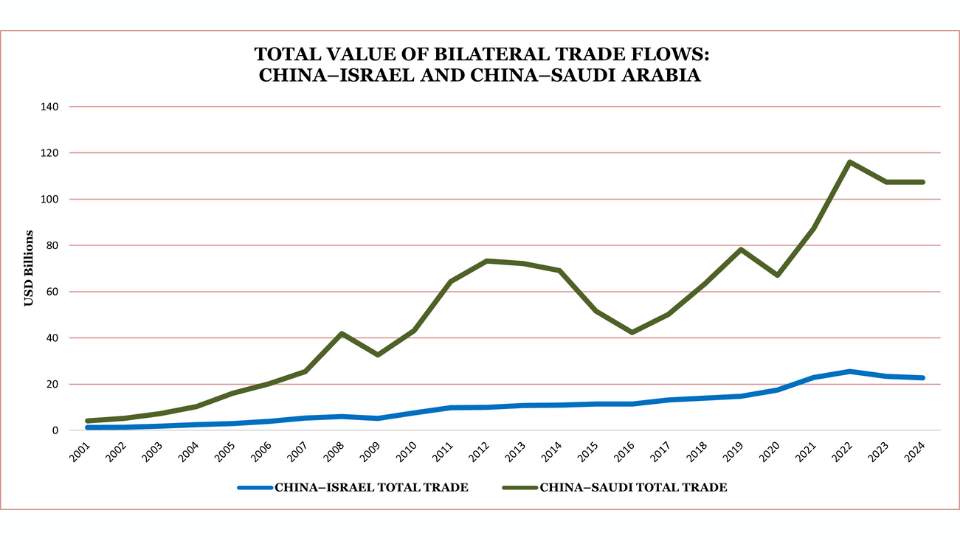

Unlike her U.S.-based counterpart, Israel’s Consul General to Shanghai, Ravit Baer, conveyed a more pragmatic message in an interview with Bloomberg TV that later appeared on Maariv. She directly appealed to Beijing to restrain Iran’s rearmament, stating that “China is the only one capable of influencing Iran,” but that as long as China continues to buy oil from Iran, it will be difficult to curb Tehran’s aggressive policy. At the same time, she warned that an Iranian air force strengthened by Chinese J-10 aircraft would not only represent a threat to Israel, but also to other Middle Eastern states such as Saudi Arabia, a country vital to Beijing’s regional interests and ambitions. Nonetheless, while acknowledging the political divergence between Tel Aviv and Beijing, she underscored the robust bilateral trade figures as proof that:

“Even if we disagree politically, that doesn’t mean we can’t cooperate. There is still a positive dialogue.”

Several analysts echoed Baer’s perspective, emphasizing how Beijing had pressured Tehran not to close the Strait of Hormuz, despite the Iranian parliament unanimously endorsing the measure on June 22, shortly after the U.S. strikes on Iranian nuclear sites. On June 23, Israeli media underscored Beijing’s involvement, reporting that Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) had called his Iranian counterpart Abbas Araghchi “to prevent even more severe economic damage to global trade.” Amatzia Baram, a professor emeritus of Middle East history at the University of Haifa, explained that China, in particular, had a strong interest in preventing the war from escalating as it “very much needs Iranian oil” and would be “the first to suffer” from a disruption in supply.

While some analysts attributed China’s pressure on Iran primarily to economic considerations, others contended that this episode revealed “cracks in the anti-Western axis,” given that neither Moscow nor Beijing offered Tehran substantial support during the war. Notably, China refrained from attempting to isolate Israel at the United Nations as some had expected. Galia Lavi, Director of the Israel-China Policy Center at the INSS, argued that Beijing’s measured rhetoric since Israel’s “preemptive strike” on June 13 reflected both China’s caution to avoid entanglement in the conflict and its consistent opposition to Iran developing nuclear weapons, which Beijing sees as a scenario detrimental to its own strategic interests in the region. She added that “this balancing policy shows that Beijing does not see itself as part of the Iranian axis,” but rather, that it strives to delicately balance its relationships with Iran, Israel, and the Arab states.

A Turning Point for Bilateral Relations?

