When the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Kadin) opened its doors to Xinjiang’s state-linked conglomerates this month, the event was billed as a milestone in deepening trade ties.

Executives from Jakarta and Urumqi spoke glowingly of “mutual respect” and “resilient supply chains.” The Chinese ambassador in Jakarta, Wang Lutong, highlighted that bilateral trade had surged to nearly $63 billion in the first five months of 2025. And, as if to underscore the cultural affinity between the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation and China’s far-western region, officials spoke of shared Islamic traditions and the promise of halal food cooperation.

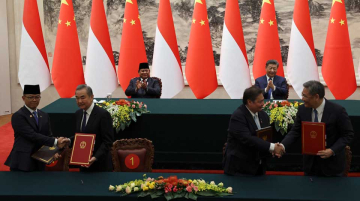

Yet behind the polished speeches and handshakes lies a troubling paradox. Indonesia is strengthening ties with a region synonymous not with mutual respect but with repression: Xinjiang, where the Chinese government stands accused of mass surveillance, arbitrary detention, and forced assimilation of Uyghur Muslims.

The latest flurry of cooperation agreements—including a memorandum between Universitas Al Azhar Indonesia and Tarim University in Xinjiang—are not merely educational exchanges or investment deals. They are part of Beijing’s sophisticated campaign to rebrand Xinjiang internationally, particularly to Muslim-majority nations wary of Western narratives of human rights abuses.

By showcasing “cultural closeness” and agricultural potential, China hopes to shift the conversation away from internment camps and religious restrictions.

Indonesia’s Dilemma: Growth vs. Responsibility

Indonesia, however, faces a dilemma. On the one hand, it heavily depends on Chinese capital, infrastructure funding, and markets. China has been pivotal in financing Indonesia’s ambitious industrialization push and expanding collaboration across critical sectors—from energy and agriculture to logistics, technology, and education.

These partnerships have helped Jakarta accelerate its development agenda and reinforced the perception that deeper engagement with Beijing is essential for sustaining growth. On the other hand, Indonesia’s citizens—many of whom identify strongly with the global Muslim community—are not blind to the reports emerging from Xinjiang.

Indonesian civil society organizations, Islamic groups, and students have periodically demanded that Jakarta take a clearer stance on China’s treatment of Uyghurs.

Until now, Jakarta has chosen caution over confrontation. Successive governments have steered clear of publicly challenging Beijing, opting instead for muted diplomacy and a steady focus on safeguarding economic ties.

Under President Prabowo Subianto, whose signature vision is Indonesia Emas 2045—a national blueprint that aspires to make Indonesia one of the world’s five largest economies by its centenary of independence—the calculus tilts even more toward pragmatism.

Achieving this goal requires massive investment in infrastructure, energy, technology, and human capital, much of which Indonesia hopes to secure through external partnerships. In that context, every potential collaborator is measured less by political baggage than by their ability to help deliver growth.

Xinjiang—framed by Beijing not only as an economic partner but also as a region with purported cultural and religious ties—becomes a particularly convenient channel for China to deepen its influence in Indonesia under the banner of mutual progress.

Risks of Reputational Damage

It is worth remembering who exactly Indonesia is partnering with. The centerpiece of this new cooperation is the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), a sprawling state-run entity with deep ties to the Communist Party, the military, and the regional security apparatus.

Far from being a neutral business group, the XPCC has been sanctioned by the United States and others for its alleged role in human rights abuses and demographic engineering in Xinjiang. For Indonesia to sign trade, investment, and energy deals with such an institution risks not only complicity but reputational damage on the global stage.

China’s narrative emphasizes resilience, inclusivity, and prosperity. Yet, for many Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim minorities, life in Xinjiang has meant exactly the opposite.

Reports from human rights groups describe mosques demolished or repurposed, children separated from their families, and communities subjected to mass indoctrination.

While Beijing insists its policies are about countering extremism and promoting development, the scale and methods of its programs have drawn condemnation from Western governments and watchdogs alike.

Indonesia cannot claim ignorance. Its policymakers and business leaders know that cultural exchange programs and academic partnerships are not taking place in a vacuum; they are unfolding in a region where independent access and scrutiny remain tightly controlled. Universities signing memorandums of understanding with their Xinjiang counterparts must grapple with the uncomfortable reality that their collaborations may serve as instruments of soft power for a government seeking to normalize repression.

For a country that has long prided itself on being a moral voice in the Muslim world, Indonesia risks sending a dangerous signal. By embracing Xinjiang uncritically, it risks appearing to endorse Beijing’s narrative while sidelining the concerns of fellow Muslims whose faith and freedoms are under siege.

Indonesia is, of course, entitled to pursue economic opportunities and cultivate partnerships. But it should do so with clear-eyed realism about the political context. Engagement does not have to mean silence. Jakarta could—and should—insist that economic cooperation be accompanied by genuine transparency in Xinjiang, access for independent observers, and safeguards that ensure partnerships are not tainted by repression.

As Indonesia accelerates its march toward 2045, it must ask itself what kind of global leader it wants to be. Economic prosperity at the expense of moral responsibility may seem expedient today. But in the long run, history rarely looks kindly on those who confuse silence with neutrality.

This article was co-authored by Yeta Purnama, a researcher at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), and Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at CELIOS.