Over the last two decades, China has moved from the periphery to the very center of Africa’s power sector story. It has done so not quietly, but with the kind of scale, speed, and scope that makes it impossible to ignore. And yet, for all the attention it has attracted, a basic question still drives much of the research in this space: just how much is China actually investing?

That question is surprisingly hard to answer with clear accuracy. Chinese policy banks, state-owned enterprises, and private investors rarely publish detailed, systematic, and disaggregated data on their overseas projects. Host governments, often bound by confidentiality clauses, also release few details.

The result is a murky information landscape where firm numbers are scarce, project details are incomplete, and media coverage sometimes circulates figures from abandoned or entirely fictitious projects.

Because of these gaps, an outsized share of academic and policy research has been devoted simply to establishing a baseline: assembling datasets, triangulating multiple sources, and weeding out false or inflated claims.

This is where a tool like the China Global South Project’s China-Africa Energy Tracker becomes invaluable. It moves beyond static tallies to an interactive, living map of projects where Chinese entities are financiers, builders, equipment suppliers, or strategic partners.

By covering not only what is being built and where, but also how it is being financed and at what stage of development, it offers a dynamic, up-to-date picture that policymakers, researchers, and communities can interrogate in real time.

The CGSP produced a new report titled “Powering Africa: China’s Expanding Role in the Continent’s Energy Future” to accompany the tracker. This report is a companion analysis that not only maps the contours of China’s current energy involvement in Africa but also explores what the data tells us about regional trends, financing patterns, and the wider development implications.

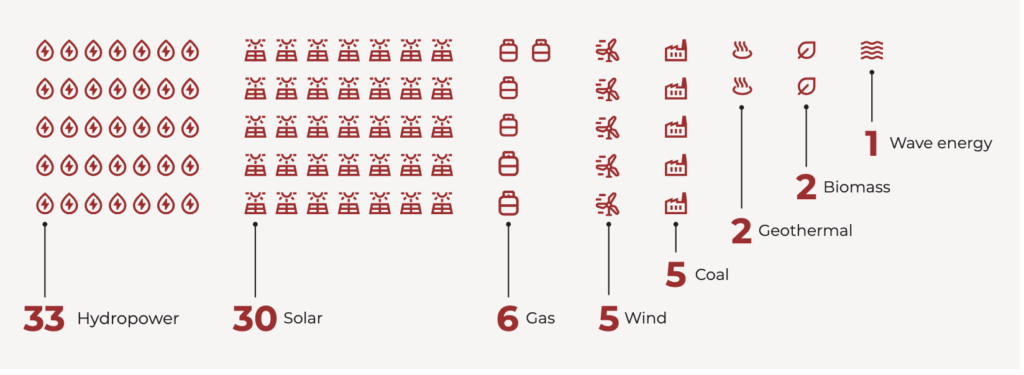

The latest tracker results are a reminder of why such tools matter. Between 2020 and 2024, Chinese companies and financiers have been involved in 84 energy projects across the continent, with a combined capacity of more than 32 gigawatts – enough electricity to light up over 135 million urban African homes, or more than half a billion rural homes, every year.

But the value of the tracker lies not just in these headline figures. It lies in its ability to highlight patterns, identify gaps, and spotlight outliers – the essential starting points for informed discourse and action on Africa’s energy future. So what exactly does the report tell us?

Patterns in the Power Map

The regional breakdown outlined in the report offers a window into Beijing’s priorities – and Africa’s. Southern Africa hosts the largest share, with 35 projects amounting to over 16 gigawatts. Zambia stands out with 11 projects, while Zimbabwe follows closely with nine.

In West Africa, hydropower and gas dominate, with Nigeria’s 6,690 megawatts across six projects reflecting its scale as the continent’s biggest economy. East Africa shows a mix of hydropower and geothermal, while North and Central Africa present smaller but strategically chosen portfolios.

From Dams to Panels: A Technology Tilt

Hydropower remains the flagship of Chinese involvement, accounting for over 13 gigawatts of capacity. Large dams appeal for their long lifespans and ability to provide baseload power, but they also carry heavy energy security, environmental, and social footprints – resettlement, habitat loss, and the ever-present risk of drought, which threatens energy security.

Solar is rising fast, with 30 projects contributing over 3 gigawatts. This reflects not only Africa’s abundant solar radiation but also falling technology costs and quicker construction timelines. The presence of wind, geothermal, and wave energy projects, while smaller in number, signals experimentation and a willingness to match technologies to local conditions.

Finance and Footprints

One of the more striking findings is that Chinese companies built 79 out of the 84 projects tracked. Even where Chinese policy banks were absent, Chinese contractors were often the preferred builders or equipment suppliers. Financing, where traceable, shows CHEXIM’s dominant role, supporting more than 20 projects.

However, for nearly half of the projects, the financing structure remains unclear, a reminder of just how patchy public information can be. This opacity matters. Without clear terms, it is difficult to fully assess debt sustainability, long-term affordability, or the distribution of benefits. It also constrains the ability to learn from successes – or to avoid repeating costly mistakes.

Why Transparency Matters Now

The report’s clearest warning is about information gaps. For 46 out of 84 projects, the financing modality is unknown. Many lack complete data on timelines, cost breakdowns, or contractual terms. This is not simply an academic inconvenience — it directly limits the ability of African governments to plan effectively, negotiate future deals from a position of strength, and ensure that infrastructure serves long-term national interests.

Without better disclosure, the cycle repeats: projects risk underperforming, maintenance gets underfunded, and opportunities to replicate success are lost. Transparency is not just about accountability; it is about building the institutional muscle to manage complex infrastructure in a way that maximises benefits and mitigates risks.

Or, as the Akan proverb from Ghana reminds us: “If you see your neighbor’s beard burning, fetch water by yours.” One is supposed to learn from the experiences and circumstances of others, but without visibility into how projects succeed or fail, host states are forced to fight the same fires again and again, wasting time, resources, and political capital on lessons they could have inherited.

Looking Ahead

As Africa works toward universal electricity access, the stakes could not be higher. Chinese engagement will remain a major force, whether in multi-billion-dollar dams or smaller, decentralized solar farms. But the ultimate value of these investments will depend on more than megawatts delivered. It will hinge on the terms agreed, the knowledge transferred, the environmental footprint left behind, and the resilience of the systems built.

The China-Africa Energy Tracker and the accompanying report are vital steps in that direction. By mapping not just where projects are, but how they are financed, built, and operated, they provides a foundation for evidence-based dialogue and action.