Last week’s China-Africa Economic and Trade Expo (CAETE) in Changsha, Hunan province drew very little press attention, but it gave a glimpse of the growing centrality of agricultural trade to the Africa-China relationship. The event delivered 176 new project deals worth $11.39 billion. The number was up by almost half, while the value of the deals only increased by 10.6%.

This seems to indicate a greater number of smaller deals than in 2023, which could mean that more (relatively) small-scale African producers are being pulled into Chinese trade for the first time. This raises new possibilities for a relationship that is still too often defined by mining.

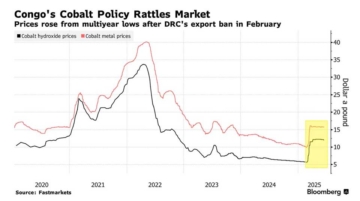

The global boom for transition minerals has put adding value to mining and extractives at the heart of Africa-China conversations. Important as that is, it faces significant challenges.

A key barrier is the industrial capacity and state support within China – beating the China price will always be a challenge. And even the most robust value-addition strategies can’t overcome the inherent violence of mining: some land will always be dug up, some people displaced, some water poisoned.

At Changsha, it was announced that China cut all tariffs on imports from 53 African countries (excluding Eswatini, which maintains relations with Taiwan). That will likely boost more extractive trade in the short run, but China has established Hunan province as an agricultural logistics hub and CAETE points to a future where farming is at least as important as mining to the Africa-China relationship.

But the simple removal of tariffs isn’t enough to make this shift. As exporters like Kenya have learned, China’s non-tariff barriers are a significant hurdle. These include complex phytosanitary rules guarding the People’s Republic against crop-borne invaders.

Jumping these hoops requires a trained bureaucracy and a set of refrigeration and storage facilities frequently out of Africa’s reach. This year’s Changsha Declaration following the expo directly addressed these barriers:

“For the least developed countries in Africa, on top of the zero-tariff treatment for 100 percent tariff lines announced at the 2024 Beijing Summit of FOCAC, China will roll out measures on market access, inspection and quarantine, and customs clearance to boost trade in goods, enhance skills and technical training, and expand the promotion of quality products.”

This measure increases African countries’ chance to make it on to the first rung of the agricultural trade ladder. It comes at a moment of opportunity: China is rapidly diversifying its sourcing of agricultural products to avoid its exposure to imports from the United States.

The result has been that purchases of commercial crops like corn and soybeans from agri-industrial giants like Brazil are going through the roof, while the U.S. agricultural heartland is feeling the squeeze.

In theory, Africa could get into this game. African leaders have long touted the continent’s land and water resources as the possible base of the continent’s own mass agriculture industry.

But that comes with a significant risk. The model of industrialized single-crop agriculture driving Brazil’s corn exports to Chinese feedlots could be ruinous if it’s imposed as Africa’s only solution. While it could work in some cases, it could also wipe out knowledge and ecosystems, push more people off their land into under-resourced cities, and, with the high level of automation in some farming sectors, not even create that many jobs.

I recently spoke with a senior African official focusing on minerals who mentioned being struck by a question he was asked by a Chinese official: why is Africa so focused on adding value to high-tech minerals like cobalt when it still struggles to feed its own people?

In other words, we know how central food security and small-scale agriculture have been to Chinese development. Is there a way of putting them first in the development of African agriculture and then building an export economy on top of that? Is there a way of setting up logistics and market mechanisms to scale up and improve the existing ecosystem of small-scale farmers growing highly diversified crops suited to local environments and tastes and using that as a basis for both food security and an export economy?

The proliferation of smaller deals in Changsha could hint at such a solution. Africa has numerous environmental niches and food economies. A patchwork of small farmers putting out high-value crops like honey, saffron, and vanilla could be a counter-solution to the industrial agriculture that paved parts of Southeast Asia in palm oil plantations.

This is not an easy needle to thread, but I fear that if we ignore these concerns, the continent could repeat the mistakes of colonialism. We can’t build an economy for future generations while disregarding the people, the knowledge, and the food that’s already here. Value addition depends on seeing the hidden value in front of you. Once you do that, selling it in a repackaged form at a big fancy expo in Changsha becomes much easier.