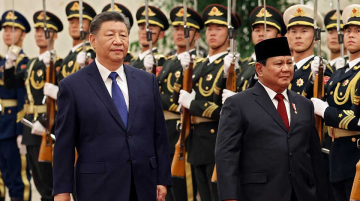

This week, Indonesia and China celebrated 75 years of diplomatic ties with a landmark 2+2 meeting in Beijing — the first of its kind between the two countries. Lavish praise, photo ops, and a new Comprehensive Strategic Dialogue underscored the event’s significance. The tone was optimistic, with promises of increased cooperation on defense, maritime security, and multilateralism.

However, what was conspicuously absent from the public details of the meeting were candid discussions on several critical issues that threaten the relationship between the two countries. These tensions, if left unaddressed, could undermine the long-term sustainability of the partnership.

The most pressing issue that seems to have gone unmentioned was the South China Sea. This maritime dispute continues to be a flashpoint between Indonesia and China. Beijing’s aggressive stance in the region, particularly its claims over vast stretches of the South China Sea, directly threatens Indonesia’s maritime rights. The Chinese Coast Guard routinely enters Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) near the Natuna Islands, often asserting China’s expansive claims despite Indonesia’s protests. Jakarta has repeatedly raised the issue through diplomatic channels and military deployments, yet the 2+2 dialogue offered only vague promises of cooperation on regional maritime security.

The call for “regional maritime security” and improved coordination between Indonesia’s Bakamla and China’s Coast Guard is a positive step but ultimately insufficient. These assurances ring hollow as long as Chinese ships continue to encroach on Indonesia’s EEZ without clear de-escalation or adherence to international law. By not publicly addressing these tensions, both sides risk signaling that Indonesia is willing to tolerate repeated infringements for the sake of economic benefits.

Another critical issue that was not substantively addressed in the meeting is the growing concern over cyberattacks traced to Chinese actors. In recent years, Indonesia has become increasingly vulnerable to cyberattacks, many of which appear to be linked to Chinese state-sponsored or state-affiliated groups. These attacks have targeted government institutions, universities, and even the military, posing a serious threat to Indonesia’s national security and governance. While Jakarta has refrained from openly attributing these attacks to China, the pattern is undeniable.

The absence of critical issues in the public discourse of the 2+2 meeting suggests that both sides may have chosen to prioritize smoothing over tensions at the expense of real progress.

The 2+2 dialogue seemed to offer no meaningful discussion on cybersecurity, even though the issue has become a pressing concern in bilateral relations. Instead, both sides reiterated their commitment to combating transnational crime and cyber threats, but there was no acknowledgment of the role certain actors from China play in exacerbating the problem. The lack of transparency in Chinese cyber activities undermines trust and raises questions about the true extent of cooperation in this area. Without a frank conversation on this issue, any cooperation risks remaining superficial.

Equally troubling is the rising tide of transnational crime involving Chinese nationals operating in Indonesia. In recent years, Indonesian authorities have faced an alarming surge in illegal activities linked to Chinese nationals, ranging from online fraud syndicates to human trafficking networks. Chinese-run businesses and criminal groups have been implicated in a variety of illicit activities, including immigration violations and exploitation of labor. These crimes strain Indonesia’s law enforcement capacity, stoke public resentment, and threaten to erode the trust that underpins the bilateral relationship.

Despite these concerns, the 2+2 dialogue made only a passing reference to cooperation on transnational crime, without addressing the underlying issue of Chinese nationals’ involvement in such activities. The lack of a transparent and accountable approach to addressing these crimes suggests a reluctance to fully confront the problem.

In fairness, the symbolism of the 2+2 dialogue and the establishment of the Comprehensive Strategic Dialogue are important steps in recognizing Indonesia as a key partner in China’s regional strategy. However, strategic partnerships are not built on platitudes alone. They require a willingness to address areas of friction, even when those discussions are uncomfortable.

The absence of these critical issues in the public discourse of the 2+2 meeting suggests that both sides may have chosen to prioritize smoothing over tensions at the expense of real progress.

It’s possible that these issues were raised behind closed doors. But without transparency or a commitment to mutual accountability, it is difficult to gauge whether the meeting resulted in meaningful progress on the South China Sea, cybersecurity, and transnational crime. These are not peripheral issues; they are central to the future of Indonesia’s relationship with China. By not publicly addressing these matters, the 2+2 dialogue risks becoming a diplomatic performance rather than a genuine step toward deeper cooperation.

A particularly troubling aspect of the meeting was Sugiono’s reaffirmation of Indonesia’s support for the One China policy. He went further, labeling Taiwan, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong as China’s “internal affairs.” This rhetorical move, while aligning with Beijing’s stance, underscores an imbalance in the relationship. By prioritizing China’s sensitivities over Indonesia’s own concerns, Jakarta risks diminishing its sovereignty and diplomatic autonomy in favor of maintaining economic and strategic ties with Beijing.

As Indonesia prepares to host the next round of 2+2 talks in 2026, it must use this opportunity to bring these issues to the forefront of the discussion. Addressing the South China Sea dispute, cyber threats, and transnational crimes should be non-negotiable priorities. If Jakarta continues to defer these issues, it risks undermining the trust and mutual respect that the 2+2 format seeks to cultivate.

This article was co-authored by Yeta Purnama, a researcher at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), and Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at CELIOS.