By Kristina Fong Siew Leng

The first 100 days of the Trump 2.0 presidency has been a rocky ride. On the trade front, countries continue to navigate trade negotiations with the U.S. in the current 90-day pause granted on the imposition of the reciprocal tariffs. However, the lack of momentum has projected an image of an administration with no clear strategy. What has added to the complexity of these so-called trade negotiations has also been the inclusion of security issues in talks, raising the stakes for Japan, South Korea and the Philippines.

That said, a persistent U.S. concern is the occurrence of countries acting as conduits for the flow of Chinese goods to dodge tariffs as well as facilitating dumping activities concurrently. The recent U.S. announcement of proposed new anti-dumping duties on solar panels imported from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam underscores the dilemma.

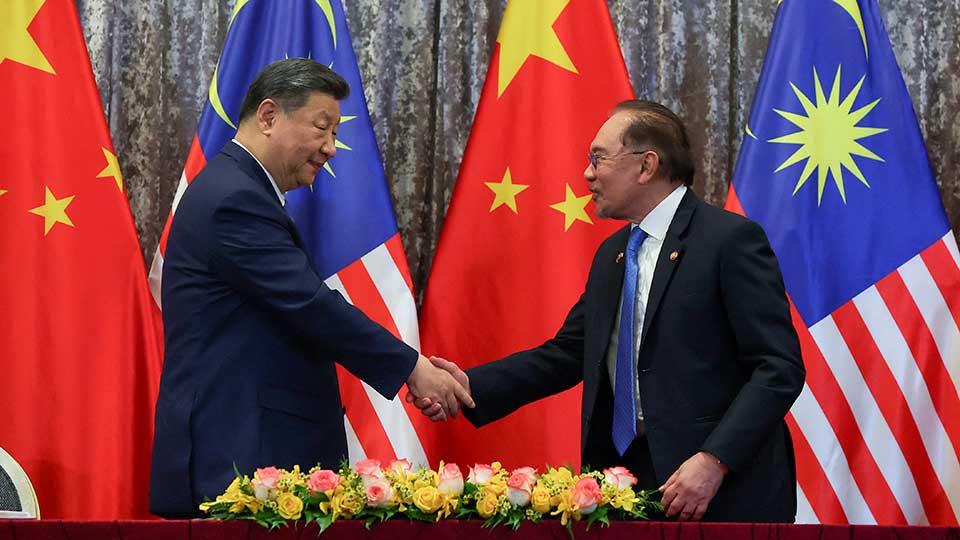

As the war of words continues between the U.S. and China, China has pursued a charm offensive. In April, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia. Among other things, the visits resulted in the signing of a significant number of MOUs. Despite the perceived openness for deepening strategic relationships, China has also not shied away from issuing caution to its trade partners.

Most recently, President Xi warned countries against striking deals with the U.S. that would result in more restricted trade with China. Along with the Trump administration’s steps to crack down on countries perceived to be aiding China in circumventing trade restrictions and the like, there is an underlying message to refrain from strategic relationships that will harm respective parties’ interests. Many regional countries walked this precarious tightrope in the past by maintaining neutrality and staying open to business opportunities from both sides. But the current state of play may further narrow down the range of options available. Both China and the U.S. want to benefit from the region, whilst also limiting the benefits to the other major power.

Given this scenario, what options do ASEAN and its members have? As mentioned, the U.S. remains concerned about the use of export re-direction strategies to circumvent tariffs imposed on China. For one, China has sought out Southeast Asian countries as locations to rebadge exports from China en route to the U.S. Southeast Asian countries have been vocal about this, knowing that allowing this to slip through the cracks makes them prime targets on the U.S.’ radar. In April, Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade issued an official directive to impose stricter management of imported materials for exports.

Most recently, Malaysia has also tightened procedures for the issuance of Non-Preferential Certificates of Origin (NPCOs). The NPCOs confirm the country of origin of exports but do not grant any preferential treatment such as lower tariffs. In effect, they seek to prevent the ‘origin washing’ of products re-routed through the country. The wider crackdown on re-labelling and transhipment activities could encourage China to physically set up manufacturing operations onshore in Southeast Asia or increase the value-added output from existing facilities there.

Southeast Asia has taken a bilateral and regional approach to dealing with the U.S. regarding the reciprocal tariffs. Having this two-pronged approach in tandem may actually be complementary and work to its advantage.

However, a perceived over-supply of these products imported into the U.S. market from these expanded Chinese operations in Southeast Asia could also stir up another issue, much like the latest round of duties levied on solar cells and panels. Thus, a deal struck with the U.S. by Southeast Asian countries in this position may have certain conditions placed on the volume of imports into the U.S., from certain manufacturing sectors. This may be the case unless the over-capacity concerns are dealt with directly between the U.S. and China in their bilateral negotiations. At the end of the day, it may require a bit of give and take by the two major powers.

Southeast Asia has taken a bilateral and regional approach to dealing with the U.S. regarding the reciprocal tariffs. Having this two-pronged approach in tandem may actually be complementary and work to its advantage. The bilateral approach could be used to iron out specific issues, including trade balances and non-tariff barriers which may be in place for reasons unique to each country. These could include specific initiatives to uphold sanitary standards and safeguard food security amongst others. As such, this approach would make it a more efficient and targeted process.

Some ASEAN member states (AMS) do not have strong leverage on account of the perceived unfavourable trade standing with the U.S. or may export products that are more easily substitutable such as garments and footwear from Cambodia or Laos. Countries in this position would benefit from approaching the U.S. through the bloc, using its size and economic heft to improve their bargaining positions. Countries such as Malaysia, which stands as a major supplier of electronics to the U.S., may have some added leverage due to the technical sophistication of these imports. Semiconductors from Malaysia account for 20 per cent of overall U.S. semiconductor imports, and it is harder to find substitutes for them or to reshore production to the U.S. so readily.

At the minimum, ASEAN brings a formidable united front emphasising non-retaliation as well as the continued openness to work with the US to strengthening existing frameworks such as the ASEAN-U.S. Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA). Even then, the appetite of the Trump administration to build upon this established mechanism remains to be seen.

If anything, the current episode has shown us that the situation remains a dynamic one which has created an increasingly uncertain global economic outlook. These developments have caused the U.S. to suffer a knock in its trust standing. That said, most respondents in the State of Southeast Asia Survey also cite a general concern over China’s growing economic influence in the region, making it more difficult to ascertain which major power would be the more reliable strategic partner. No one wins in a trade war and Southeast Asia should strive to minimize losses.

Kristina Fong Siew Leng is Lead Researcher for Economic Affairs at the ASEAN Studies Centre, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

This article was originally published on Fulcrum and republished with the permission of ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute.