By Koh Sin Yee

Since at least 2019, China has become Malaysia’s top source of international students, overtaking traditional sources such as Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Pakistan. In 2023, a total of 44,043 Chinese students constituted 38.4 per cent of all international students enrolled in Malaysia’s public and private higher education institutions (HEIs). In 2024, Chinese student enrollment in Malaysian HEIs showed a fivefold increase from 2019.

Broadly, there are three contributing factors to this recent increase in Chinese student mobility to Malaysia: (1)

- Shifts in immigration stances in traditional study destination countries.

- Geopolitical tensions and worsening bilateral relations between China and some traditional study destination countries.

- Country-specific conditions in Malaysia and China. Importantly, these factors do not operate in silos; it is their concurrent existence that facilitates the current trend.

First, the shift towards more restrictive immigration stances in the “big four” study destinations (Australia, Canada, the UK and the US) is making them less attractive to Chinese students. This shift is evident in new initiatives such as capping international student numbers, increasing visa costs, imposing stricter student dependent rules, and limiting access to post-study work visas.

This situation is exacerbated by funding cuts in these countries’ higher education sectors, which reduce their attractiveness to international students (e.g., fewer scholarships, less vibrant research and study environment). The rise of Sinophobia in some of these destination countries, especially during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, has also led to safety and security concerns on the part of prospective Chinese students and their families.

Second, the current geopolitical climate, with rising China-US tensions and worsening bilateral relations between China and some traditional study destinations, has contributed to declining Chinese student mobility to these countries. In the US, it has been observed that universities have become extensions of political power. Indeed, Proclamation 10043 (Proclamation on the Suspension of Entry as Nonimmigrants of Certain Students and Researchers from the People’s Republic of China), signed by U.S. President Donald Trump in May 2020, suspended and limited the entry of Chinese students associated with China’s military and high-tech agenda. In 2023, the U.S. rejected a record high of 36 per cent of Chinese student visa applications.

Chinese student enrollment in U.S. HEIs dropped 25 per cent from 372,532 in 2019/20 to 277,398 in 2023/24. US allies such as Australia and Canada have also imposed restrictions on visa applications from Chinese students, especially those intending to undertake studies in “sensitive” fields in advanced science and technology. While Chinese students and researchers were previously viewed as welcome talents, they are now increasingly perceived as potential threats to these countries’ military and intellectual security.

Overall, the above factors have made Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US less attractive, even hostile, environments for Chinese students, especially those planning post-study employment and settlement in these countries.

Malaysia offers an alternative pathway for Chinese students who are seeking a more cost-effective, proximate, comfortable, and secure overseas study experience, bypassing the West.

By contrast, Malaysia is increasingly seen as an appealing study destination for Chinese students owing to a combination of sociocultural and pragmatic reasons, alongside closer Malaysia-China bilateral relations. The presence of Malaysian-Chinese communities (third or fourth generation overseas Chinese) means that Malaysia offers a soft landing for Chinese students who may be living overseas for the first time. Some Chinese students may have family connections in Malaysia, which constitute additional assurance to their parents.

Chinese students can take advantage of a shared language (Mandarin and the use of simplified Chinese characters) and dialects, food, and sociocultural practices. Malaysia thus offers an international yet familiar environment – a comfortable home away from home.

Malaysian HEIs’ favourable positions in global university rankings are also a major draw. Another attractive factor is the relatively more affordable tuition and cost of living in Malaysia. In addition, the geographical proximity and the availability of affordable flights between Malaysia and Chinese students’ home cities enable frequent home visits.

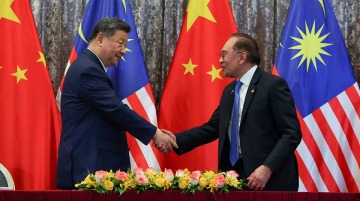

Malaysia may also have acquired greater visibility as a study destination for Chinese students because of the improved political and economic relations between Malaysia and China in recent years. Notably, the establishment of Xiamen University Malaysia (XMUM) in Sepang in 2015, the first international campus of a prestigious Chinese public university, signals a commitment to China-Malaysia bilateral collaborations in education.

Every year, XMUM admits about 500 Chinese students directly through China’s gaokao (National College Entrance Exams). Malaysia’s state-led student recruitment engagements with prospective Chinese students and education agents in China have also contributed to the country’s visibility in the Chinese market.

With rising graduate unemployment in China, more Chinese students are seeking overseas postgraduate degrees to enhance their competitiveness in the domestic and international labour markets. By studying in Malaysia, Chinese students gain access to an affordable, English-medium education with credentials that are recognised in China and elsewhere. Malaysia thus offers an alternative pathway for Chinese students who are seeking a more cost-effective, proximate, comfortable, and secure overseas study experience, bypassing the West.

Malaysia’s current Chinese student mobility trend may be part of a longer-term trend of intra-regional Chinese student mobility (e.g., to Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Thailand) and global student mobility pivoting towards Asia and Southeast Asia. The extension of Malaysia’s post-study Graduate Pass to Chinese nationals (currently until 31 December 2026) will certainly add to the country’s attraction to Chinese students. Given this trend, Malaysia’s HEIs must be prepared for the influx of Chinese students and their study abroad needs (e.g., English language support, social integration, career guidance) by investing in additional manpower, resources, and infrastructure.

Koh Sin Yee is Visiting Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, and Senior Assistant Professor at the Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam.

This article was originally published on Fulcrum and reprinted here with the permission of the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.