By Kevin P. Gallagher

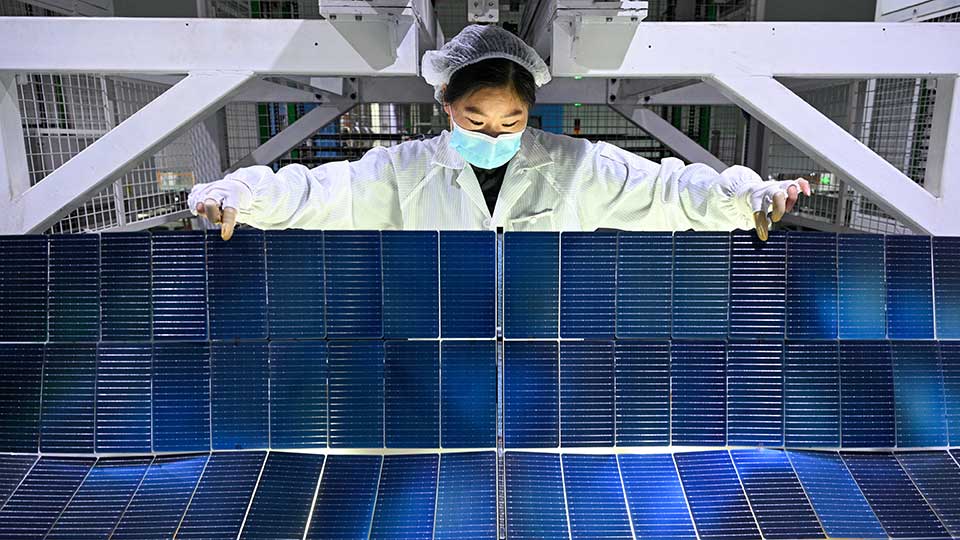

For decades now, China has advanced a big push in both policy innovation and public investment to become the global leader in low carbon technology trade. While deploying these innovations is beginning to transform the Chinese economy, Chinese exports of low carbon technology have significantly reduced carbon dioxide emissions across the world—especially in higher-income countries and countries in the Global South that receive significant amounts of development assistance.

As we know, the United States and Europe are now erecting trade barriers to low carbon technology (among other goods and services) and either eliminating or greatly curtailing foreign assistance. This will likely have a profound impact on global carbon emissions. Moving forward, China will need a new trade and climate strategy for the Global South.

Earlier this year, the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center) created and published a global low carbon technology (LCT) trade database in the journal Science. The paper adapted low carbon classification schemes to global trade data and found that 90 percent of low carbon technology trade is between high-income countries and China—with China (and a handful of EU countries) as the largest producers of these technologies and North America as the largest consumers.

Countries across the Global South account for a very small proportion of LCT trade and struggle to produce or consume such technologies due to increasing levels of external debt service and a lack of policy space under trade and investment treaties.

With this data in hand, the GDP Center collaborated with colleagues from China’s Liaoning University to statistically identify the drivers of China’s LCT and their impacts on global carbon emissions. This research was recently published in the China Economic Review.

We found that a country’s income, trade openness, education, political stability, and the level of development assistance it receives were among the key drivers of Chinese LCT trade. In other words, higher-income and politically stable countries, in addition to developing countries with significant levels of development assistance, tend to receive more Chinese LCT.

In terms of impact, we unequivocally found that LCT trade is associated with reductions in carbon emissions in the countries that engage in LCT trade with China.

These findings are very concerning given that two of the drivers of Chinese LCT trade—trade openness and development assistance—are now on the decline.

In the intermediate run, it will be paramount to reduce barriers to trade and investment and increase development assistance from countries in the Global North, but the near-term political feasibility of such a strategy is highly unlikely. In this light, it is important for China to partner with countries in the Global South to accelerate the green transition through increased low-cost lending and foreign direct investment in LCT.

The Chinese benchmark rate hovers near the concessional rates of the International Development Association (IDA) at around 1.5 percent. For countries with significant debt vulnerabilities, China could refinance its longer-term loans into 30-year panda bonds at much lower interest rates. For those countries and countries not in danger of debt distress, China could also issue new long-run green panda bonds at low rates for green projects.

Furthermore, for countries with manufacturing capabilities in electric vehicles, solar and wind, China should also engage in green foreign direct investment to get closer to markets and enable countries to build their own manufacturing capabilities for the green transition.

Such a strategy will help alleviate debt vulnerability and enable green transitions in the Global South. It would also help China create new markets and solidify South-South Cooperation. Collectively, such partnerships can set an example for a new era of green development cooperation in an increasingly isolationist world.

Kevin P. Gallagher is the Director of the Boston University Global Development Policy Center and a Professor of Global Development Policy at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University. Follow him on X: @KevinPGallagher.