In July, China quietly launched the 1.2 trillion-yuan Metog hydropower project, the largest infrastructure project in human history.

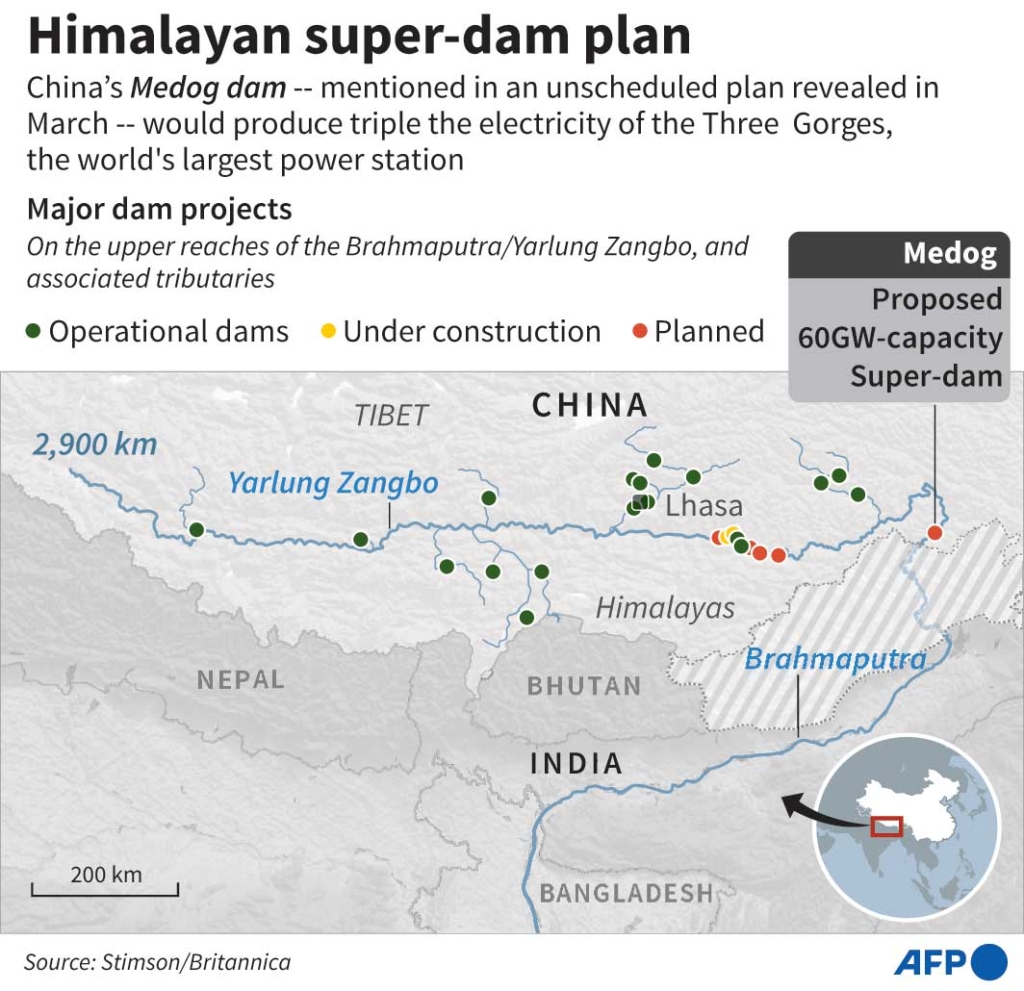

The planned Metog hydropower station sits on the “Great Bend” of the Yarlung Tsangpo, where the river drops 2,000 meters within a 50-kilometer stretch. It is considered one of the world’s richest sites in water and energy resources. The dam’s proposed capacity is 60 gigawatts, roughly three Three Gorges Dams.

But unlike the fierce public debate that once surrounded Three Gorges, this mega-project has drawn almost no discussion inside China. Searches mostly return identical official write-ups and investor commentaries. Outside China, however, its proximity to the disputed China–India border and its location on a transboundary river have fueled alarm in India and Bangladesh.

Recently, the independent Chinese-language outlet Initium Media published a long feature based on interviews with Chinese ecologists and environmental groups. It details the project’s ecological risks, its downstream water-security implications, why its rollout has faced virtually no domestic resistance, how civil-society voices were drowned out by promises of economic returns, and how the project is being framed as critical “AI-era computing power storage.”

