Over the past decade, China positioned itself as a leader in copper refining, accounting for more than half of global capacity. Its strategy designed to secure control over key critical minerals meant to power everything from clean energy grids to electric vehicles, defense equipment, and construction industries paid off. But that strategy is now showing cracks.

Smelters across China and its overseas ventures, whose business is to heat copper ore and turn it into refined products used in different industries, are shutting down or suspending operations due to a deepening shortage of copper concentrate, the raw material needed for refining.

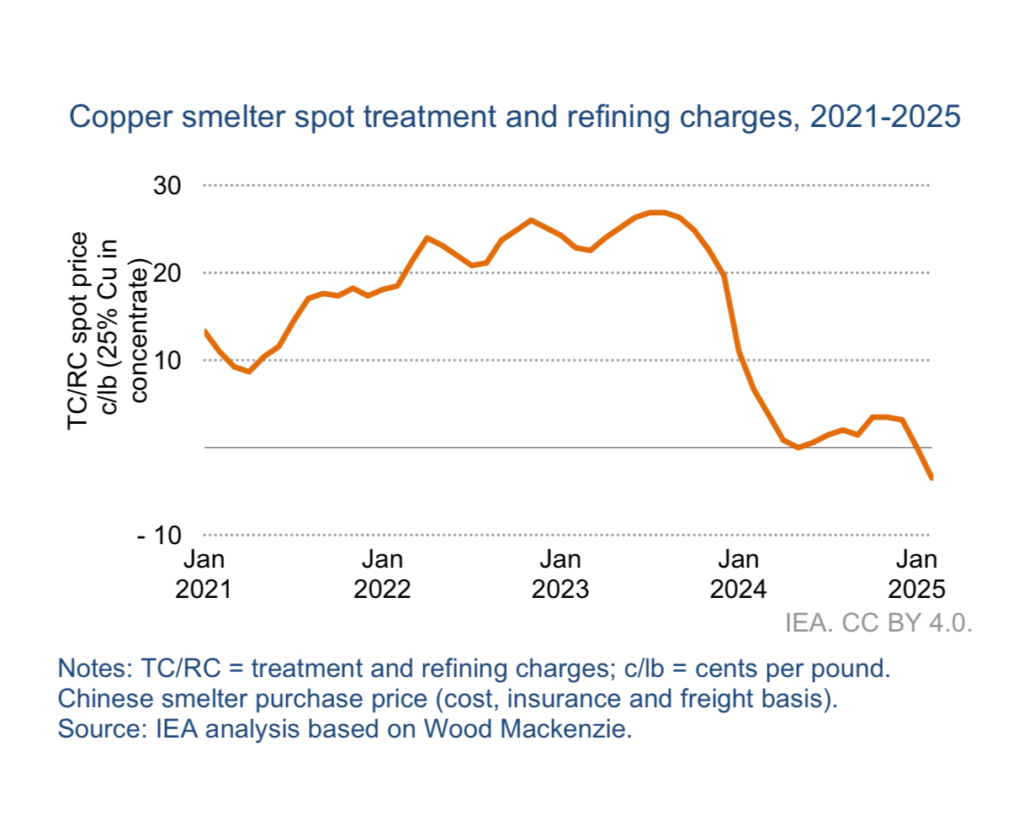

Increasingly, there is a growing mismatch between smelting capacity and mine output, which has sent processing fees into negative territory, threatening the viability of these massive investments.

The Smelting-Mining Mismatch and Collapse in Smelting Fees

Copper is indispensable to modern infrastructure, as it is used extensively in power grids, construction, transportation, defense, and renewable technologies such as solar panels and wind turbines.

China’s ambitious green energy expansion has been a major driver of copper demand. The surge in China’s grid network investments was the primary driver of copper demand growth between 2022 and 2024.

