By Jared Bissinger

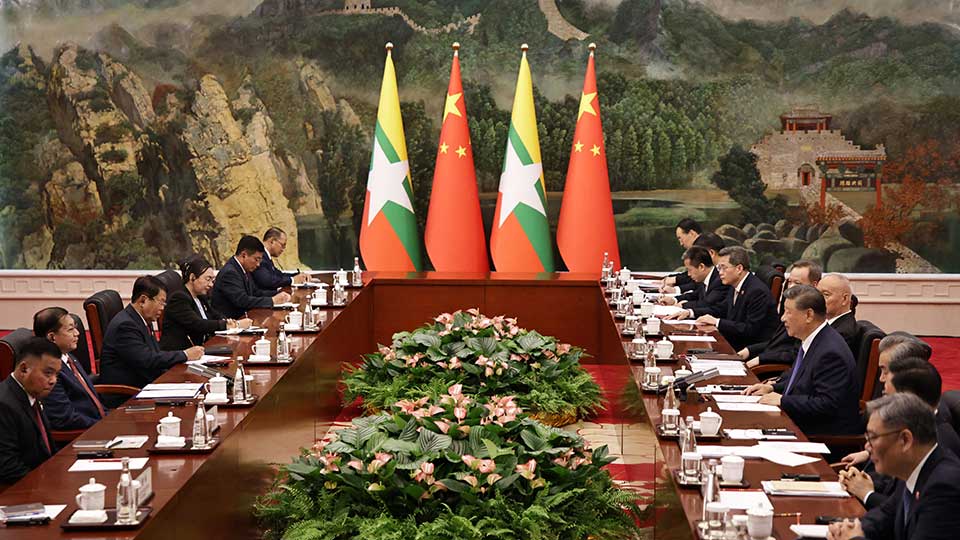

In the last year, China has increasingly used its economic leverage in Myanmar to tilt the scales towards the military’s State Security and Peace Commission (SSPC), helping them to regain territory and re-exert economic control. China has done this by combining its economic heft and proximity to Myanmar with a policy of fostering economic connections with both state and non-state authorities, then leveraging these to its advantage.

Western countries, on the other hand, have adopted some sanctions but continue trading with the SSPC-controlled state. This is despite the SSPC’s numerous changes to the trading system, which have given it extraordinary control and benefits.

The result is that the West’s economic engagement with Myanmar is indirectly undermining its political objectives and aid dollars. This is the key reason why China has been increasingly influential in Myanmar while Western countries have been sidelined.

China’s approach to Myanmar focuses largely on protecting its interests, many of which are economic. These include ensuring access to natural resources like rare earths and keeping other countries from buying them, and protecting infrastructure projects such as the Myanmar-China oil & gas pipelines. China also wants to ensure continued and stable trade in goods, so it trades with the SSPC as well as non-state authorities, through a range of unofficial checkpoints.

China has repeatedly leveraged its economic links to shape the actions of non-state authorities, despite a stated policy of non-interference. It has halted trade, closed borders, cut off essential services, and clamped down on financial services. These are part of China’s so-called “five-cut policy” against non-state groups: cutting supplies of internet, fuel, electricity, food and essential commodities to force them into submission.

There are many examples of this approach. In July, China threatened to stop buying rare earths from mines in Kachin Independence Army (KIA)-controlled areas unless they stopped trying to seize Bhamo. China cut off electricity, internet and water to Kokang areas to pressure the MNDAA not to attack further than Lashio and not to align with the NUG, which China perceives as aligned with the West. China pressured the United Wa State Army in Northern Myanmar to stop providing arms to other groups by freezing assets and sealing border crossings.

China has also used its economic leverage with the SSPC. Most notably, it pushed them to allow a joint venture security company through which China could use armed Chinese security guards to protect its cross-border investments. China pressured the Myanmar military to expedite its deep-sea port in Kyaukphyu.

In the short term, China’s approach has proven effective. Conflict in Northern Shan has subsided, and trade looks increasingly likely to restart. However, China’s moves do little to advance durable peace or stability in Myanmar. This may be the point, however. China’s goal, according to the U.S. Institute of Peace, is to keep Myanmar as “a weak and fragmented country with just enough stability to protect Beijing’s strategic economic interests”.

Western countries have taken a much different approach. Compared to China, they have more limited economic interests in and economic engagement with Myanmar. Instead, they have focused more on issues such as development and peace. The Trump administration has not yet released a policy on Burma, but under the Biden administration, the US framed its interests around promoting a “peaceful, prosperous, and democratic Burma.” The EU frames development cooperation with Myanmar around priorities including peace and governance, and sustainable livelihoods.

While Western countries have adopted some financial sanctions on Myanmar, they have not significantly changed their trade engagement with it. However, Myanmar’s military has fundamentally changed their trade and financial systems, adopting draconian trade licensing, capital controls, foreign currency surrender requirements, and a multiple exchange rate system. A number of the military’s policies directly contradict important parts of the international trading order. Yet Western countries have done little in response to this.

These changes thus enable the military regime to capture significant benefits from trade and financial flows, and control which individuals and business can access forex and trade licenses. This system is integral to keeping the military in power.

For Western countries, this presents an uncomfortable truth: their economic approach to Myanmar is undermining their political goals and support for the pro-democracy movement.

Western governments often justify this by arguing that trade is vital to the livelihoods of millions of Myanmar people. Indeed, millions of Myanmar people depend on trade and work in export-oriented sectors. However, in recent years, declining incomes and increasing poverty — largely driven by the military’s economic policies — raise doubts about whether trade under the SSPC is really helping Myanmar people. This is important: raising living standards and ensuring full employment are primary justifications for the global trading system. In Myanmar, though, the SSPC’s post-coup policies make these goals tough to achieve.

In the short-term, China’s approach has been more effective at achieving its goals. The key difference is that China’s economic engagement, especially trade relations, with non-state authorities is a vital tool to advance its interests in Myanmar. It provides a leverage point that China has repeatedly exploited. For Western countries, the shortcomings of their approach to Myanmar are increasingly clear. A fundamental rethink is needed if they hope to advance their goals in Myanmar.

Jared Bissinger is a Visiting Fellow with the Myanmar Studies Program at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, and the Research Lead at Catalyst Economics.

This article was originally published on the Fulcrum website and was reprinted here with permission of the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.