By Rebecca Ray

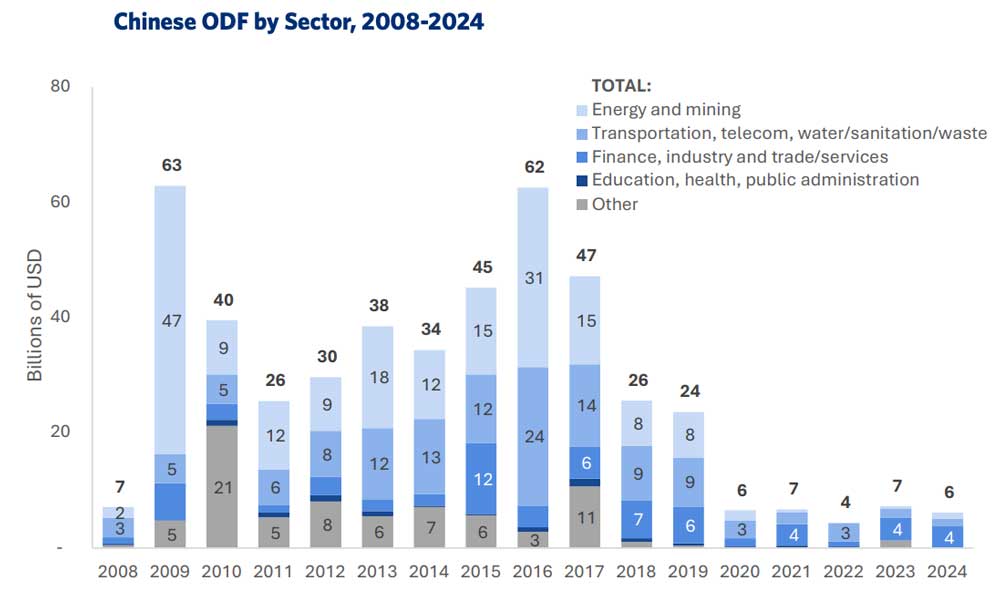

In 2024, China extended $6.1 billion in 20 commitments in public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) loans, according to a new update to the China’s Overseas Development Finance (CODF) Database managed by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center).

This lower level of lending from its development finance institutions (DFIs), the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China, represents a dramatic departure from the early years of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), when Chinese DFI lending frequently surpassed $30 billion in a given year.

Beyond the headline reduction in lending, another trend stands out: over the last five years, Chinese DFIs have made an abrupt pivot in their sectoral focus. From 2008-2019, energy was at the core of their PPG lending, including multi-billion dollar commitments to state-owned energy companies such as Brazil’s Petrobras or to specific energy projects like South Africa’s Kusile power plant.

Development Policy Center, 2025. Note: “Other” includes multi-sector and discretionary loans.

Transportation was the traditional runner-up sector, including high-profile rail projects in Indonesia,Kenya and Malaysia. But from 2020-2024, the top sector has been finance, particularly lending to development finance intermediaries like national development banks (NDBs) and regional development banks (RDBs). Energy lending was down to just 10 percent of the portfolio while finance rose to nearly half: 44 percent of total commitments.

The Risk-Management Advantages of Peer-to-Peer Lending

This new approach to relying on DFI peers bring an important advantage: it shifts the task of project selection and management from Chinese DFIs to local NDBs and RDBs. Under the “small is beautiful” approach, managing many small-scale projects is institutionally burdensome for these large, geographically distant banks.

Furthermore, project selection has long been a complication for Chinese DFIs, which are still developing their environmental and social risk management (ESRM) systems, which other DFIs employ to avoid the suspensions, cancellations and reputational losses that arise when high-risk projects are allowed into a bank’s portfolio.

The Chinese government has taken important initial steps in this direction. The 2021 Green Finance Guidelines (GFGs) of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, now restructured as the National Financial Regulatory Administration (NFRA), advise banks to develop practices that include community consultation and grievance mechanisms—for example, effectively harnessing community experiences to highlight risks before they have a chance to threaten project viability.

However, as of mid-2025, NFRA hasn’t published key performance indicators yet, so banks are still missing the targets that they would need to implement the GFGs. In the meantime, it may be beneficial to continue lending to intermediaries and leave project oversight to them.

