In this edition of Myth and Misperception, I want to take a deep dive into one of the most contentious debates on Vietnam’s foreign policy: what role does ideology play in the country’s foreign policy? As a communist party-state, Vietnam officially adheres to Marxism-Leninism in every aspect of governance. Many policy writings often follow a similar script: a writer cites what Marxism-Leninism has to say about a specific topic, explains how President Ho Chi Minh adapted the theory to the Vietnamese context, and finally advises how the government should model their policy after the theoretical suggestions. Foreign policy is not an exception.

What is the Ideology Explanation?

The fact that Marxism-Leninism is the state’s official ideology gives rise to a conviction that Vietnam’s foreign policy is ideology driven and that strategic material gains play limited roles in dictating Vietnam’s behaviors.

The ideology argument explains Vietnam’s foreign policy, especially its decision to conflict or cooperate with other countries, in two ways. Vietnam goes to war because it must (1) defend its communist ideology from a hostile ideology or (2) spread the communist ideology out of its commitment to proletarian internationalism and to attack other hostile ideologies. In the same vein, Vietnam will cooperate with a foreign partner if it shares the same ideology or if the partner commits to not hurting Vietnam’s ideology. In both cases of conflict and cooperation, ideology helps distinguish between friends and foes.

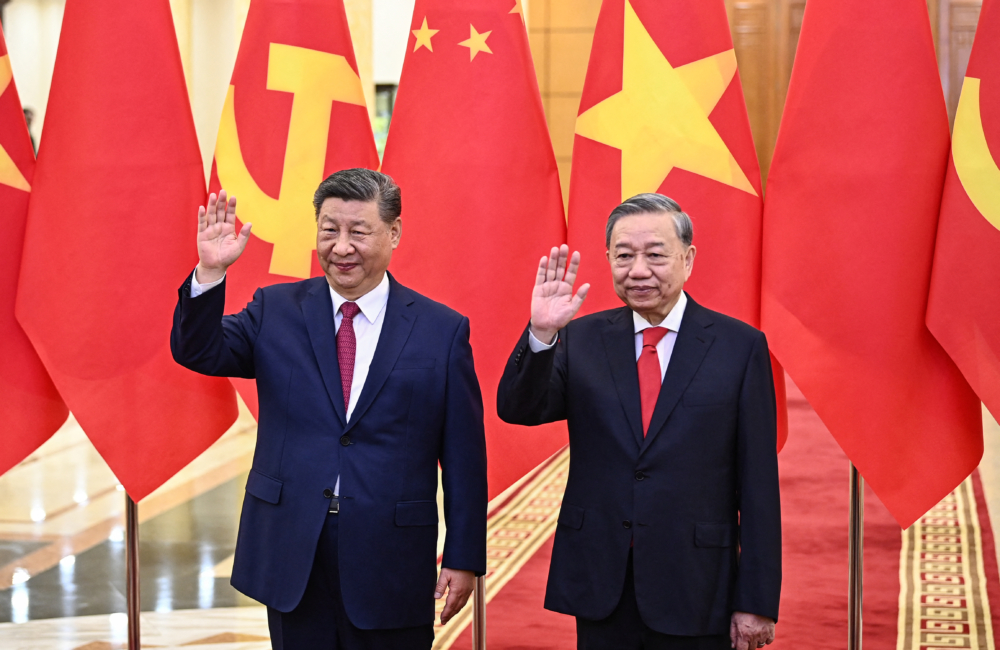

In some aspect, this connects to my previous analysis of another myth in Vietnam’s foreign policy, that there is a pro-U.S. and a pro-China faction. The existence of a pro-China faction stems from so-called “ideological conservatives” perceiving China as an ideological ally.

That faction opposes closer cooperation with the United States because of its skepticism of the U.S. intention toward the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV).

Why Do People Believe It?

I think ideology is a valid factor to consider because there is empirical support. Vietnam’s First and Second Indochina Wars could be explained from an ideological perspective – that because Marxism-Leninism opposed colonialism and capitalism, Hanoi fought against France and the United States. Proletarian internationalism explained why Hanoi helped communist movements in Laos and Cambodia during the two wars.

The ideology argument has a more difficult time explaining the Third Indochina War, as Vietnam was fighting against its former comrades Khmer Rouge and China. However, the conflict could be justified in terms of a disagreement over the understanding of Marxism-Leninism (like the ideological explanation for the Sino-Soviet Split). Hanoi’s backing of the Heng Samrin government in Cambodia after overthrowing the Khmer Rouge in January 1979 was an act of proletarian internationalism and its opposition to how the Khmer Rouge was implementing Marxism-Leninism in Cambodia, remarkably by imprisoning and executing a great number of the population.

What Does the Data Show?

To be clear, the ideology factor itself is not a myth. It is how observers spin it for their own political agenda, without any empirical evidence, that is problematic. For example, it is not hard to find arguments, especially from anti-communist outlets, that Hanoi “ceded” territories to Beijing in the 1999 and 2000 land and Gulf of Tonkin boundary treaties because of shared communist ideology (it did not).

Or that Vietnam does not oppose China’s aggressive behaviors in the South China Sea because the CPV is ideologically subservient to the Chinese Communist Party (also not true). Claims about the existence of a pro-China faction are also scientifically unsound because of a lack of evidence about the key figures and what impact they exert on Vietnam’s foreign policy.

At the same time, we must be aware of the scientific limitations of ideology in explaining Vietnam’s foreign policy because it ignores the material constraint that Vietnam has to navigate. As a communist party-state, Vietnam must ensure that both the party and the state survive. The party cannot compromise the state’s material resources in pursuit of its ideology because without a state, the party is just a political organization and it will lose both its domestic and international sovereignties.

A strong state in material terms, i.e. military, economy, territory, will be useful for the party to further its agenda. From this strategic lens, Vietnam’s decision to fight France, the United States, China, and the Khmer Rouge is attributed to its determination to protect the state, which includes territorial integrity and the monopoly to the legal use of force within its own territory. Hanoi has been determined to protect its maritime claims despite the shared ideology with China. Access to the sea is important for the party-state’s socio-economic development and by extension the party’s survival via performance-based legitimacy.

What Do the Findings Mean?

Ideology is a valid factor, but it alone may not tell you the full story. I think that both ideology and strategic calculations play a leading role in Vietnam’s foreign policy. The important point is to know how either of them matters and in what context. Since the Cold War ended, Vietnam has de-ideologized its foreign policy by normalizing and upgrading ties with countries of different political systems on the basis of mutual respect and mutual benefit.

The “ideologically hostile” United States is the largest buyer of Vietnamese exports, but that doesn’t mean Vietnam completely trusts the U.S. assurance that it will respect the CPV. Observers should be willing to do a little more digging beyond the surface because ideology is not always the answer.

Khang Vu is a visiting scholar in the Political Science Department at Boston College