By Jorge Heine

Amazingly, a subject as obscure as whether a Latin American country would sign on to a particular Chinese international cooperation program made headlines around the world these days. “Brazil becomes the second country after India not to join China’s BRI,” crowed The Economic Times, India‘s leading financial daily. Less well informed, The New Civil Engineer stated, “Brazil third country to pull out of China’s multi-billion-dollar vision to construct ‘new Silk Road’ “(false: only one country has “pulled out” of the BRI, Italy, under the far-right government of Giorgia Meloni).

After Brazil’s alleged veto of Venezuela to join the BRICS group at their 16th summit in Kazan on 22-24 October, some speculated that this would indicate a major right-ward shift in Brazilian foreign policy.

Is this true? Has the Brazilian leopard changed its spots?

Admittedly, Brazil’s decision raised eyebrows and merits an explanation. A total of 22 Latin American and Caribbean countries have signed BRI MOUs with China (after President Gustavo Petro’s recent visit to China, Colombia may become the 23rd). This is China’s flagship foreign policy project, one that has spent a cool one trillion dollars on various infrastructure and connectivity projects around the world since 2013, mostly in the Global South. Brazil is China’s leading trading partner in Latin America, with bilateral trade reaching $181 billion in 2023 and Brazil running a significant surplus.

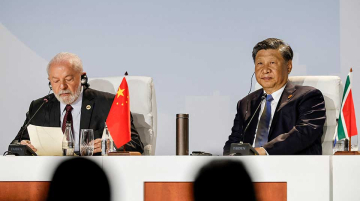

About half of Chinese investment in the region –around $73 billion—has flocked to Brazil. President Xi will visit Brazil for the G20 summit to be held in Rio de Janeiro on 19-20 November. Being able to announce Brazil’s joining the BRI would have been the icing on the cake for such a visit, much as the inauguration of the Chinese-built deep-water port of Chancay will be for Xi’s visit to Peru for the APEC summit in Lima on 15-16 November.

Yes, Brazil had been one of the last holdouts in the region not signing on to the BRI (Mexico is another), but there had been much speculation in the last few weeks that it would do so now. Why spoil things at the last moment and, by not signing, provide yet another talking point to China hawks everywhere? Are we really witnessing a major move away from China in Brasilia?

Or is this an unexpected and highly unusual faux pas of Itamaraty’s fabled diplomacy? How much of this decision not to sign the BRI was spurred by the warning issued by U.S. Trade Representative Katerine Tai, who, speaking at the Bloomberg New Economy meeting in Sao Paulo on 23 October, warned Brazil to consider the risks of joining China’s BRI?

Yet, I would argue that the media is making a mountain out of a molehill. Whereas Latin American countries started signing BRI MOUs in 2018 (Panama was the first to do so), for a variety of reasons, the larger countries in the region decided that BRI was not worth the candle. Their reading was that their economic heft was such that China would do business with them anyway.

For a long time, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico held out. Argentina’s foreign debt travails made it finally give in, and it signed on in 2022. Colombia has long been a regional laggard in its links with China, and President Petro concluded that getting on board the BRI may be a good way to make up for lost time. Mexico, for obvious reasons, is not able to sign on, but strictly speaking, there are no compelling reasons for Brazil to sign on to the BRI either. Given its size and rising power status, Brazil will always be China’s preferred partner in the region, no matter what it does.

And here let us note the traditional prudence of Brazilian foreign policy. In his first two terms (2003-2011), President Lula was, in many ways, the ultimate champion of the Global South. Brazil was a founding member of the India-Brazil-South Africa Initiative (IBSA), an entity that brought together three leading democracies from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. It was also a founding member of the BRICS group and a founding member of the Beijing-based Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank (AIIB).

Yet, surprisingly, in all these years, Brazil never joined the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), of which, to this day, it is a mere observer. Celso Amorim, Brazil’s foreign minister at the time and today Lula’s chief foreign policy advisor, always considered this would have been a bridge too far and would have “rattled the cage” too much, both at home and abroad.

Something similar can be said about the decision on the BRI. This decision is very much in keeping with Active Non-Alignment (ANA), the approach that inspires Brazilian foreign policy these days. ANA is about putting one’s own country’s interest front and center and not letting oneself be pressured by the Great Powers. As we argue in our forthcoming book The Non-Aligned World, paradoxically, this very competition among the Great Powers that creates current international tensions is also a source of opportunities for developing nations if they stay squarely in the middle, do not take sides, and are able to play the Great Powers against each other.

ANA is about keeping good relations with the two (or more) competing Great Powers (these days, the United States and China); about diversifying foreign links; as well as about mitigating risks and covering one’s back in a highly uncertain environment in which a mistake can have devastating consequences. This is called hedging, the preferred tactic of ANA. This means not just taking a position in the middle between the Great Powers but also acting in unexpected and seemingly contradictory ways, keeping your options open and others guessing about which your next move will be.

Brazil, which will chair the G20 this year and next year will chair COP30 and the BRICS group, is now a veritable diplomatic hub in world affairs. It must, therefore, be especially careful about how it manages this pole position. President Lula prides himself on his good relations with President Biden, but he also undertook a Ukraine peace initiative last year that did not go down well in Washington. Lula visited Beijing in 2023 but was careful to visit Washington first. Signing on to the BRI would have entailed a needless “rattling of the cage” in a highly fraught international environment. Brazil knows better than that. The substance of its foreign policy has not changed one iota, and the whole episode will soon be yesterday’s news.

Jorge Heine is a research professor at the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University. His book, co-authored with Carlos Fortin and Carlos Ominami, The Non-Aligned World: Striking Out in an Era of Great Power Competition, is forthcoming from Polity Press in April 2025.