In West Java, a province just east of Jakarta, Indonesia, a sprawling industrial park is rising. Backed by Chinese cement giant Hongshi Holding Group, the $5 billion complex promises to produce the solar panels and batteries that the world desperately needs to combat climate change.

But there’s a paradox at the heart of this green energy dream: the park will be powered by a new 2-gigawatt coal-fired power plant built right on site.

At first glance, this seems like a shocking contradiction. How can a facility that makes solar panels — supposed to help the world cut emissions — be fueled by coal? The truth is, it’s not surprising at all.

Solar panel manufacturing is an electricity-intensive process, and as of 2025, over 60 percent of that electricity globally comes from coal. Countries with abundant coal reserves or cheap coal-based power remain major production hubs. This isn’t unique to China or Indonesia — it’s a global reality rooted in the economics of energy-intensive manufacturing.

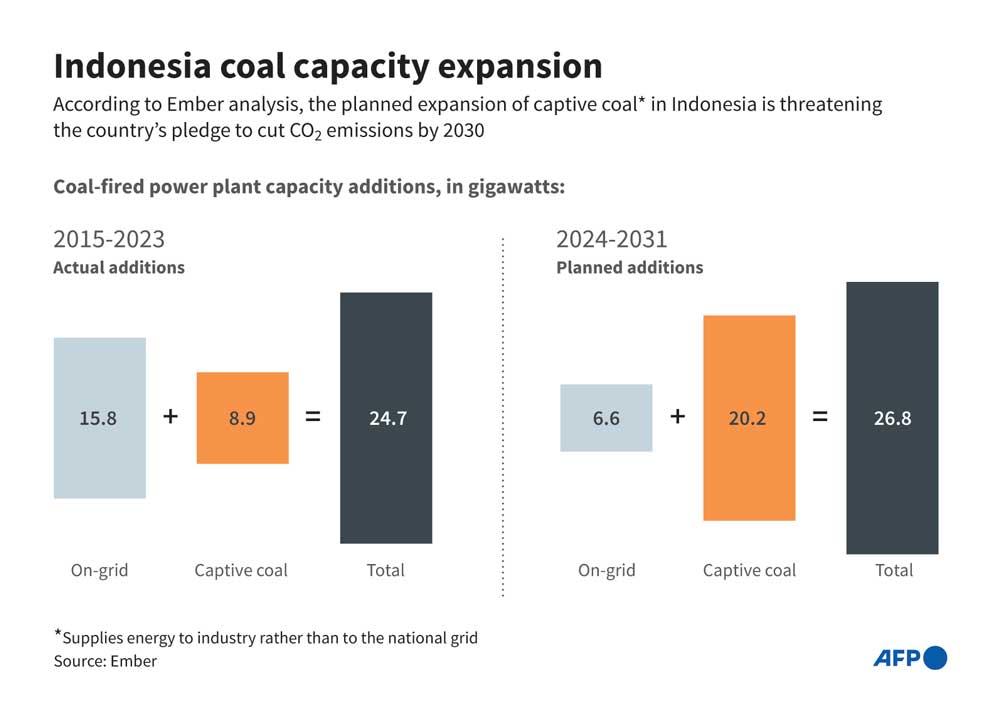

Indonesia’s government has supported the project, with a provincial liaison agency publicly endorsing it. The coal plant will be “captive use,” meaning it won’t feed the national grid but will directly power the industrial park. That designation also allows the project to tap Chinese state-backed loans that would otherwise be banned as part of President Xi Jinping’s 2022 pledge to halt debt financing for overseas coal power plants connected to public grids.

Climate Pledges and Coal Realities

Indonesia has pledged to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2060. Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto has vowed to achieve 100 percent renewable energy within the next decade. Yet Indonesia is simultaneously the largest coal exporter in Southeast Asia, sending an astounding 471 million tons of coal abroad in 2022 alone.

This dual role — championing climate commitments while fueling coal consumption and exports — is not new, but it is a glaring contradiction.

The Hongshi project embodies a pattern well-known in global manufacturing: investors will operate within the policy environments they encounter. If coal power is allowed and affordable, that’s the fuel they will use. The responsibility here lies primarily with Indonesia’s government and regulatory system, which often permits and promotes coal-based industrial development.

This dynamic is not unique to Indonesia or China. Many advanced economies outsource their pollution-heavy manufacturing to countries with looser environmental standards. It’s a global system where countries like Indonesia offer lower costs and lighter regulation, attracting foreign investment. The result is that “clean” products purchased in Europe or North America often rely on carbon-intensive manufacturing in Southeast Asia or elsewhere.

The reality is stark: large parts of the global clean energy transition are being built on a foundation of coal. This is a fact experts have acknowledged for years — it’s not a new revelation. The emissions from a single 2-gigawatt coal plant are enormous, and while they may not appear on Western carbon accounting sheets, they contribute fully to global warming.

Indonesia has enormous renewable energy potential — solar, hydropower, geothermal. Yet the infrastructure to fully harness this potential, especially at the scale needed to power heavy industry, remains underdeveloped. Without robust investment in grid infrastructure, storage, and transmission, coal remains the only reliable source for large-scale, continuous power demands.

Jobs, Growth, and Long-Term Risk

Supporters of the Hongshi project argue it will bring much-needed jobs, infrastructure, and reliable energy. Those are valid considerations. But no credible long-term industrial strategy that aims to meet climate goals includes coal. Locking in coal infrastructure for decades undermines Indonesia’s green ambitions and exposes the country to future economic and environmental risks.

Indonesia is geopolitically significant. It’s the largest economy in Southeast Asia, a member of the G20 and BRICS, and a key player in global climate negotiations. But it is also one of the world’s largest coal producers and exporters, making it a paradoxical actor on the climate stage. While it speaks of climate leadership abroad, it feeds global coal consumption at home and overseas.

This raises complicated questions: Why does Indonesia continue to prioritize coal? Why hasn’t it curtailed its massive coal exports or accelerated a shift to renewables with the urgency its climate commitments suggest?

The answer lies in political economy — coal production and export revenues remain crucial for the country’s economy and influential stakeholders within the government and industry.

The question is not why Indonesia is allowing a coal plant to power solar manufacturing. The question is why anyone expected otherwise, given Indonesia’s energy and economic realities.

The source of electricity matters. Indonesia’s role as a top coal exporter means it’s deeply embedded in fossil fuel infrastructure and markets. Until that changes, even “green” manufacturing projects will remain entwined with fossil fuels.

The Limits of the Energy Transition

This is not a problem unique to Indonesia. Countries like Australia, Canada, and Norway, among others, also struggle with similar contradictions — profiting from fossil fuels while pledging climate action. Yet Indonesia’s scale as a coal supplier in Asia makes it a particularly telling example of the tensions between economic development and climate responsibility.

To truly align with its climate commitments, Indonesia will need to do more than build isolated renewable projects or make pledges. It must overhaul its energy policy, reinvest in renewable infrastructure, and chart a credible pathway away from coal dependency.

Until then, projects like the Hongshi industrial park will remain emblematic of the limits and contradictions of the global energy transition — and Indonesia’s role within it.

This article was co-authored by Bhima Yudhistira Adhinegara, Executive Director of the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), and Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk at CELIOS.