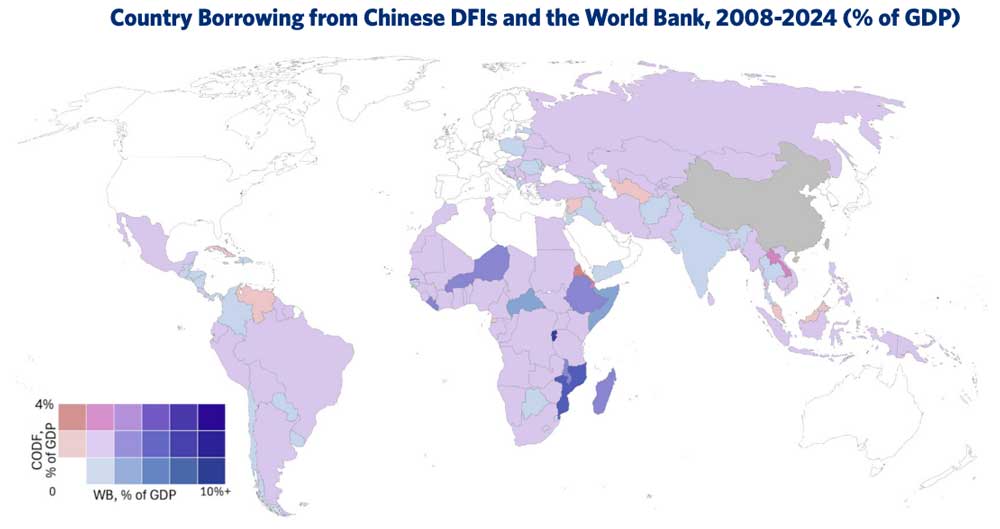

The fact that Chinese DFIs are still building their ESRM frameworks brings risks beyond the banks themselves; it also has serious implications for affected communities and the local environments that support them. Earlier GDP Center research finds that compared to World Bank projects, Chinese DFI-financed projects pose significantly higher risks to biodiversity and Indigenous peoples.

Further research shows that these local environmental and social concerns pose real risks for project viability, with higher-risk projects more likely to face suspensions or cancellations.

Development Policy Center 2025; International Monetary Fund 2025; World Bank 2025. Note: These figures exclude World Bank loans of less than $25 million for comparability with CODF.

These environmental and social risks have not abated over time. The CODF Database tracks projects’ overlaps with three kinds of socially and environmentally sensitive territory: Indigenous Peoples’ lands, national protected areas and potential critical habitats. Over the last five years, the physical projects that are directly financed by Chinese DFIs (rather than being financed through NDBs or RDBs) were more likely to overlap with these territories than during previous time periods.

In fact, from 2020-2024, approximately two-thirds of Chinese DFIs’ direct project finance went to projects that overlapped with at least one of these types of sensitive territory. Thus, from the perspective of Chinese DFIs, and until they have robust ESRM practices, pivoting away from direct project finance and toward partnerships with local DFIs brings obvious advantages for mitigating these risks.

Building a Better Pipeline: The Promise of Project Development Facilities

From a development perspective, however, what matters is not simply which bank finances a project but the selection and design of projects themselves. This is true for the sake of local communities as well as for the sake of the entire planet and the prospects for a global energy transition. China has been vocal about the potential role of the “Green BRI” in advancing global energy transitions. At the 2024 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), China pledged to support new clean energy projects and signed direct development finance deals for solar projects in Namibia and Zambia.

Unfortunately, the Global South – and particularly Africa – is still lacking in project development facilities to build up a pipeline of future green energy or other sustainable development projects. For this type of lending to expand – either directly or through intermediaries – these projects will need to exist on paper.

At the 2023 Belt and Road Forum, China unveiled an initiative to help fill this gap: the Green Investment and Finance Partnership (GIFP). If and when the GIFP begins to function as a project pre-feasibility facility, it may play a crucial function in turning the Green BRI into a bridge for future green development in the Global South.

Given the lack of fully fledged ESRM procedures at Chinese DFIs, and the general dearth of project development facilities for sustainable and low-carbon development projects, it is understandable that Chinese DFIs would pivot away from direct project lending and toward relying on their peer DFIs for project selection and management. In the coming years, if these initiatives grow into their potential, the Green BRI will become a stronger partner in the Global South’s transition toward a sustainable future.

Rebecca Ray is a Senior Academic Researcher at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center). Follow her on X: @BUBeckyRay