In contrast to the harsh statements issued in the aftermath of Hamas’s attack on October 7, 2023, Chinese state media refrained from directly criticizing Israel during its war with Iran, limiting itself to condemning the violation of Iran’s sovereignty, while urging restraint and de-escalation. Beijing’s softer rhetoric toward Tel Aviv is a continuation of a trend that started last year, marked by the arrival of the new Chinese ambassador to Israel, Xiao Junzheng (肖军正). In early July, Xiao gave an interview to Israel Hayom in which he strongly denied allegations that China had provided military support to Iran, including the transfer of missiles and J-10 fighter jets. He dismissed such claims as misinformation, declaring that “a lie repeated 1000 times remains a lie.” Israel Hayom reporters agreed that, to some extent, the interview embodied “the change in Chinese tone toward Israel during the war.”

Doron Cucos, a researcher of international relations and East Asia and guest contributor at the Mitvim Institute, characterized China’s rhetorical shift and Israel’s military success against Iran as a “watershed moment” for reshaping Tel Aviv’s bilateral relations with Beijing. Cucos argued that Tel Aviv should seek alignment with Beijing on issues where their interests converge, “particularly on containing Iran’s nuclear ambitions and curbing regional instability.”

Geopolitics analyst Dr. Anat Hochberg-Marom also considered the war a turning point for China’s regional strategy: while Israeli and U.S. military strikes challenged and weakened Iran, they simultaneously heightened China’s dependence on Arab Middle Eastern oil exporters. As such, she encouraged Tel Aviv to seize the opportunity to “adopt a new, pragmatic foreign policy” toward China and strengthen relations with Beijing. Hochberg-Marom went as far as to argue that “amid mounting global criticism of Israel, the renewal of nuclear talks with Iran, and the unpredictable foreign policy of the President of the United States,” recognition from China could rehabilitate Israel’s image in the Global South, whereas Beijing for its part would enhance its image as a credible conflict mediator.

While closer Sino-Israeli cooperation was generally viewed as feasible and even desirable, most experts remained less optimistic about China’s potential role as a mediator. Dudi Kogan, writing for Israel Hayom, contended that the war and the American intervention underscored Washington’s enduring primacy as security provider in the Middle East.

Galia Lavi and Ori Sela from the Israel-China Policy Center at the INSS shared the same perspective, arguing that, against the backdrop of the conflict, “the region’s countries never expected more than rhetoric from China in the first place” as they “distinguish between China’s importance in economic and infrastructure matters from political-military issues, where they clearly rely on the United States.” Similarly, Roy Ben Tzur, a Research Assistant hailing from the same institution, added that, in light of China’s perceived diplomatic alignment with Israel’s adversaries, Beijing’s credibility as a mediator will remain compromised unless it “chooses to balance its positions and recognize the complexity” of the security threats facing Tel Aviv.

Conclusion

The Israeli media debate on China during and after the war with Iran revealed a notable shift in tone compared to the previous year, as documented in our report, China in the Shadow of October 7: Israeli Media Coverage of China in 2024. Although the extensive media coverage of Beijing’s alleged military support for Tehran reflected lingering estrangement toward China within Israeli public opinion, several China and security experts interpreted the conflict as an opportunity to reassess bilateral ties.

Among those publicly advocating for a rapprochement with China was Ravit Baer, Israel’s consul to Shanghai, who emphasized the importance of preserving bilateral trade relations, which “did not deteriorate significantly despite the conflicts since 2023,” and whose continuity may assist in sustaining Israel’s economy during wartime. The reemergence of a more pragmatic outlook toward China among some Israeli experts, however, was shaped not only by economic considerations but also by diplomatic factors, in particular, the efforts of China’s new ambassador to Israel, Xiao Junzheng (肖军正), and Beijing’s subsequent softening of its rhetoric toward Tel Aviv.

Nevertheless, trade continues to constitute the central pillar of Sino-Israeli relations. Both sides are thus likely to preserve and cultivate channels for cooperation, where the more immediate challenges lie in navigating the economic uncertainties produced by U.S. President Donald Trump’s volatile tariff regime and the broader dynamics of U.S.-China competition. Yet resilient economic ties and diplomatic considerations have not translated into a shift in Israeli public perceptions of China. Overriding concerns about national security, coupled with enduring skepticism rooted in China’s initial response to the current war in Gaza and its ties with Iran, remain present, sentiments that are also shared by most Israeli experts. Consequently, while a growing number of analysts support expanding cooperation with China, few extend that optimism to Beijing’s much-discussed aspirations to act as a mediator in the Middle East.

Amanda CHEN (陈心怡) is a Research Fellow at the ChinaMed Project. She is also a graduate of the Sciences Po-Peking University Dual Master’s Degree in International Relations and Diplomacy and holds a B.A. in Middle Eastern Studies from SOAS University of London. Her research interests include Chinese diplomacy in the Middle East and broader China-Middle East relations.