An Ecological Fragile Site

The article explains the area’s ecological and geological complexity. The 2,900-kilometer Yarlung Tsangpo flows across southern Tibet, enters India as the Siang River, joins the Brahmaputra, and eventually merges with the Ganges in Bangladesh before reaching the Bay of Bengal. Near the disputed border with India’s Arunachal Pradesh, it forms the world’s deepest canyon, dropping more than 2,000 meters between Gyala Peri and Namcha Barwa peaks. The region sits atop the Indian–Eurasian plate boundary and has seen major earthquakes, including an 8.6-magnitude quake in 1950.

Researchers call this gorge a “treasury of biodiversity”: it contains an estimated 70% of China’s species, including tigers, leopards, clouded leopards, Himalayan black bears, musk deer, civets, and many endemic and isolated species shaped by the deep canyon’s geography.

The project has been on China’s agenda since 2021, when it was written into the 14th Five-Year Plan. That same year, as China hosted the COP15 biodiversity summit, ecologists such as Lü Zhi and Wang Fang warned in Nature that the project threatened the canyon’s fragile ecology and urged the creation of a national park to protect it.

Silence at Home, Secrecy in Operation

Since construction was announced, domestic discussion has centered on investment returns and national-level energy strategy. State media have called it a “strategic move,” arguing it will support China’s future electricity and computing-power needs.

But project details are highly classified: the inundation area, resettlement plans, and environmental impact remain unknown. “It’s three times the size of Three Gorges, in a far more fragile and politically sensitive region, yet it proceeded without a National People’s Congress vote,” wrote Zhang Hong, an international studies professor.

Zhang told Initium Media that she first noticed the project when Indian students asked her about it, only to find almost no Chinese-language discussion. The sudden July construction announcement, she said, reflected political intent to avoid early scrutiny.

Unlike in India, where Indigenous communities, activists, and environmental lawyers continue to challenge dam construction, public participation in China has been sidelined, and key procedures such as environmental impact disclosures and public consultation have effectively disappeared.

Ecologist Wang Xing (pseudonym) said many researchers are worried but cautious because the project touches on national strategy and territorial issues. He described the government’s approach as “thunderous”, moving ahead while bypassing normal procedures such as public environmental review. China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment has denied access to the EIA, calling it classified. Lawyers who tried to obtain the report said they were met with unusually fast rejections and online harassment accusing them of “helping India.”

Everything suggests the project is treated as a national strategic priority. Its leadership team includes figures who oversaw the Three Gorges and major state energy groups. To ease Indian fears of “weaponized water,” Chinese diplomats have recently courted Indian media.

Technically, experts say the project’s ability to manipulate downstream flows is limited because it is a run-of-river dam, not a storage reservoir like Three Gorges.

Serve What Goal?

China already has the world’s largest hydropower capacity, more than Brazil and Canada combined, and many stations suffer from underutilization. Even Three Gorges wastes the equivalent of two-thirds of its annual generation capacity due to “water abandonment.” Yet Beijing is still investing heavily in the Yarlung Tsangpo.

Supporters frame the project as essential for the next stage of development: power-hungry industries such as AI computing, EVs, and energy storage. Under China’s carbon-peaking (2030) and carbon-neutral (2060) goals, hydropower is seen as a reliable low-carbon energy source that can support grid stability and reduce coal reliance. Since 2023, Xi Jinping has promoted “new quality productive forces,” focusing on tech-driven sectors that require steady electricity.

Zhang believes this framing likely serves as political mobilization. Whether the argument is technically sound, she said, it offers a persuasive narrative to policymakers under pressure to promote new strategic industries.

A Geopolitical Flashpoint

In India, debate is far more heated. China’s dam plans have long stirred fears over water security. India is now proposing its own giant dam and reservoir on the Siang as a countermeasure, with 11,000 MW capacity and a dam height of over 500 meters, intended to “buffer” Chinese releases. But the project threatens to displace around 150,000 indigenous Adi people and submerge 27 villages, sparking strong protests.

Adi activists warn that the dam would destroy ancestral lands, farmland, cultural sites, medicinal plant habitats, and unique regional species. Sitting in an earthquake-prone zone, it could also increase seismic risks.

Why Is This Important? The article highlights how space for public oversight in China has sharply narrowed. Civil society once capable of scrutinizing large hydropower projects can no longer meaningfully intervene, even as projects grow bigger, riskier, and more politically sensitive.

Unlike in India, where Indigenous communities, activists, and environmental lawyers continue to challenge dam construction, public participation in China has been sidelined, and key procedures such as environmental impact disclosures and public consultation have effectively disappeared. The Metog project shows how massive infrastructure can now bypass once-standard checks entirely, taking shape under strict information controls and minimal transparency.