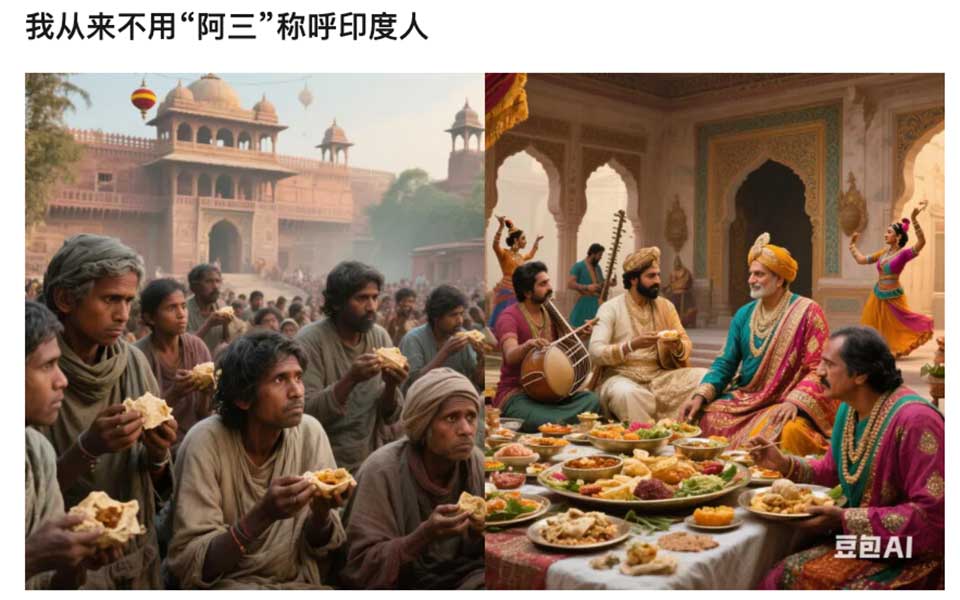

A recent article titled “I Never Call Indians ‘A San’” (《我从来不用“阿三”称呼印度人》) has triggered rare self-reflection on Chinese social media over deep-rooted prejudice toward people from other Asian and Global South countries.

Published by the WeChat account Basic Common Sense (基本常识)—a platform known for science and social commentary—the piece directly challenges the widespread condescension many Chinese express toward India.

The title refers to “A San” (阿三), a slang term historically used in China to mock Indians. Though it literally means “Number Three,” it’s commonly understood as a derogatory label implying someone is backward, subordinate, or laughable.

The article opens by acknowledging the problems often cited about India—its caste system, gender violence, and underdeveloped infrastructure. But it quickly turns the mirror on Chinese attitudes.

“To scorn India is to pay a heavy price for arrogance and ignorance,” the author writes.

It then argues that India’s rising power, thanks to its massive population, influential diaspora, and competitive edge in business and tech, makes such scorn shortsighted.

One key paragraph states:

“Due to high English proficiency and strong ethnic solidarity, the global presence of Indian immigrants is rapidly growing. Their influence in technology, education, and business is expanding. For individual Chinese people, being compared to Indians is inevitable—and unfortunately, Chinese don’t always come out ahead in international perception.”

The article ends with a direct warning: “Indulging in a sense of superiority over Indians is perilous.”

But it’s the reader’s responses that paint the fullest picture—sometimes thoughtful, sometimes defensive.

Discussions like this are rare in China’s highly nationalistic online space, where pride often leaves little room for self-criticism. But this time, a simple refusal to use a slur has opened up a deeper debate—and some are finally listening.

One commenter wrote:

“If 90 out of 100 Chinese people are hostile to Japan, then 99 are prejudiced against India. Most people’s impressions of India are shaped by clueless internet memes…Yuan Nansheng, the former Chinese Consul General in Mumbai, once wrote an article titled ‘The Real India Through the Eyes of a Diplomat (《一个外交官眼中的真实印度》)’ which is relatively credible. After reading it, one gets a sense of a completely different India.”

Another added:

“It’s ironic. Many Chinese feel outraged by Western stereotypes of China—but when it comes to Indians or Southeast Asians, we’re even more arrogant and dismissive.”

Others shared firsthand experiences:

“I work in Singapore, surrounded by Indian engineers. They’re smart and hardworking—just like us. Even on construction sites, most Indian workers aren’t lazy at all. As long as their work is well organized, they perform just fine.”

Some pushed back with caste-based views:

“That’s because they’re not Brahmins or Kshatriyas.”

And others highlighted India’s English advantage:

“Their command of English gives them a real edge. Making fun of their accent is pointless—plenty of Chinese still speak broken English.”

One response downplayed that:

“That’s just a colonial legacy—India was a British colony. It’s not an inherent strength.”

Discussions like this are rare in China’s highly nationalistic online space, where pride often leaves little room for self-criticism. But this time, a simple refusal to use a slur has opened up a deeper debate—and some are finally listening.

Discussions like this are rare in China’s highly nationalistic online space, where pride often leaves little room for self-criticism. But this time, a simple refusal to use a slur has opened up a deeper debate—and some are finally listening.