Chinese President Xi Jinping just concluded his visit to Vietnam, Malaysia, and Cambodia. Even though the visit took place while the world still struggles to understand and cope with President Donald Trump’s policies of imposing tariffs worldwide, it should not be narrowly understood as China’s response to the trade war waged by the United States.

The trade war only increases the significance of the visit. For China and the three Southeast Asian countries, and indeed for the entire Southeast Asia, the importance of deepening bilateral relationships and boosting cooperation extends beyond the imperative of managing the geopolitical and geoeconomic consequences. For them, it is about managing and consolidating relationships among neighbors who have experienced ups and downs in the past.

Of course, President Trump’s absurd tariff policy, which created chaos and undermined the global trade system, served as an important strategic context for the visit. There was a clear message that leaders in three countries conveyed to President Xi. They all expressed rejection of unilateralism and reiterated their commitment to multilateralism. The same sentiments might have been expressed in most, if not all, Southeast Asian countries.

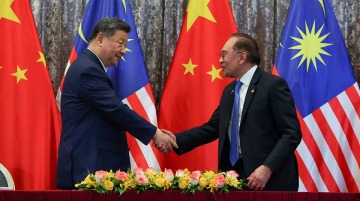

To his counterparts, President Xi also expressed the same rejection and commitment. It becomes clear that the visit underscores Beijing’s intention to position itself as a leader in free trade and globalization. By signing hundreds of cooperation documents, China demonstrates that economic cooperation between states is supposed to be a “win-win” undertaking. Throughout the visit, President Xi consistently sought to project China’s credentials as a trustworthy and reliable partner.

While President Xi’s visit first and foremost provided an opportunity to consolidate China’s bilateral ties with each of the Southeast Asian countries, it also points to the fact that the region is clearly at the crossfire between the U.S. and China.

ASEAN needs to consider how to build a regional security architecture, which, under current circumstances, is shielded from the complexity and problems of great powers’ tension.

Once again, the region is facing a somewhat familiar strategic conundrum stemming from the intensifying rivalry between the two great powers. Both great powers put the region in a difficult position. President Trump, for example, quickly suggested that President Xi’s visit could be seen as an attempt “to screw” the US. China has also warned countries that any party negotiating trade deals with the U.S. will face countermeasures if it harms its interests. The expectation of Southeast Asian countries that they would not have to choose between Beijing and Washington has become increasingly difficult.

Within the context of Trump’s reckless dismantling of the trade system, it would be difficult for Southeast Asia countries not to appear to be siding with China. For purely economic reasons, the interests of Southeast Asian countries are closely aligned with those of China.

No regional states, not even the closest American allies, would see Trump’s policy as something beneficial to them. For non-American allies in Southeast Asia, therefore, the key challenge is how to deal with the U.S. and Trump’s arbitrary tariff policy without compromising their non-aligned stance. Working with China to promote free and fair trade in the region, preserve open regionalism, foster connectivity, deepen regional community-building, and consolidate bilateral economic cooperation provides the best pathway for the region’s prosperity.

In realizing those regional economic interests, Southeast Asian countries, under the umbrella of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), could and should utilize institutional platforms such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The RCEP has the potential to bring together ten ASEAN countries and four dialogue partners— China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand —into closer economic integration. As the global trading system, including the World Trade Organization (WTO), is in a state of dysfunction, it is imperative for regional countries to preserve regional economic cooperation. After all, Indo-Pacific states are all multilateralists.

Yet, the economy is not the only strategic consideration for Southeast Asia.

For once, avoiding strategic dependence on any power and maintaining strategic autonomy will always be twin strategic interests for the region. These strategic interests are at the heart of the institutional and collective objectives of ASEAN. The strategic orientation of regional countries might not always converge. Indeed, in the region, divergent strategic views on security matters seem to be the norm, not the exception. Within ASEAN, for example, some members are treaty allies of the U.S., some are non-aligned, and some are close to China. These differences make it hard for ASEAN to have a unified position in responding to U.S.-China competition beyond the mantra of “hoping not to choose sides” and “hoping to maintain strategic autonomy”. ASEAN urgently needs to build its strategic autonomy so the region will not become a proxy to any great power

ASEAN needs to consider how to build a regional security architecture, which, under current circumstances, is shielded from the complexity and problems of great powers’ tension, especially between the U.S. and Russia. One idea to consider is either to incorporate security cooperation into the RCEP or establish a parallel platform for RCEP member states to cooperate on security and strategic issues. A Regional Comprehensive Security and Economic Partnership (RCSEP) should be contemplated.

ASEAN might be reluctant to entertain the imperative of “going geopolitical.” But, if it wants to find ways on “how not to choose,” then “doing geopolitics” is a sensible choice. And, in keeping true to the ASEAN Way, the “geopolitics way” that ASEAN could travel will continue to combine elements of normative, pragmatic, and realist approaches to security management.

ASEAN, after all, has proven itself to be a masterful manager of regional order in handling key critical strategic changes in the region, from the withdrawal of the US after the Vietnam War to the end of the Cold War. It could do so again now, as the world once again plunges into strategic uncertainty.

Rizal Sukma is a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies CSIS in Jakarta and currently serves on the Board of Advisers at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, or International IDEA, for the 2024–2027 term.