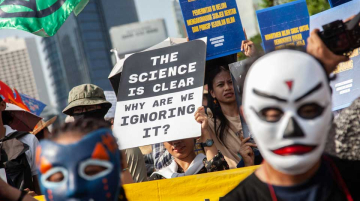

Tropical forests around the world are vanishing fast. Logging, mining, and industrial agriculture continue to raze the world’s most carbon-rich ecosystems, accelerating the climate crisis and displacing the people who have protected these forests for generations. Efforts to halt deforestation have largely failed—not because the science is unclear, but because the money flows in the wrong direction.

We still reward destruction more than preservation.

A new climate finance mechanism, the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), aims to change that. It proposes a $125 billion global endowment to pay countries—not for promises or pledges, but for measurable, verified forest protection.

If a country keeps deforestation below a set threshold, it receives a share of the investment returns. If it doesn’t, the money stops. At least 20 percent of those funds must go directly to Indigenous peoples and local forest communities.

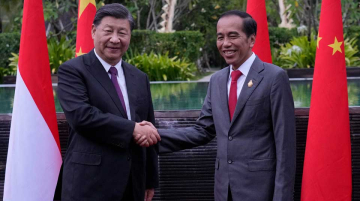

The plan is bold, and it’s built for accountability. But whether it works will depend on who shows up—and how. Two countries that could play decisive roles in the months ahead are China and Indonesia.

Neither has a spotless record. In fact, that’s exactly why their participation matters.

China has so far offered considerable political support for the TFFF. Its finance minister recently told Brazilian officials the initiative is a priority. But China’s climate finance track record abroad is modest.

Unlike the U.S. and European Union, which have long been pressed to pay for climate damages, China positions itself as part of the Global South—not a historical polluter with financial obligations. Its climate investments are framed as voluntary partnerships, not compensation.

And when it comes to enforcing environmental standards on Chinese companies operating overseas—in logging, fishing, or mining—Beijing has been largely silent.

Still, China has the economic and diplomatic clout to help shape climate finance in a more just and effective direction, if it chooses to engage seriously. The TFFF presents a rare opportunity: a performance-based model that doesn’t demand reparations, but does demand results.

Indonesia, home to the world’s third-largest tropical forest area, is both a potential beneficiary and a governance board member of the TFFF. It has committed to reaching net-zero deforestation by 2030—a laudable goal. But on-the-ground reality tells a more complicated story.

Despite a patchwork of reforms, Indonesia’s environmental enforcement remains weak, with corruption, illegal operations, and industrial expansion undermining progress. The country’s nickel mining boom, in particular, has devastated landscapes with little accountability.

So why should anyone trust Indonesia to help steer a global forest protection fund? Not out of blind optimism—but because the alternative is worse. Without the involvement of large, forested countries like Indonesia, the TFFF will struggle to reach scale.

And without mechanisms that channel money to communities on the frontlines, no global solution can succeed. Indonesia’s participation can be valuable—not because it is a model, but because it’s a test case for how better safeguards, incentives, and scrutiny can push flawed systems in the right direction.

Together, China and Indonesia have the chance to make this new model work—not by leading with grand speeches, but by engaging with hard constraints. China could help fund the facility and push for transparency in how payments are managed. Indonesia could help define how communities receive support, how deforestation is monitored, and how accountability is enforced. Neither country needs to be perfect. But both need to be present—and pressure will be essential from civil society, other governments, and the climate movement to keep them honest.

Time is short. The TFFF is expected to launch formally at COP30 this November in Brazil. The fund’s rules, governance, and financing structure are still in flux. What happens now will determine whether this becomes just another climate announcement—or something that actually shifts incentives on the ground.

This is not a test of who has the best track record. It’s a test of who’s willing to do better. If China and Indonesia step forward—not as heroes, but as serious participants—they can help prove that tropical forest protection isn’t just aspirational. It’s operational.

This article was co-authored by Yeta Purnama, a researcher at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), and Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at CELIOS.