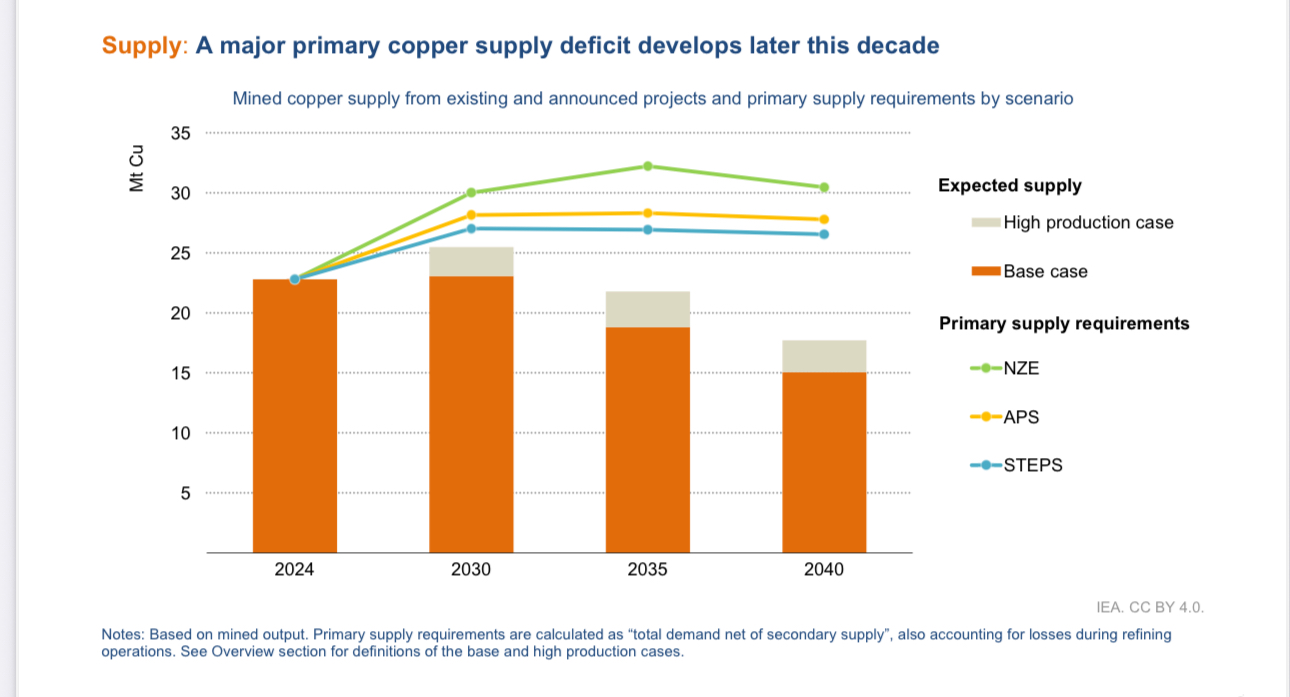

Despite strong copper demand from electrification, the current copper mines project pipeline points to a potential 30% supply shortfall by 2035 due to declining ore grades, rising capital costs, limited resource discoveries and long lead times.

However, this demand surge has not been matched by sufficient growth in mine output.

Globally, the capacity to smelt copper ore and turn into copper cathode through a process of separating ore from other elements to produce finer copper has increased between 2023 to 2024 by 5%.

Copper treatment charges which are typically fees for processors, have plunged deep below zero. A Chilean copper miner Antofagasta Plc proposed negative charges for contracted supplies to Chinese smelters.

In May, the price charged by smelters to refine fell to an unprecedented minus $45 per tonne according to Fastmarkets. This has made some smelters to operate at a loss, with processing fees so low they no longer cover costs

However, to keep copper supply contracts, it appears some Chinese smelters accept unprofitable terms just to secure feedstock given that they have long term contracts with buyers. It appears that closing smelters can be even more costly than running at a loss given that they have high fixed costs.

Therefore running with negative profit margin is a long term strategy especially if they expect prices or fees to normalize.. However should copper mine output remain at the current state, the smelters will be forced to shut down.

In March, the Anglo-Swiss multinational mining and commodity trading company Glencore shut down its Pasar smelter in the Philippines, citing deteriorating market conditions. A Chinese mining giant, Sinomine Resource Group operating in Namibia, suspended operations at the Tsumeb copper smelter, one of the few facilities in the world capable of processing rich copper ores, which exporters from Chile, Peru, and Bulgaria supplied.

Chinese Smelters in Crisis Mode

Within China, particularly in the copper-rich provinces of Jiangxi and Yunnan, smelters are scaling back operations, pausing production, or turning to recycled scrap as an emergency measure. Many smaller refiners are operating well below capacity or shutting down entirely.

Despite strong global demand for copper, mine output is lagging.

In Chile and Peru, the world’s top copper-producing countries, production has declined, and ore grades have decreased. Similarly, Buenaventura, one of Peru’s largest mining firms, has had to delay a $2.77 billion copper project in Algarrobo, in the northern part of the country, due to community concerns over water access.

According to Skarn Associates, approximately 7% of the global copper supply is at risk of disruption from floods or droughts in 2024, a figure expected to increase by 30% by 2030. The result is a global copper ore crunch, choking smelters and raising alarm over long-term supply security.

A Long Road to Recovery

There’s no quick fix. Besides falling production, the average timeline from copper discovery to production is 17 years. This means that unless mining output is dramatically ramped up and fast, smelting overcapacity will continue to destabilize the market for the foreseeable future.

Source: International Energy Agency 2025

In the short term, more shutdowns may be inevitable. Industry players will either have to scale back smelting capacity or aggressively invest in new mining projects.

Ultimately this will impact copper producing countries like Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) building smelting facilities to capture more benefits from their copper resources.

The DRC, the world’s second-largest copper producer, is continuing to build smelters. The Kamoa-Kakula Copper smelter will be commissioning a major new on-site smelter in September this year, while Zambia’s Lualaba Copper Smelter (LCS) is expanding its capacity with investment from China Nonferrous Mining Corporation, a leading Chinese copper producer. However, there is a risk that these countries are investing heavily in capacity without doing the same to match the supply of copper ore. The result will be stranded assets, job losses, and revenue for governments.

To address the risk, governments seeking to industrialize must ensure they have sufficient ore or rather pursue regional partnerships with countries with significant reserves to ensure the supply of copper ore. Otherwise, investments in smelting facilities may end up as costly white elephants.